Travel with Osher!

Spring/Summer 2024

Volume 34, No. 1

Contents

I Just Kissed A Girl Named _ _ _ _ _

By Jim Herrell

In my early adolescence, I aspired to be an architect, despite a total lack of visual imagination and drawing ability. I spent hours sketching plans for the house of my dreams, a circular structure with right-angled rooms, but I couldn’t design a square interior to a circular house that didn’t leave a lot of unusable space.

Many other experiences from those days are stamped in my brain. I remember the day and time certain things occurred, and the weather. I remember with whom I went to a given movie at what theater and where we sat. I remember some conversations verbatim.

I remember the paper route I had during my junior high years, getting up every morning at 3:45 to deliver the Austin American to the front porches of over 100 customers, remembering it all so clearly that two-thirds of a century later I’m sure I still could deliver papers to those porches with 90% accuracy. I remember every girl I dated, not that their number strains my memory banks, and in some cases how many dates we had and what we did on each.

What I can’t remember is the name of the Mexican-American girl I secretly dated in ninth grade. We sat next to each other in classes with alphabetical seating, so maybe her last name was Herrera or Hernandez or Guerra or Gonzalez. What was her first name? Sometimes I think it was an anglicized name, like Janie, but no, that’s the name of a Chicana secretary in a building where I worked as a janitor while in college, a woman at whom I sneaked peeks while pretending to clean around her desk. Or maybe it was Joanna, but she was a college classmate in an American History course, a Latina who once came late to class, weaving between rows to find an empty seat, so alluring that when the young assistant professor stopped gawking and resumed his lecture on late-19th-century political developments, he skipped from Rutherford B. Hayes to the second Grover Cleveland administration.

No, I cannot remember the name of the young lady I saw on the sly the fall of 1956, recalling only the names of other desirable young Mexican-American women, so I will call her Maria.

Although I sat next to Maria in several seventh- and eighth-grade classes, we rarely spoke to each other. Too unliberated from the Texas gringo ethos to talk with Mexicans of either gender, too shy to initiate conversations with pretty girls of any ethnicity, I’d done nothing bolder than admiring her. Late in our eighth-grade year, a substitute teacher in a science class, struggling to maintain discipline, began asking each student to name a favorite song. Elvis, The Platters, Fats Domino, and Little Richard dominated the charts that spring. Not exactly as one with contemporary pop culture, I cited the only song I could think of, “Band of Gold” by Don Cherry, which a few months back reached number five on the charts. The word “square” floated around the room, accompanied by snickering. Even the substitute snickered. I’d never been so embarrassed, but it got worse. “Don’t make fun of him!” Maria suddenly said, her scolding tone modulated by the melodious Spanish tinge to her voice. “Maybe he has better tastes than any of you.” It was possibly the first time she’d ever spoken in class unless directly called upon. It was certainly the most humiliated I’d ever been, first to have demonstrated my squareness, second to have been defended by a girl, who, third, was Mexican.

Although I recall no subsequent significant discourse that semester between me and my protectress, I recall clearly my ever-increasing crush on her.

One fall afternoon early in my ninth-grade year, as my mother, on carpool duty that day, began driving away from the schoolyard curb, Maria walked by. Seeing me in the car, she waved and said, “Hi, Jimmy,” her smile the most beautiful ever offered me before or for several decades thereafter. While my heart pounded and my stomach roiled, my carpool companions gave me a hard time. “Hi, Jeemy,” they said repeatedly, mocking Maria’s accent.

At home, my mother confronted me about the incident. “You’re not thinking about dating her, are you?”

“Uh, no,” said I, who’d thought of nothing else for the last several minutes.

“Good,” she said. “Never date a Mexican!”

Soon after receiving this injunction, I needed to spend time at the main branch of the public library, across the river from our school, to gather information for a term paper. I mentioned this to Maria, off-handedly, like “Aw, man, I’m gunna have to spend a few nights at the dang liberry readin’ up on stuff for this stupid paper. I wunner if anyone else in class’ll be there.” Maria, offhandedly, said she might. We established a routine, meeting at the library after dinner one or two evenings a week, arriving separately by bus, picked up separately by parents a couple of hours later. The first week, we actually worked on our papers, sitting at different tables, smiling occasionally at each other, before strolling in the park across the street, holding hands and sharing a kiss or two. In subsequent weeks, we went straight to the park, but before our parents arrived, we’d enter the library for a few minutes so we could truthfully say we did.

We bonded, felt like soul mates, although those expressions were not then current. We had in common being social outsiders—both of us because we were nerdy honor students, Maria additionally because she was Mexican. Conversation flowed easily between us. We talked about teachers, fellow students, sports, TV shows, movies, and top-40 music, the last of which I’d gotten into with a vengeance following the “Band of Gold” debacle. We talked about career goals. She wanted to be a nurse, and I, the architect wannabe, told her about my struggle to design a circular house. We laughed together at my pathetic sketches, and she helped me think about more realistic career options.

Here’s what we didn’t talk about: Ourselves as a couple, why we didn’t date openly, why at school we only spoke to each other if no one else was nearby, why I took Suzanne to the band hayride. From the beginning, we feared being outed. The social prejudices and taboos of our time and place that necessitated our meeting in secret were powerful, and we would each face serious disapproval were our relationship to become known to family or friends.

Near the end of the fall term, Maria told me her father had accepted a job in another city, so she would leave Austin at the end of the semester. We could think of no way to sustain our romance, no safe intermediaries through whom to keep in touch. On a raw winter evening, we strolled our final stroll, kissed our final kiss, perhaps shed tears, and she was gone, taking her smile and her name with her, leaving me with all that empty space in my dream house.

Back to the Table of Contents

Downright Sacramental

By Randy Barker

Written in the waiting room of Dr. John Charleton August 31, 2023, while he tended to Marie Claire’s feet. This memoir piece draws on memories from several of my own visits, visits during which his father, now deceased, and his mother, still present, were crucial parts of my experience.

Years ago, tending to the feet of a dear friend who was dying, he gave me his card. It was a card that would invite me into a place both patriarchal and matriarchal when my own feet cried “au secours!”

Patriarchal: While waiting for foot care, I enjoyed his father’s fatherly story-telling in an old-fashioned antechamber. The stories came with gestured figures of feet only his hands could configure. In his 90s by then, he was the ancestral prophet to all that would follow inside.

