Spring/Summer 2021

Volume 31, Edition 1

Contents

Thank You, Buffalmacco

By Nora Hamerman

No classic of world literature has ever seemed more relevant than Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a “frame tale” about ten young Florentine aristocrats who “socially distance” from the Black Death of 1348 to their country villas and pass the time by telling one another 100 stories ranging from the erotic to the tragic, full of slapstick humor and, occasionally, philosophical wit. Boccaccio devotes no fewer than seven of the 100 “novelle” to a gaggle of Florentine fresco painters who seem to have plenty of time for mischief. The group’s chief prankster, Buffalmacco, carries out elaborate practical jokes on their slow-witted and greedy colleague Calandrino, as well as on one Doctor Simone, with a prestigious medical degree whom the artists deem to be an incompetent fraud.

Often the practical jokes seem over the top, even cruel, but they fit into a picture of Boccaccio lampooning class hierarchies and pretension during the social upheaval that ensued from a pandemic that killed at least a third of Europe’s population.

In one story, Buffalmacco and company convince Calandrino that he is pregnant. The gullible artist is terrified that he will have to undergo the pain of childbirth (one of Boccaccio’s many hints that he thought women are the stronger sex). Calandrino’s friends bring in their previous victim, Dr. Simone, to prescribe an abortifacient potion for which Calandrino has to shell out a tidy sum of cash.

Until recently I assumed that these characters with their funny names were pure inventions by Boccaccio, but that he must have been acquainted with the art world of early 14th century Florence, where he spent his childhood and returned in 1341. Side by side with a world-renowned artist like Giotto, there labored hundreds of others who frescoed the villas and convents, the palaces and parish churches of Tuscany. Their work has mostly disappeared, but where it survives there is seldom a name. It included secular subjects which have tended to vanish more than religious decorations (Boccaccio refers to a Battle of Cats and Mice that one of Buffalmacco’s fellow pranksters, “Bruno,” was painting in a local palace.)

But thanks to the Internet, I found out that there really was a Buffalmacco, first name Buonamico, working in Tuscany in the early 14th century. We don’t know if he was a practical joker. Buffalmacco’s recorded works have all vanished, but scholars are convinced, based on documentary evidence, that Buffalmacco and his assistants carried out the largest cycle of murals in all of Italy: the famous The Triumph of Death frescoes in the Camposanto in Pisa, painted around 1438–40, 10 years before Boccaccio wrote The Decameron.

Pisa is famous for its Leaning Tower, but the adjacent Camposanto (cemetery), a treasury of ancient sculpture and medieval frescoes was long more admired. Artists who hoped to emulate ancient Greece and Rome flocked to the Camposanto. Renaissance sculptors found inspiration there to mutate classical myths into Christian imagery.

Tragedy struck in 1943. A stray Allied bomb struck the lead roof of the Camposanto directly, setting off a fire that blazed for days. Much was beyond repair, but some of the medieval paintings, including Buffalmacco’s The Triumph of Death, survived in ruinous condition.