Matriarchal: Presiding over the way-station to all the way in, his mother’s motherly kindness made me ready. Made me ready from the tips of my tough-looking toes to way up where I SAVOR life best…by placing both feet in whirling warm water then toweling off each, on bent knees.

The foot care inside, by their love-begotten son, fulfilled the promises his parents had made outside. If feet could be hallowed, that’s how I could best recount what came next. Each toe, greatest to smallest, became most-favored for a minute or so. Most-favored in how, through clipping then smoothing, it was re-birthed to the nubbin it hid ‘neath its nuisance. The blessings the master ministered to my 10 toes were rites they expected. What made my time in his presence a balm for days to come was his fluent recounting of parable on parable I awakened with whatever I uttered. My “…a crazy small black shaggy dog…” brought his “…a yellow 200-pound scaredy-cat… as far down under the covers as he could get…the minute he heard thunder or saw lightning strike”….and about nine more stories.

I said a balm. That describes best my reward when I brought my feet home from a temple where all that happened seemed downright sacramental.

Back to the Table of Contents

Connections

By Jeanne Marie Randall Wills

Author’s note: When they could no longer live independently, both of my parents moved into my home and eventually into my sister’s home. Together they made a whole person, but after my father passed in 2011, my mother lost the collaborative memory support they provided to one another.

Precious parts of her social graces remained. She nodded to everyone at the table as she caught their eye and verified that each person had something to eat. She would not leave the table if someone was still eating and would say quietly, “I don’t want to leave this person alone at the table.” When someone arrived, she would gently touch their arm and ask, “What can I fix for you to eat?” But she could no longer fix meals.

Most memorable is the way she connected with people, gazing directly into their eyes, smiling and giving nods of acknowledgement even as she gradually forgot names and became less verbal. Her great love of music remained as a strong connection.

Connections

Why Do I Feel This Love?

How strange.

I feel a surge of

Deep visceral love.

Who is this person?

Deep within my brain,

Deep within my womb,

These parts of me respond.

I look intently at the face.

Still I cannot recognize it.

An emotion of soft warmth

envelops me.

Sending Love

Her gaze is curious,

And soothing.

She is calm.

She does not speak,

She does not answer me

with words.

I mirror her interest,

Looking directly into her eyes,

Filling her soul with love.

She looks down and pats the small Bose speaker I place in her lap. The white knitted gloves that bring her comfort keep her small bent fingers warm. I tuck the afghan around her legs, purposely brushing her left ankle as I always do to check her left leg which has been cold to the touch for the last three years now.

Bing Crosby croons to us, followed by Frank Sinatra, Julie Andrews, her favorite Broadway show tunes, classical music, operas, and the popular music of the 40s that she sang to me as I crawled across the floor to be near her beautiful voice so many years ago. She filled our home with music, and I share her own gift to me with her now.

She smiles at me and we reach for one another’s hands at the same time. My mother and I sit together wordlessly. Holding hands, sitting side by side we have no need for words as we float gently along on a wonderful musical journey together on a lazy afternoon.

Back to the Table of Contents

TWO FABLES (Or Follow the Science)

By Fred McCormick

How the Dinosaurs Became Birds: Long ago vast herds of herbivorous dinosaurs roamed the face of the North American continent. They followed the changing seasons in the course of a year. As the omnipotent green spread ever northwards with the advance of spring, the dinosaurs followed in its wake until they reached the edge of the ice. They raised their young during the endless day of an arctic summer while they contentedly cropped the short grasses of the open tundra.

When, eventually, the world around them grew cold and dark, the dinosaurs turned their heads toward the south and headed back to the lands that were never touched by the frost and snow. For countless aeons the dinosaurs kept to this design, following the sun south to north and back again while the earth plunged on through the depths of the blind cosmos. Autumn leaves covered the tracks of the infinite generations that followed unvaryingly this ancient pattern—south to north, north to south.

Then, one day, when the herds emerged from the dark depths of the great northern forest, on the edge of the vast central plain they found their way blocked by gigantic herds of mammals that spread far beyond the horizon, out of sight. These creatures traveled the plain, following the rains, east to west, west to east, and their ceaseless journey crossed that of the dinosaurs. It was a colossal gathering in motion of rutting males, females quietly chewing their cuds, and bleating calves vigorously stretching their young legs. All were covered with thick, soft, brown hair.

The dinosaurs did not know what to do. Their way was blocked. They could not pass through the hairy multitude to continue their timeless habit. Their restlessness grew as the need to complete their instinctive cycle became more and more a desperate priority. Finally, in a last effort of strength and necessity, the dinosaurs backed away from the plain to the very edge of the forest and formed themselves into an orderly phalanx. Suddenly, they charged the herd of disinterested mammals, making an earsplitting thunder in their irresistible surge. It looked as if a horrendous collision was about to occur. But, at the last moment, just before what seemed like an inevitable catastrophe, the dinosaurs took a long, high leap into the sky and mutated themselves into light, streamlined, gaily colored birds who soared like arrows over the mammals and away to the south. To this day the birds continue to follow the seasonal south/north trek of their ancestors. They fly high above the shaggy backs of the usurping mammals, closer to the sun.

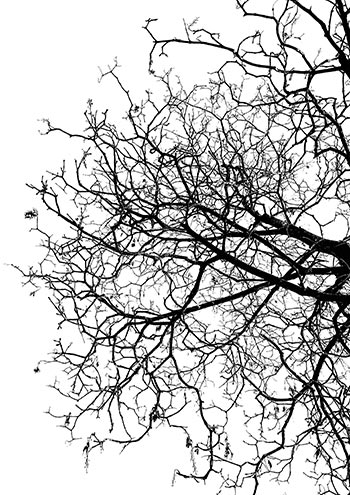

The Last Leaf: After the last blast of chilly wind, a calm had settled over the neighborhood. The grey-brown branches of the old oaks, maples, and elms that lined the quiet streets in front of the houses were suddenly still. The leaf, loosening its firm hold for a brief moment, looked out at the mostly empty canopy divided by neat walks and lawns and thought of all his comrades who had already been swept away on the breeze to the ground below.

“I wonder when my turn will come,” the leaf thought.

It was autumn, the time of year when all leaves lose their deep green color and eventually fall from their trees. The young, bright green leaves were told about autumn in the spring by the workmen in the fibrovascular bundles. They had the good fortune to keep their jobs after the end of the growing season and for many seasons after that, though they slept long and deeply in winter. If, however, a bundle worker was in an annual plant’s system, he shared the misfortune of his leaf companions. Only the potential lives secured in the tiny, dust-like seeds would continue the time-out-of-mind tradition of yearly growth and blossoming that is the fortune of plants.

Yes, the leaf knew about autumn from the beginning; it was always at the back of his mind from the time he peeped out from his bud in early April. But in the rising sunshine and warmth he had put the thought in the back of his mind while he grew and made many friends of other, similar leaves on the branches near him. In the clear, dry air or sudden May shower, autumn seemed very far away as he and his chattering friends went about their business of producing food for all the other workers throughout the body of the tree, from the deep roots to the highest branches. But through the late spring and summer months, deep into September the shadow of autumn inevitably grew larger. Now the time was at hand with all its fierceness and loneliness and death. Most of his friends were gone now, and when each individual whom he had known fluttered helplessly away a part of this leaf went with them.

Just a few moments ago, the companion leaf, who had budded out in full splendor on a cool bright April morning at almost the same time as himself and who had always boasted that he would never let go and would hang on with imperious determination all through the dark winter until spring again came around, had wearily, even voluntarily, let go in the latest rushing gust of wind and had vanished into the street below, lost amongst countless other fellows. No longer deep green, but piebald yellow and red and spotted brown, wilted at the edges, his once-proud friend had accepted and even aided the inevitable.

“Change and decay is so remote in a lost youth,” thought the leaf. “Now ending is a soft breath away, just one rush of wi…”

Back to the Table of Contents

Beauty Box

By Sugie Weiss

My mother drove her 1961 Sunbeam Rapier, aka Beauty Box, with delight until she stopped driving and Beauty Box took up residence in her garage. There she sat for many years, past her prime, surrounded by artifacts of our family, including a standing freezer holding the remains of the tops of wedding cakes and the beautiful body of a Baltimore oriole that had sadly crashed into a window.

My mother drove her 1961 Sunbeam Rapier, aka Beauty Box, with delight until she stopped driving and Beauty Box took up residence in her garage. There she sat for many years, past her prime, surrounded by artifacts of our family, including a standing freezer holding the remains of the tops of wedding cakes and the beautiful body of a Baltimore oriole that had sadly crashed into a window.

Now the story as to how Beauty Box came to be there follows. She was made in Britain and purchased in Rome. She was specially ordered with left-hand drive, as she would be returning to Baltimore following her European tour. Why my mother was in the market to purchase a car on holiday defies my memory.

On July 5, 1961, my mother, her twin sister, her sister’s husband, my first cousin, and I all walked into the light-filled Sunbeam showroom located in the center of Rome. The sun glistened off the British Racing Green exterior of what was to be our Sunbeam Rapier convertible. The interior was notable for its burr walnut veneer surmounted by a padded crash roll and dark green vinyl seats with light-colored piping. Additionally, this was the first model that included a fresh air heater, as part of standard equipment. This feature was highly appreciated as we drove through the cold damp mists of the Scottish Highlands at the end of our trip.

My mother signed the papers and the five of us drove out of the showroom, the start of our European tour. In front of the Hotel Flora in Rome, where we were staying, many admired the car.

Beauty Box was a substantial car, made entirely of steel, which gave her heft along with her glowing exterior. As this was before there was power steering in most cars it often felt as if you were driving a truck.

Our tour began with the drive from Rome through the hill towns of Tuscany. We negotiated the narrow roadways and enjoyed the many sites and tastes of the region. The weather was warm and clear so we usually drove with the convertible top down, taking in the sights, sounds, and fragrances of our surroundings. Beauty Box drew attention as strangers enjoyed engaging us in conversation about similar cars that they owned.

Our time in France was remarkable for the incredible view of Chartres Cathedral as we approached it driving west from Paris. The tall gothic spires rose up suddenly out of the open fields and the view with the top down was awe-inspiring.

Our greatest driving challenge awaited us when Beauty Box disembarked in Dover, having accompanied all of us on the Channel crossing. Immediately we were confronted with driving a left-hand drive car in a country where they drove on the left.

The most memorable incident occurred as we were ascending the narrow mountainous road to Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye. We drove up into the clouds and, suddenly on the steepest ascent, the car stalled and refused to start. The manual choke flooded the engine. Backing down was out of the question. Mercifully with a lurch and a squeak she started up and we reached the castle in time to enjoy a high tea with Dame Flora, head of the clan MacLeod (my uncle was a MacLeod).

By the end of August our trip was almost over. Arrangements were made to have Beauty Box shipped from Southampton to the Port of Baltimore. The rest of us flew back, while Beauty Box enjoyed a leisurely sea voyage of 10 or more days, providing her with time to adjust to life in the States.

Back to the Table of Contents

The Brave Warthog

By Dorothy Lopez

When our family of four took a safari in the Masai Mara in Kenya in 2019, I anticipated observing wildlife in their habitat. Little did I know that we would witness an extraordinary event that seasoned safari spectators may not experience in a lifetime.

The Masai people inhabit land mottled with rocks, trees, and bushes. We arrived at the western part of the country, a natural reserve that teems with elephant, hippo, lion, baboons, cape buffalo, rhino, crocodiles, and more. As soon as we left the plane our safari began. We spotted zebra, giraffe, baboons, elephant, and several more species. As we rode to camp, the horizon appeared endless, exploding in shades of tangerine and sapphire. The contrast with the sage shrubs, grasses, and tan earth provided a magnificent vista. At sunset, as we chatted with our Masai hosts and sipped sundowner cocktails, we watched the sky meld with swathes of crimson and silver plum that deepened to charcoal raisin.

We timed our trip to experience the Great Migration where about two million wildebeest, zebra, and antelope journey in huge herds from Kenya to Tanzania in search of food and water that ebb and flow with the seasons. Each year, about 280,000 animals perish from predators, debilitation, dehydration, and famine during the passage. Often, tourists wait at the river crossings to witness the display. (We caught the end of the massive movement of huge herds crossing the savanna. For me, the last episode I wanted to encounter was a suffering animal or witnessing a kill, but I knew that I probably wouldn’t escape it.)