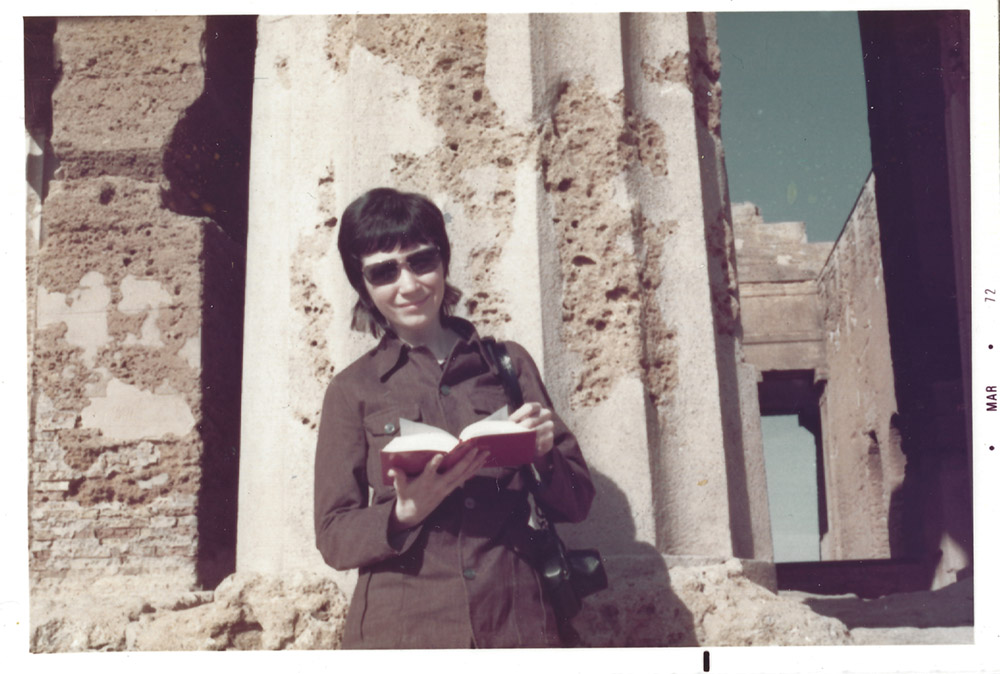

Among those active in the decades-long labor of love that has gone into repairing the Camposanto frescoes were two art conservators, Donatella Zari, a native of Pisa, and her husband Carlo Giantomassi. I knew them when we were all in our twenties and frequented the trattoria “Da Mario” near the Central Institute of Restoration in Rome. It was a modest eatery where local artisans brought their sandwiches and ordered wine in a front room. The back room was the haven of the art conservation community. The owner, the always-worried-looking Mario Mase, waited on tables with his reluctant teenage son and supervised the kitchen where his wife and mother stirred the pasta.

The food was simple (no menu, you just asked Mario what there was and made sure not to miss seasonal specialties like Asparagi alla Bismarck). The clientele included a Carabiniere captain from a nearby station. There was art photographer and inventor Franco Rigamonti, a self-effacing genius who designed spring-expanding aluminum stretchers for Caravaggio’s most famous paintings in a damp church in Rome so that the canvases could “breathe” with the changes in humidity. (Rigamonti’s photographic archive is now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.) There was Luciano Maranzi, a specialist in frescoes. In 1967 Maranzi was flown by UNESCO to Sri Lanka to rescue the frescoes of the ancient Sigiriya Damsels that had been defaced by vandals, and in the process discovered some long-hidden frescoes. There was a young scholar from Finland, Jukka Jokilehto, who later gained worldwide respect for the conservation of historic buildings. A Florentine paintings restorer, Sergio Benedetti, married an Irish girl and became the chief of paintings conservation at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, wherein 1989 he won international acclaim for rediscovering a Caravaggio painting that had been lost for more than two centuries.

Art historians who knew about Mario’s trattoria came in and out, from Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. I have snapshots in a shoebox of several of them standing at the Renaissance fountain on the Piazza Madonna dei Monti outside Mario’s: Jennifer Montagu, specialist in Italian Baroque sculpture who curated the photo collection at the renowned Warburg Institute in London and later found the documents of Velazquez’s stay in Rome in 1650; Sir Denis Mahon, an art collector and respected scholar who later endowed the National Gallery in London with important Italian paintings; Erich Schleier, who became the curator of Italian paintings at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie; Philip Pouncey, the connoisseur of Italian drawings who carried the style Could include this link.

of thousands of artists in his head; Herwarth and Steffi Roettgen from Stuttgart (Steffi’s big illustrated book of Renaissance Italian frescoes is still in print). A cherished friend and sometimes roommate was the budding concert artist Marjes Benoist, in Rome to study with Maestro Guido Agosti; Marjes became the leading teacher of gifted pre-teen piano students at the Amsterdam Conservatory.

Carlo and Donatella

In the ensuing years the young couple, Carlo and Donatella, had an extraordinary international career. They worked on restoring what little was left of the greatest art loss of World War II in Italy: the chapel decorated by Mantegna in the Eremitani church in Padua, piecing together the remaining fragments from the bombing that leveled the church and fitting them into a reconstruction from old photographs. They were in charge of cleaning the frescoes in a famous chapel by the early Renaissance master Fra Angelico in the Vatican Palace. In Spello, a town not far from Assisi, they brought back to life another early Renaissance gem, an entire chapel decorated by Pinturicchio. In 2015 they were called to Padua to consult on saving the priceless frescoes by Giotto in the Arena Chapel from a rising water table.

They went to Afghanistan to help re-assemble the sculptures in the national museum that were bombed by the Taliban. They showed up in Bosnia during the Balkan war and organized the community to help them restore local treasures in the museum, recruiting a dozen young helpers to learn art restoration as they assisted in the recovery. They even traveled to New Mexico to restore the unique 18th-century paintings in a colonial church. To replace one lost panel, Carlo had a little fun signing an original work as “Carlo da Ancona.”

Buffalmacco Returns

But to get back to Buffalmacco: finally, in 2017, the restored fresco of The Triumph of Death was reinstalled amid considerable fanfare in Pisa. The Italian government issued a video commemorating the process, and to my great delight, right in the middle of it was my old friend Carlo Giantomassi, who directed the work. He does not look that different from a photo I took of him at Mario’s trattoria in 1971—same sandy beard, prominent nose, thoughtful intensity. A few more wrinkles of course. Sadly, Donatella did not live to see the end of all her work in Pisa. But seeing Carlo in the video made me say: “Thank you, Buffalmacco.”

Back to the Table of Contents

Seeing Poetry

By Randy Barker

Marie Claire knew that I listened to cassette tapes of poets reading their poetry, mostly in my car. She shared my love of hearing William Carlos Williams in his twangy voice reading “pinched out ifs of color” near the beginning of his Botticellian Trees. It was my joy in listening to poets that awakened her advice to me to write my own poems.

I have just said “awakened.” I believe in being awakened so much that I add an italicized phrase after every poem stating “Awakened by…” to denote how the poem came to be. Awakened means that I feel an urge to find words to celebrate what I see. Almost every poem I write starts with seeing. There is always a photograph. I see, I take the photograph, then I find words to write my poem, often the same day.

The photograph always appears with the poem when I print it and put it in an album. I refer to my collection of poems as “Poems I Have Seen.” I have been writing poems for 20 years.

I think of Emily Dickinson’s advice when I am finding my own words to celebrate what I see: “Tell all the truth/But tell it slant.” I first encountered Dickinson’s words about 30 years ago. By “tell it slant,” Dickinson seems to ask poets to avoid what some could not bear to hear told straight; but I think she also invites verse that opens up more than there is in “straight” telling of a story. I have had Emily’s points in mind when I write my own poems and when I read others’ poems.

My good friend Jim sends me his poems, and I send him mine. We like to talk about how we make them. We both say that our poems can’t help coming to us, and we both say the same of the words that make up the poems. Our poems are not fully thought out before pen hits paper (or fingers hit keys). They start with an idea, sometimes a title. Then there is the first line. Then the discovering, as if each word knows what words must come next and invites the followers in. We decide that the words are doing what we want them to do and often making changes so they do so better. They are celebrating the story we want our poem to tell.

I say to Jim I can find his stories even though his poems are sort of “cubist,” the way pieces and parts show up, usually connected to his titles, such as Sometimes Friends Aren’t Enough. The stories in my poems are always being shepherded along by the photographs that have awakened them. We both like to use alliteration, allusion, repetition of words and phrases, and other devices to win readers’ affection and attention. Occasionally there is an invented word. Often a metaphor or a symbol that holds up throughout the poem. Humor and irony are common. Moods run from joy to despair, mine more the former and his more the latter. I use line breaks for emphasis or to keep the reader on track, Jim less so. I also like enjambment, which is writing a thought from line to line without punctuation where it might be expected. We have both written poems in formal structures for the fun of it. I write lots of haikus and each of us writes villanelles with telling lines that come round and round.