On the third day of safari, we spotted a cheetah with a bulging chest. Our guide, who drove the area daily, believed that the animal hadn’t eaten recently. He said that a few days earlier, he had seen it kill a zebra and witnessed a pack of hyenas, that must have caught the scent, attack the cheetah. After a fight, the cat slinked away while the hyenas gorged. Our guide engaged us with facts about hyenas: Though they are excellent hunters, it’s not uncommon for a pack of hyenas to send out a scout to detect a kill. When the kill is confirmed, the scout alerts the pack and the hyenas rush to the scene to feast. A spotted hyena can weigh up to 190 pounds and consume 30 pounds in one meal, and they don’t just dine on animals and plants. The Masai people dispose of their dead bodies by placing them outside their encampments of mud huts for the hyenas to drag away and eat.

We watched the cheetah lounge on a mound above a field. Its head perched and swiveled. The animal appeared stoic as it searched. The cat rolled over providing an alternative view of its surroundings but remained hidden from below. A herd of impala had wandered into the pasture and grazed unaware of impending danger. My chest tightened when a few small impala meandered closer to the hill. The cheetah spotted them and rose to a crouch.

Since we were behind the cheetah, our guide started the engine and drove the jeep around to the right side where we could get a better view of the cat and the field of impala. As we waited, about eight jeeps surrounded the animals. Telescopic camera lenses balanced on stands and poked from vehicles. I readied my camera using my 400mm zoom and set it for continuous shooting. My heart quickened, while my stomach grew queasy. However, the knowledge that the cheetah was hungry helped quell my concerns. Moreover, our African safari enabled me to understand the significance of killing for survival, especially when I witnessed the lions feeding their cubs.

A lull hung over the grassland as our anticipation grew. I drew in my breath as a little impala wandered away from the herd to within several yards of the predator. As the fastest animal in the world, a cheetah’s speed can reach 75 mph. To kill their prey, they rip the throat suffocating it. The impala didn’t have a chance, and I dreaded the drama.

We waited, whispered, and watched the impala edge closer to the cat. Unexpectedly, with the precision of an A-10 Warthog fighter jet, a lone warthog crossed the field behind us. On a mission, it trotted down the hill and directed its path toward the grazing impala. It mingled with the impala within yards of the predator. I held my breath. Like a guided missile, the hog charged the hill, storming the cheetah. The cat lunged and outed itself. It appeared that the warthog had purposely flushed the animal out to deflect the attack. The impala bolted and so did the pig. Our ranger voiced surprise that the hog endangered itself against one of its top predators. He added that warthogs are unlikely to become aggressive except with another male of its species.

I sighed and said, “Oh well, it wasn’t meant to be.”

Our daughter said, “Mom, the warthog saved the impala. We bet that’s your favorite animal in the Masai Mara.” Our son readily agreed.

I said, “Warthogs weren’t my favorite until a few minutes ago, but now I suddenly have a fondness for them.”

The guide started the engine, and we followed the cheetah across the terrain. It perched on another knoll that overlooked a field occupied by a pack of hyenas. A hyena scout trotted across the meadow and up the slope and stood in front of the cheetah. The cat hissed and rushed the animal. The scout retreated. This time, the hyenas’ and cheetah’s luck had run out. Lacking a kill, they went without.

Back to the Table of Contents

The Favorite

By Barbara Pallas

My mother says that I am his favorite, that I always have been and that I always will be. He has two other daughters and a son; but Mom says I am the special one!

My mother says that I am his favorite, that I always have been and that I always will be. He has two other daughters and a son; but Mom says I am the special one!

I did not feel special when I was growing up. I was the oldest of four children and I was expected to help with my siblings, but my days included doing as little as possible, refusing to do what I was asked to do and just making mom’s life miserable. And my bad behaviors continued even after he came home from work. He would tell me that I “was” going to do the dishes and I would say that I “was not”—and the battle began! I was defiant and when I made up my mind not to do something, even a good paddling across my backside could not make me change my mind or say I was sorry. My bottom surely did not feel special when I was growing up.

He was not perfect either. Sometimes he became “lost” on his way home from Bethlehem Steel where he worked as a brakeman on the railroad. He was not a man with the willpower necessary to turn down a free beer from friends and he knew every tavern on his drive home. Often, he lost track of the time and arrived home three or four hours after his shift ended leaving my mother wondering whether he had been in an accident or was lying on the side of the road. We had only one car so my mother would call the taverns to see if he had been there. I watched her eyes fill with tears and I hated him for how he made her feel. He was a different man when he drank—a nasty, mean person who slurred his speech as he stumbled into the house and collapsed on the sofa. This was not the same man who read stories to me, took me to Oriole games, taught me how to hit a baseball, catch high flies in the field behind our house, and who hugged me when I needed hugging. The man I loved taught me how to fly a kite, how to ride a bicycle, and allowed me to stay up late during the summertime to watch old black-and-white movies while sitting next to him on our sofa, sipping Coca Cola and eating Utz potato chips.

He showed extreme patience while teaching me how to drive a car. “Let the clutch out slowly and give it a little more gas,” he said as we jerked down the road. “Drop it into second as you go around the corners.” He never raised his voice to me, even when my braking skills almost put him through the windshield. Mom says he was not as tolerant when he taught her to drive.

Since there were six of us in the family, money, or the lack of it, was often a problem and caused arguments between my mother and him. His job paid well but raising four children was expensive and he was often laid off because the railroad moved iron and steel at the mill and when the steelworkers walked off the job, there was no product to move, and he was laid off too. He would then take on odd jobs to support his family. No work was beneath him, and he once worked on a garbage truck and brought home the “treasures” that other people had thrown away. I will never forget the year that he and a friend purchased a truckload of cut Christmas trees to sell before the holidays. He stood on a busy corner in the bitter cold selling trees. He allowed me to help him, and I sold a scrawny little tree to a man for five dollars. I was proud of my achievement, and he told everyone that I was his best salesman. I had a good teacher.

He came from a family that included his mother and father and four siblings. His father was a Merchant Marine who arrived in the US on a ship from Germany in 1917 on the day that World War I broke out in Europe and was told to learn English and find a job because he could not go back home. As the oldest son, he was expected to work as soon as he was able, and he quickly learned from his father that life was not meant to be easy, but you accepted the hand you were dealt and always did your best. He grew up during the depression learning how to fix what was broken and make use of whatever was at hand. He learned how to fix cars by helping a neighbor fix his vehicle. He learned how to lay brick by working with a friend who owned a masonry business. Like many men from that generation, he “knew a little about a lot.”