I think of most of my poetry as memoir poetry. I wonder which of my poems on personal subjects tell stories in ways that remind readers of their own stories, something I like in poems I read. A few do this deliberately, such as Traveling to Brothers in Life, in which I recount remembrances of deceased friends who felt like brothers. The poem starts:

Here’s what I mean by traveling to brothers in life.

First I go at least twenty-five years

Thirty forty forty-five fifty-four fifty-seven.

One day, the sun gets in my eye,

Rising or setting,

And I stop. I have reached a brother in life.

Over 300 of my poems were awakened by what I have seen in France. They are collected as Poems I Have Seen in France, with the preface “Much of what I see in France awakens in me the pleasure of finding words to celebrate it.” In the first poem I wrote, in 1998, entitled Door Sounds of Ste Colombe, I imagine the sound of each door as I open it, at the old farmhouse where Marie Claire and I spend our summers. This poem reflects something I notice about rural France: all five senses are busy every day. It is a poem about touching and hearing. In others, I celebrate the other senses and another aspect of France that I notice almost daily: traditions. The Music in the Mass grew out of noticing that church music mixes joy and humility. Our Valleys and Plains reflects on the differences between the two river valleys nearby, one traversing sloping green hills, the other steep more rocky hills. And Your Holiness the Baguette compares a baguette to a bishop’s mitre, conferring upon it a sacred sense as it touches the vault formed by my hard palate.

The first verse of a villanelle introduces what I think of as a signature poem I wrote to celebrate Marie Claire’s father, who purchased our farmhouse in Normandy in 1929. I adored him. The poem describes an imaginary tour around garden with him. A six-foot stone wall surrounds it, and there are a number of fruit trees and several old buildings with red slate roofs. Legend has it that it was the home and clinic of a veterinarian long ago.

Le Jardin de Mon Pere

Le jardin de mon pere depuis dix-neuf vingt-neuf

Vous valez bien un tour avec les yeux ouverts.

Jadis les gens venaient ici guerir un boeuf.

My Father’s Garden

My father’s garden since nineteen twenty-nine

You merit a tour with our eyes wide open.

In the past, people came here to heal their cow.

***

I am a generalist physician, who like William Carlos Williams spent my life caring for patients. I never thought of myself as a poet until the joy of pondering what I see enticed me all the time and I discovered the pleasure of finding words to celebrate that.

Back to the Table of Contents

1/6/21

By Charles E. Sternheim

This flock, European descendants

released in downtown Washington D.C.

open-throated white-privileged

followers of Donald the King

mimicking Rudy’s rant

Junior’s declaration of war

keeping their anger in motion

climbing up the walls of the sacred

before a cloud of gas and dust

finally clogged their throats

as prison cells wait patiently

to lock them up behind bars.

Back to the Table of Contents

Random Acts of Kindness

By Barbara Orbock

Random acts of kindness have slowly shaped my philosophy of life. Every time I find myself slipping into the clutches of cynicism, some little act or other reaches my soul and rescues me. It reminds me that, in our vulnerability, how often mistaken we mortals can be. When this shaping began I can’t really say, but I do remember the first time I was truly aware of an awakening.

In 1959 car safety seats for kids were a joke – barely a seat and certainly not safe. I used them, but truly thought nothing about how well they functioned.

When my twins were 18 months old, I was doing errands and had them in these mediocre devices in the backseat of our Plymouth. Our last stop was at the neighborhood High’s for milk. I pulled into a space facing the front of the store. No other cars were around. I entered the store and quickly to the refrigerator and grabbed a gallon. I paid quickly and left High’s, only to see the Plymouth drifting slowly backwards down the parking lot incline and heading for the traffic of Taylor Avenue.

I screamed, dropped the milk, and ran. The car was only 10 feet from me and the parking lot was wide, but the Plymouth was gaining speed and I wasn’t going to make it. Then, from somewhere a man appeared, caught the door handle and swung himself inside. The car had stopped in mid-parking lot by the time I reached it. As I approached a young man of Asian descent emerged from the driver’s seat.

My first thought was my babies and I opened the back door to check on them. “Hi Mommy” came a unified, giggled greeting. After the hugs I turned back to thank their savior, but he had disappeared. To this day, I know not where.

The second major incident involved not only a random act of kindness, but also, trust. Dave had passed on his love of the stars and planets to our children. In the summer of 1968 there was to be a very intensive meteor shower. Dave was away on business so I piled the kids in the car and we headed for Cloverland Farms where we would have a view unimpeded by city lights. The trip was worth it and for an hour we were dazzled.

About 10 we headed home using the route around Loch Raven Reservoir. After rounding a bend I felt a bump and the car became more difficult to steer. I pulled over, got out to find just what I expected—a flat. I knew how to change a tire, but had really never had to.

“I can do it,” came a voice behind me. Jeffrey was 10 years old and had been following his father’s mechanical instructions since he was in kindergarten. He was as confident as his Dad that he could fix anything. I let him try because there was not another human anywhere, just some animals scurrying around in the woods.

Jeff lugged out the jack and put it in place. Together we tried to remove the spare from the trunk. As we were struggling, lights came around the bend and a car stopped. Three long-haired hippies got out and came toward us. Friend or foe, I knew not. All my worst fears raced through my brain.

“Need a hand with that tire, Sport?” one said and we were surrounded. I could smell the weed.

Jeff said, “Okay” and together they had the tire changed in a jiffy and the motley crew headed back to their car. We weren’t robbed, raped or thrown in the water. I thanked them profusely but they refused my offer of cash reward.

“Ya gotta real good kid there,” one said to me, as he lit up and then they drove away.

Next day I wrote a letter to The Morning Sun, thanking our unknown rescuers. It was printed and I hope they read it.

My most recent encounter with random kindness came two years ago in Washington. I had to walk from the National Gallery to Union Station to meet Dave. The quickest route takes you through a park area with a lot of trees. I went up Louisiana Avenue until I came to the park. A young African-American man was standing under a street lamp. It was getting dark. “Does this path go through to the train station?” I asked.

“Yes, ma’am, but be careful. It’s gettin’ dark and there’s no lights.”

I thanked him and walked quickly down the path. Not very far along I heard a noise behind me, so I walked faster. After what seemed like an hour, but was really seven minutes, I saw the lights and heard the car traffic around the front of the station. I sighed in relief. Then a voice called out.

“You’ll be okay now. Jus’ be careful crossing da street.” It was the guardian angel from under the street lamp. He had followed me.

In the early nineties, I was in a parking lot off Conway Street. An African-American man approached me and asked if I knew where a Mac machine was. I didn’t have an ATM card of my own at the time so I wasn’t really familiar.

“I’ve been walking around looking for one. I’m from Delaware and we have lots of machines there. I’m in a gas station on Russell Street, but I’m out of cash. My wife and two kids are waiting for me there. Do you possibly have five dollars to spare? I need enough gas to get back to Wilmington.”

I got out my wallet, not knowing if that was the last I’d see of it. When I handed him the money, he thanked me sincerely and was off.

Then I wondered if it was a line and if I’d been had. When I got in my car I decided to drive to Russell Street and check the two gas stations. And there he was, pumping gas while his wife held a toddler and another clung to her jacket.

I was very glad I had given him the money, but ashamed for being such a “doubting Thomas.”

Random acts of kindness continue to remind me of my humanity. They are not only a blessing to the receiver but also to the giver. As for guardian angels—do they exist? I prefer to think they do.