As I entered my teens and started dating, he was a trusting and lenient man. I had a midnight curfew, but he was never angry and upset when I arrived home late. He was interested in the boys that I dated and often started a conversation with them about sports just as we walked out the door. I would “roll my eyes,” and he would keep talking and smile.

The day before I was married, I was packing for my honeymoon when he came up the stairs as I was heading down. We looked at each other and I began to cry as he put his arms around me and told me that he loved me. That was the first time that I realized that I might be special to him. The next day, when he walked me down the aisle and turned me over to my new husband, I detected a tear in his eye.

The following years saw him become the “fixer upper.” If a repair was needed in my house, he appeared with his toolboxes. It could be a washer in a leaky faucet, a car repair, or a bad circuit breaker—he fixed them all with ease and would then stay for dinner. As my children came along, he took on the new role of grandfather. With his prompting, the granddaughters learned early to say Pop-Pop. My mom said that he spoiled them in the same way that he had spoiled me.

After 13 years of marriage and two children, my life changed forever when my husband died suddenly. It was an unimaginable shock to me and to our family. The person I wanted more than anyone else after my husband’s death, was my dad. I knew that he would hold me tight and tell me everything was going to be all right, just like he had done when I was a child. My dad influenced me more than any other person in my life. He was my teacher and my confidante. He was the man I admired most and the person who always looked out for me.

I realize now that the closeness I feel to my dad is due to how he treated me when I was growing up. He always had time for me and even when I was smart-mouthed and defiant, he took the time to correct me. He disciplined me often but always with love, compassion, and an explanation of what I had done wrong. As I reflect on those years, I realize that my antics were to get attention and I achieved that goal, though not in the way that I intended at the time.

My mom still says that I am his favorite and there is truth in what she says. I am his first-born child and his oldest daughter. Personality wise, I am more like him than I am like my mother. I have his fair skin and his blue eyes. I believe that he sees himself in me; and I recognize now just how much of me is him—and that makes me feel very special!

Back to the Table of Contents

The Generations

By Maurine Beasley

I was born into one generation, obviously, but I never felt a part of it because my orientation was to a previous one, so at this point I think my life could symbolize all of the 20th century with a sprinkling of the 19th added in. Nothing perhaps points this out more than my childhood homes. I grew up in houses in Sedalia, Missouri, that might have served as settings for Eugene O’Neill’s plays. They embraced mysteries only dimly spoken of in my presence, fears of family secrets aired in public, evidence of faded Victorian gentility and a general sense of dilapidation. Fortunately for me, they stood in the “right” part of town where the “better people” lived, quite distant from the small frame houses inhabited by railroad workers in East Sedalia and the impoverished African Americans who lived across the railroad tracks from the White population.

I was born into one generation, obviously, but I never felt a part of it because my orientation was to a previous one, so at this point I think my life could symbolize all of the 20th century with a sprinkling of the 19th added in. Nothing perhaps points this out more than my childhood homes. I grew up in houses in Sedalia, Missouri, that might have served as settings for Eugene O’Neill’s plays. They embraced mysteries only dimly spoken of in my presence, fears of family secrets aired in public, evidence of faded Victorian gentility and a general sense of dilapidation. Fortunately for me, they stood in the “right” part of town where the “better people” lived, quite distant from the small frame houses inhabited by railroad workers in East Sedalia and the impoverished African Americans who lived across the railroad tracks from the White population.

My actual address, 1000 South Vermont, marked a big house with a wrap-around porch on a corner lot. It looked somewhat imposing, with columns and a stained-glass window in the hall above broad steps. But, it had a dirty look. My father, in an effort to avoid the expense of frequent painting, had covered it with grey asbestos shingles. Curiously, while it had both a large parlor and living room plus a dining room and kitchen downstairs, it had only two finished bedrooms upstairs. A third bedroom, unlike the rest of the house with its hardwood floors, had what appeared to be a wooden base for the flooring that was never installed. Consequently, you had to watch out for splinters.

As I learned growing up, you also had to be careful of raising the specter of a ghost named Lucille, my father’s first wife. It was hard not to be aware of her because her name was in the books that lined the glass-fronted bookcase in the living room. My parents long since had stopped reading those books, but I would thumb through them occasionally. I wondered about Lucille, who supposedly was beautiful, kind, and cultivated, and whose house this had been. She presumably was a paragon of a virtuous wife when she and my father were married in 1916.

Years later I discovered that the cut velvet sofa and armchair in the parlor, along with the mahogany bedstead and dresser in the front bedroom, had been her wedding presents, along with the prized sterling silver in the dining room with its round oak table. Nobody actually told me about Lucille, but I overheard snippets of conversation that started “Lucille would” or “Lucille wouldn’t,” etc. She maintained a presence in the house, not a hostile one but not a pleasant one either. She had died too young in 1927, just after the adoption of a baby she was said to adore. To think of Lucille made me aware of death at an early age.

Today we would say quite openly that Lucile died of cancer—at least this is what my father told me years later—but in the 1920s this was a hush-hush subject. I heard bits of gossip that she died after a large lump was discovered in her abdomen. Some busybodies speculated she died as a result of a pregnancy gone awry and somehow blamed my father, who was devastated by Lucille’s death. He suffered a nervous breakdown that he never really recovered from, even after he married my mother in 1933. She was a well-educated schoolteacher who expected children to achieve. She did not like references to Lucille, with whom some relatives compared her unfavorably.

My mother did not get along with Lucille’s baby, who became my half-sister, and insisted on breaking the barriers surrounding nice middle-class girls in the first half of the 20th century. She smoked, drank, hated to go to the Methodist Church as expected, and went out with the kind of boy who veered into the “white trash” label. You might know that she was consigned to the bedroom with the unfinished floor, while I slept in an alcove off the master bedroom. She was more or less thrown out of the house when she was sent to a church-related college where she was expelled for staying out all night with a young man. (By the way she never got herself in hand and died of lung disease in 1997 after smoking four packs of cigarettes a day for years.)

When she began her rebellious behavior, not terrible at the start by the standards of today’s generation, both my parents were shocked. My father tried to take her side somewhat in arguments with my mother, who sought to punish her harshly and intimated that she had “bad blood” because she had been adopted. This led to further stress in their marriage. My sister consulted a fortune teller who led her to believe he was her biological father, although I am sure that was not true. Before he died in 1965, he told me she came from a foundling home in St. Louis and that Lucille had looked angelic when she stepped off the train in Sedalia with her new daughter. Why my father didn’t go with her to get the baby I will never know.