Back to the Table of Contents

Baseball Enters 2020

By Phil Hochberg

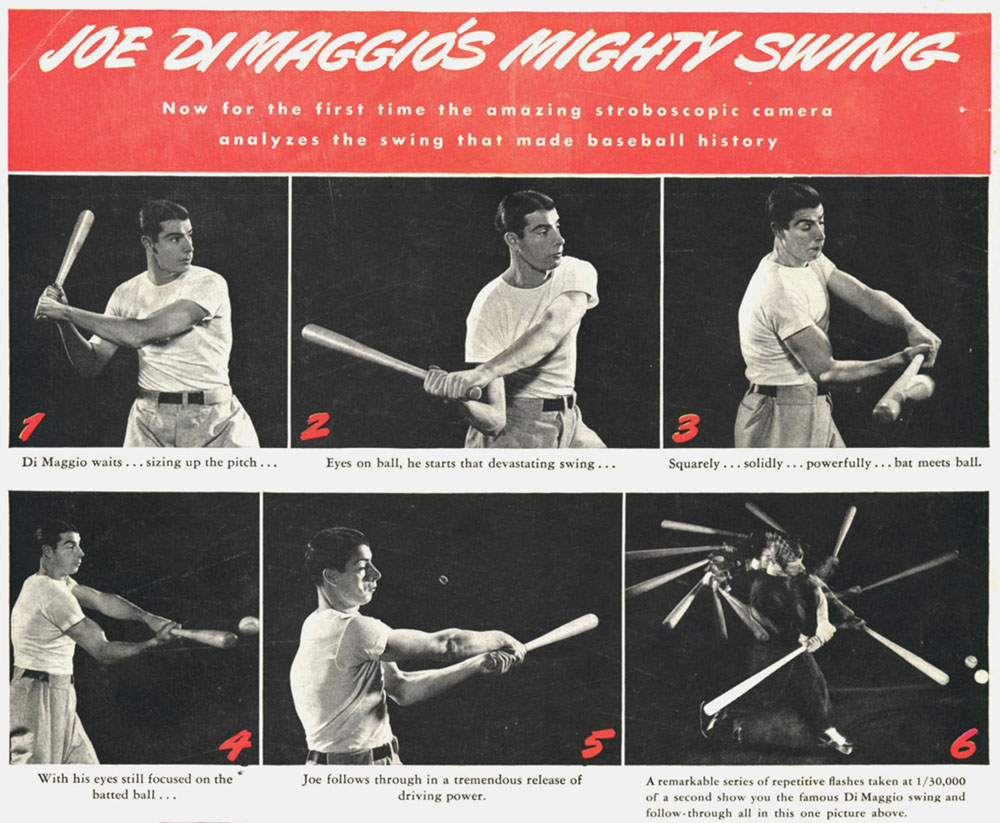

Every baseball fan – well, almost every baseball fan – knows that Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio had one of the picture-perfect right-hand swings. And every baseball fan – well, again, almost every baseball fan – knows that left-handed catchers are exceedingly rare. (The last left-hander with his primary position as catcher was some 120 years ago.) Apparently, the editors 20 years ago at Harper Perennial Modern Classics never got the word.

What’s the connection with Baseball Enters 2020? Bear with me.

In the course of his 56-game hitting streak in 1941 – actually in the June 29 doubleheader in Washington’s Griffith Stadium—DiMaggio was captured by an unknown New York Times photographer as he sought to break George Sisler’s then-modern-day 41 consecutive game hitting record.

DiMaggio, of course, went on to hit in 56 consecutive games, a record that still stands and has never been seriously challenged.

In 1974, Sports Illustrated developed a “Living Legends” art series of great sports figures. Well-known artist Harvey Dinnerstein created a 24×32 oil painting of the iconic photo and named it “Wide Swing,” perhaps the most well-known baseball painting ever. It was produced in autographed prints, as well, and used as the cover for Diamonds Are Forever: Artists and Writers on Baseball, published in conjunction with the Smithsonian.

In looking at it, you can almost feel DiMaggio driving the ball into deep center field. Dinnerstein later was quoted as saying that the original painting depicted DiMaggio wearing long sleeves. Before the painting was published, however, Dinnerstein got a call from DiMaggio saying that he never wore long sleeves because his fans wanted to see his “rippling muscles.” Dinnerstein said that he then asked a muscular model to pose as he repainted DiMaggio’s arms.