But I do know growing up in Lucille’s house made me very aware of generational differences. Visiting my grandmothers’ homes—well, I shouldn’t say visiting because I almost lived there—gave me an acute sense of spirits besides Lucille’s. Both of them represented the past, an era when the residents had enjoyed better days than those now at hand. I grew up at the end of the line, so to speak, the only child of an aging father and his younger—but not all that much younger—wife, the only grandchild of one couple long past their vibrant years and the youngest grandchild of an aged woman whose forceful personality had collapsed when she broke her hip.

My mother had been an only child who remained tied to her parents, to my father’s regret. When I read her diary after her death, most of the entries, all brief, were about taking the baby (me) and going to her parents’ house because they weren’t well. I think she wanted to escape from Lucille’s house.

I remember my grandparents as doing very little except sitting near a small radio. They lived in a square two-story frame house that needed paint. The upstairs was closed off, to save on heat, I suppose, but also neither grandfather nor grandmother could climb the stairs to the second floor. I was not allowed there. Perhaps it remained the province of the ghost of Aunt Minnie, who I overheard mother say, had died in the bathtub there. No one ever told me what brought on her death, but I heard references to “poor Minnie.” Possibly her spirit lingered on with those of the lively young women who once had rented rooms there to boost the family income.

Occasionally grandfather, who I called “grandge,” would walk to town six blocks away to sit with other old men on the bench outside the County courthouse and smoke a pipe. Over six feet tall, he still cut something of a figure with his cane tap, tap, tapping on the old brick sidewalk.

He owned a 100-acre farm outside of town that provided the little money they lived on. Occasionally he would talk about crops, or the tenant with a large number of ill-clothed children, who lived in a run-down house without electricity or running water. He and his family were not considered good enough to live in the modern farmhouse my grandparents had built when farm prices were high in the World War I era, so it sat vacant. The tenant represented “poor white trash,” although no one used that term and the tenant always was called “Mr.” Grandge and “Dot” appeared animated only by the mention of Longwood, the village near their farm. As a young man “Grandge” had raced horses, gone to singing school, belonged to a lodge and been a dashing gay blade. He was one of 11 children of a kindly bricklayer who ran a “blind pig,” the name for a bootleg after-hours drinking establishment. He was known for keeping the inebriated in his home until they sobered up enough to leave safely.

Since my grandparents did little, they expected little of me, which was fine with me. My mother left me with them for hours on end. I took naps with my grandmother, who wheezed a lot as she put her arms around me. We slept on an old iron bedstead that had been put up in what had been the dining room. I called her “Dot.” She smiled a lot and was very sweet but said almost nothing. Once she did call me to “come look at this.” It was a $10 bill. “You don’t see many of these,” she said. And I am sure that in her lifetime she had not seen many. She must have worn herself out working on the farm.

No one worried about providing educational books for me, or even toys, although once Grandge walked to town about six blocks away and bought a red ball for me. I think it cost a dime, but that seems too little even for the late 1930s and early 1940s. I loved that ball and must have bounced it on the dirty porch floor. I didn’t have playmates and entertained myself with old Sears Roebuck catalogues from the 1920s that mother brought down from upstairs.

The kitchen had an actual ice box and a wooden cookstove with primitive gas burners. An ice man came and thrust in 10 pounds of ice from time to time. There was no downstairs bathroom and my grandparents used slop jars throwing the contents down the kitchen drain, a highly unsanitary operation. My parents installed a downstairs toilet to put a stop to that.

Was I deprived? Absolutely not. What I remember most is that I was loved. My grandparents accepted me, just as I was. I didn’t have to learn anything, do anything (except not make any particular trouble) but just exist. Maybe all children should be so lucky.

Back to the Table of Contents

The Joke’s On Me

By Jerry Mulvenna

In 1966, I was employed by IBM as a computer programmer. My office was a large open space which I shared with eight or nine other IBM programmers who were working on the same project. We were all in our mid-20s and we had plenty of outside interests in common to discuss in addition to project-related matters. One of these common interests was the stock market. The fact that we were unsophisticated, novice investors didn’t stop us from having strongly held opinions on the stock market and on the stocks that we owned and from wanting to keep track of how the stock market and our stocks were performing.

The 1960s were the dark ages of computer technology. Not only was there no iPhone, there was no Internet. In Washington, however, there was one brokerage company that provided a recording which was updated several times a day and which provided information about the stock market and stocks that had large movements up and down on that day. Their line was frequently busy so when one of us called and got access to the recording, that person would inform others so that they could pick up their phone if they wanted to listen to the report.

When one day, I heard my colleague, John, tell others about his great expectations for the 75 shares of Crescent Corporation which he owned, I had a sudden epiphany. All the ingredients were in place for me to play the perfect practical joke and John was to be the mark*.

I had recently acquired a piece of 1960s high-end consumer technology—a tape recorder. I now found a use for it. My plan was simple—write and record fake stock reports and then substitute them for the stock reports provided by the stock brokerage company. One Tuesday night, I wrote the scripts and one of my roommates who worked on a lower floor of the same building recorded two fake stock market reports. The first report stated that Crescent Corporation had dropped three points because the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was investigating irregularities in the trading of the stock. The second report stated that the stock had dropped another point and that Crescent Corporation declined comment until the president of Crescent Corporation returned from his Brazilian vacation. When we would play the joke, instead of calling the stock brokerage recording, I would call my roommate who would have my tape recorder with him and he would play the first recording the first time I called and the second recording the next time I called. We had to wait until Friday to play the joke because it would be the first time that both of us and the mark would be together in the same building.

On Friday, everything went as planned. Everybody in the room, except John, was in on the joke. We thought that the second report with the Brazilian reference would give the game away but John believed every word of it. We then went into overdrive over lunchtime, writing and recording a third fake report. The third report was so outrageous that I thought that John would burst out laughing when he heard it. The third report said: “Trading was halted in Crescent Corporation when word reached Wall Street that the president of Crescent Corporation committed suicide in Brazil.” And then the kicker. “When trading was halted, all but 75 shares had traded hands.” I still remember John’s response when he heard this. He said: “75 shares, I own 75 shares. Why didn’t they mention my name?” Before I could explain or calm him down, he then abruptly left the room.

He returned about a half hour later with a copy of the Washington Post under his arm and opened it to the financial section. After a few minutes, trying to refrain from snickering, I asked him: “Have you found anything?” He replied “Yes, it’s here but I don’t understand.” I was startled. I said:” What’s there? What don’t you understand?” He said he didn’t understand how Crescent Corporation stock could have dropped that day because the Washington Post reported that the SEC said that trading of Crescent Corporation would be halted on Friday because it was investigating some irregularities in the company. Stunned and dumbfounded, I carefully read the article because I thought that he might be playing a joke on me. He wasn’t.

I then took the Washington Post article and went down to my roommate’s office. He was at his desk with my tape recorder sitting in front of him. Without comment, I showed him the article. He read it and then looked up at me and said, “Jerry, you are carrying this practical joke too far.”

*mark—The term for someone who can easily be taken advantage of originated with carnival workers (carnies) who ran games of chance at the 1893 World’s Exposition in Chicago. After the carnie found a victim and before sending him away with a cheap prize, the carnie would slap him on the back with a dust-covered hand, marking him as a sucker for other carnies on the midway.

Back to the Table of Contents

Father Van Breda’s Lesson

By Sean McCarthy

In August 1968 before my last year of college I made my first trip to Europe. I took a student charter flight to Paris, sleeping fitfully overnight in a coach seat by a window. I awoke around seven to cloudy morning light. We were flying low over small houses with red tile roofs, a style I had never seen before. I was so excited to be landing in France, I might as well have been Charles Lindberg. After some exploring in Paris, on the coast near Bordeaux, and then in Nice, I met a college friend in Rome. We had time to see a few sights, before we set out by train to Lucerne, Switzerland, on our way to London.

I had decided to detour after Lucerne and travel on my own to Belgium to visit Father Herman Leo Van Breda, a friend of my late father. I had met Van Breda when I was eight years old. My father was a professor of philosophy at the University of Pittsburgh and had invited him to dinner at our small apartment. Van Breda was a Franciscan priest with a PhD in philosophy from Louvain, doing post-doctoral studies at Pitt. My parents befriended him the year he spent in Pittsburgh in 1955–56, and he visited us a few times. After my father died in 1959 I briefly met Van Breda two other times, when he visited the U.S.

Father Van Breda was a handsome, smiling middle-aged man with bushy eyebrows and a twinkle in his eyes, who loved talking, drinking wine, smoking cigarettes, and laughing with my parents. They loved spending evenings with him in our tiny apartment.

My mother had told me fascinating things about Van Breda. He had written his PhD thesis on Edmund Husserl, a German Jewish philosopher who invented a branch of philosophy called “phenomenology.” In 1933 the Nazis had expelled Husserl from the university at Freiburg, Germany, but he died of natural causes in 1938, before the Nazis began their mass killings of Jews. In the short time before World War II erupted, Van Breda had smuggled Husserl’s Jewish widow out of Germany to hide her in Belgium for the entire war. He also smuggled Husserl’s priceless philosophical notes into Belgium and away from certain destruction by the Nazis. In addition, Van Breda had hidden about a dozen Jewish people around Louvain during the war. After the war he founded the “Archives Husserl” where Van Breda was methodically transcribing and publishing the notes he had saved.

A clueless 21-year-old, I didn’t write ahead to tell Van Breda I was coming. Early one grey September day I showed up at his office at the University of Louvain. Entering a dark Gothic building I opened an imposing wood door into a large white-walled room with a few desks and many shelves lined with papers. I asked for Father Van Breda. The secretary disappeared behind some shelves. A few seconds later Van Breda appeared: “You are Professor McCarthy’s son?” He was busy, but most gracious.

After winding up his business that morning, Van Breda spent the afternoon showing me the Archives and a few churches and monasteries in and near Louvain. He volunteered how the people in Belgium had survived the German occupation.

Van Breda said the Belgians were like the Czechs who had just been invaded by the Russians two weeks before: “We didn’t resist. We played dumb. After each air raid, we swept up and replaced the broken glass.” He said when the Germans invaded Holland, the Dutch had gotten mad and retaliated. “It was very hard for them.” I had heard about the Germans shooting many people in reprisal for any resistance.

Van Breda showed me the monastery where he had lived during the war. He had crammed the thousands of pages of Husserl’s notes into his small “cell” there. The Germans never searched the monastery.

We visited a church. It had been bombed during the war, and a beautiful porcelain Madonna had been shattered into hundreds of pieces. Van Breda proudly showed me how the parishioners had painstakingly reassembled it.

That afternoon Van Breda’s German graduate assistant drove us in his VW bug through miles of farmland to the town of Mechelen. Its central church had been built in the Middle Ages and had a steeple that ended abruptly about 150 feet up. When the steeple had started to sway, the town stopped trying to build the tallest church in the area.

Had we come all this way to see an unfinished church? Then Van Breda pointed to Mechelen’s town square with centuries-old stone townhouses facing it. “Over there in the attic of that house, I hid the Steins.”

Van Breda told me that one afternoon he had come to visit this young Jewish couple, and they were visibly upset. He asked them what was the matter. “Do you have enough to eat? Are you getting tired of being cooped up? Please tell me. We can handle any problem.” At last Monsieur Stein confessed: “Madame is pregnant.” Van Breda was stunned. He had no idea what to do, but he didn’t let on. “Don’t worry. We can handle anything,” he told them.

After some pondering, Van Breda approached the Mother Superior of a local hospital. She agreed to have Madame Stein admitted under an assumed name. Madame delivered a healthy baby, but Van Breda was the new mother’s only visitor. “The sisters at the hospital were whispering: ‘Here is a mother with no father who visits, only this Father.’” Van Breda grinned. He loved their thinking he might be the child’s father.

As we toured that day, Van Breda explained how he had hidden so many people without them being discovered. First, he told only one other person where he had hidden each Jewish person. If Van Breda were arrested, he told each confidant to move immediately the person in hiding. If he were caught, Van Breda expected to be tortured and to reveal their hiding places. “I am just a man.” Second, whenever the Gestapo was “on the move,” he got a “sign” to lay low. Incredibly the warnings came from the German military commander at Louvain. After August 1944, that German officer disappeared. I said nothing, but I have always suspected that German commander was implicated in the military’s attempt to assassinate Hitler that summer.

That evening Van Breda, his assistant, and I dined at a restaurant with linen table cloths and formally dressed waiters. My new friends encouraged me to eat a delicacy on the menu whose French name meant nothing to me. The head waiter produced a printed listing of menu items in four languages, including English. My suggested entree was “sweet breads”. I had no idea what those were. However, I couldn’t be a fussy guest. The sweetbreads arrived covered in cream sauce. They didn’t taste bad, but I suspected I was eating the lungs or brains of a cow.

After dinner, we drove to a bar elsewhere in the countryside. It was pitch black and cool outside, but the glass-enclosed patio was warm and glowing. The three of us sat around a table speaking French, our only common language.

Van Breda told a lengthy joke from the war about the hopes of an expectant German mother who wanted to please the Fuehrer. Each turn of this epic began with: “There were two possibilities.” In each case the “better” possibility for the mother (e.g., she bears a boy, not a girl, who grows up to be a soldier, not a sailor, the soldier is sent to the Eastern, not Western front, dies a hero, is buried in an unmarked grave, is ground into pulp for paper, and finally winds up as toilet paper for the Fuehrer) did not sound good to an objective listener. However, each increasingly awful outcome of the “two possibilities” supposedly glorified the Fuehrer in the eyes of the German mother, much to the Belgians’ delight. I’m not sure if our German tablemate enjoyed the joke. He gamely accepted this jab at his countrymen, much as I put on a good face eating the sweetbreads.

That day Van Breda taught me to say “Thank you” in Flemish. He helped me remember by pointing out that the Flemish “Thank you” sounded like an off-color reference to testicles in French (“Ton Cue”). He cackled at the pun. Departing my hotel the next morning, I used my newly learned Flemish to say “Thank you” to the portly, middle-aged chamber maid. She brightened, but was disappointed, when I couldn’t understand her answer.

As I left, Van Breda gave me a copy of the proceedings of a conference on Husserl. Van Breda had written a chapter which translates as: “The Rescue of the Husserlian Heritage”. It tells the story of how he and his Belgian collaborators had managed to smuggle Husserl’s widow and her dead husband’s papers out of Germany and into hiding.

On that September day Father Van Breda had told me a little of that story. It has lessons about good and evil, courage, and selfless sacrifice for others without regard to religion or nationality. Like my father, Van Breda loved to teach as well as to learn. That day I was his pupil.

Back to the Table of Contents

GIBNUT – The Royal Rat

By Sam Dowding

“Da givnut!” This was his response to my sotto voce question “what kind of meat is this, Philip? It doesn’t look like chicken.” My wife had just commented to me that this was the best tasting chicken she had ever eaten, and I had pointed out to her that the bones were different from a chicken’s. The meat had been stewed in a caramel and tomato base and had taken on the color of the sauce, which I knew was quite unlikely with chicken.

My wife and kids had arrived in Belize only one week before, and other than a single foray to Brodies and Ro-mac’s, the two largest supermarkets in downtown Belize City, had not left our temporary housing in the King’s Park neighborhood. It was therefore with glee that we accepted Philip’s invitation for an out-of-town trip to his Belizean wife’s ancestral home: “Come wid me Sunday. Mi di guh da Gales Pint fi bring Joy an dem gyal pickney home.” We embarked in Haulover Creek, which divided north and south Belize City, onto a speedboat similar to those used for sport fishing. The captain gently glided under the Swing Bridge and motored into the Caribbean Sea on our anticipated 45-minute journey.

Our first travel on such an elegant watercraft nearly turned out to be our last. It was two and a half hours later that we arrived in the calm lagoon where the idyllic peninsular community of Gales Point was situated in rural Belize district. In the interim, we had survived a torrential rainstorm, engine failure. and violent waves that threatened to overturn our stalled speedboat.

Soaking wet but joyful to finally disembark alive and well, we were then treated by our host to rural Belizean hospitality that included a sumptuous meal including the ‘givnut’ that we were enjoying.

Philip’s response was one of my first experiences of the many ways that the “creole” lingua franca spoken in Belize differed from the patois and other Caribbean dialects with which I was familiar. On the radio, Belize was then touted as the “Caribbean Beat in the Heart of Central America,” but outside of shared British colonialism and its social sequelae, there was little else that Belize had in common with the rest of the English-speaking Caribbean. Personally, I found it odd that baseball was more popular than cricket in Belize. “Nutten ‘tall nah guh suh wheh me come from!”

Luckily for me, Philip, whom I had met several months prior during my first trip to this unique country, was originally Guyanese and he explained that “givnut”—properly “gibnut”—was the local name for the paca, a ground-dwelling herbivore native to the forests of Central and South America. While scientifically classified as a rodent, the adult paca’s 20- to 30-pound weight, chestnut brown pelt with 3 to 5 lighter stripes and spots, plus its short, tufted tail, all suggest a relationship closer to the deer fawn than to the familiar urban rodent.

In August 1985, I was not acquainted with either term—gibnut or paca—thus it was lucky for me that Philip could clarify that this was the same animal that Guyanese call “labba.” Guyanese have enshrined labba into our food lore with the mantra that “if you eat labba and drink creek wata, you bound to come back to Guyana!” In my native land, folks who grew up with their main protein sources comprising what had been caught in the rivers, creeks, forests, savannas, and back-dams, have often expressed a conviction that labba is the sweetest of all the wild or game meats that we ate. Such a confession, one which I readily volunteer uninhibitedly, was more readily divulged when lubricated by local brown rum of questionable vintage.

Belizeans evidently agreed with the Guyanese sentiments regarding the paca. They consider the meat to be so prized that it was even included on the menu for the official visit by Queen Elizabeth II in October 1985. That the queen was served gibnut caused quite a stir in the British scandal rags. One headline famously read “The Queen eats rat!”

Later that same month, my then 15-year-old British nephew attempted to chastise me on the phone, asking in a haughty clipped English accent “why did you feed the queen a rat?” Of course, it wasn’t me, but the Belizean government who had entertained the queen at that soirée where gibnut was served. But that did not matter to him. Since I was living there at the time, I was in his eyes just as guilty. “It was a rodent, Andre. A rat is a rodent, and gibnut is a rodent, but a gibnut is not a rat!” was my churlish retort.

The queen reportedly did at least taste the gibnut dish that she was served. The British press furor consequently led many Belizean restaurants to add “Royal Rat” to their menus, a highly recommended dish that intrepid visitors and local connoisseurs can still enjoy to this day!

Back to the Table of Contents