From there, it only got stranger. In May 1989, William Morrow published Summer of ‘49, by David Halberstam, one of the great writers of the late 20th century. While Halberstam had written the definitive book of the Vietnam War – The Best and the Brightest – and other well-received books, he took time out to write six books about sports. A New York Times book review praised Summer of ‘49 and said:

Reconstructing the race of ‘49, Mr. Halberstam has gone behind the scenes and talked to every living veteran of the season except Joe DiMaggio, who the author says avoided his every approach. We learn of the tensions and passions that drove the two teams [the Yankees and the Red Sox], and the strengths and peculiarities of a remarkable cast of characters.

Wikipedia said: “…Halberstam depicted the 1949 Yankees and Boston Red Sox as symbols of a nobler era, when blue-collar athletes strove to succeed and enter the middle class, rather than making millions…” A reviewer for New England Sports Network called it one of the five greatest baseball books ever.

The hardback edition used a dust jacket painting of a player sliding home, entitled – of all things – “Sliding Home.” And the painting for that 1989 book was done by … Harvey Dinnerstein. (I have recently acquired that painting.)

Although it took 13 years for the paperback edition to come out, the publishers felt they had to use a different cover. They decided they would use another painting by Dinnerstein for the cover. Given that DiMaggio was a key player in that 1949 season, a painting featuring him – Wide Swing – would be ideal.

But somehow, somehow…the classic painting got reversed and showed up on a promotional card with DiMaggio batting left-handed, with the Yankee logo reversed and in front of a left-handed catcher. How, who knows? A Google search found numerous references to and pictures of Wide Swing, but not a single reference or picture of the reversed image. Someone (whose name is probably best forgotten) subsequently picked up the promotional card of the reversed Wide Swing and commissioned an impressionist painting of the reversed image for the paperback. There indeed was DiMaggio, batting left-handed and swinging in front of the left-handed catcher.

I had been familiar with the Dinnerstein original. (At one point I had seen it in a gallery in Potomac, MD, and had naively asked its cost. When told it was $100,000, I realized it was a little out of my price range.) To say the least, I was shocked enough to write to Halberstam. And the author – known not to suffer fools gladly – wrote back to me, on the reversed cover: “For Phil Hochberg, who caught my publisher trying to turn the great DiMaggio into a switch hitter. Best. David Halberstam.”

Suspecting Halberstam was likely a little less pleasant in his next note to Harper Perennial Modern Classics, the cover was immediately changed.

(Actually, the cover art was probably better in the wrong version. You would want the buyer’s eye to flow from left to right to open the book. In the correct version, the eye moves from right to left to the binding.)

And now, the bastardized painting is off the current cover of the paperback version. Pick up, if you can, the current version of the paperback and you’ll see a picture of DiMaggio and Ted Williams and just below it, heaven forefend, a photo of the original New York Times’ The Swing. Justice is done.

Phil Hochberg is an Osher lecturer. He was the Stadium Announcer for the Washington Senators from 1962 to 1968 and was Rex Barney’s backup Stadium Announcer at Memorial Stadium for the Orioles in 1981, 1982, and 1983.

Back to the Table of Contents

Harry, Adlai, and—uh—Me!

By Les Weinstein

The 2020 presidential election year has brought to my mind two other election years: 1948 and 1952.

In 1948 when President Harry S. Truman was whistle-stop campaigning (short visits by train) for a full second term, he came to Providence, Rhode Island to speak at a downtown rally. My friend George and I got excused from school to see him. What I remember most was that on the stage with him were Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, who were big supporters of his. Many years later I went to Independence, Missouri and took a tour of Truman’s house, as well as his Presidential Library & Museum, where there was an exhibit about this whistle-stop campaign. For each stop you could press a button and listen to his speech at that city. Unfortunately, the one for Providence was unavailable. I was very disappointed!

Four years later in the 1952 election I was a big fan of Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic nominee for president, but my father, a life-long Democrat, liked Ike (Dwight Eisenhower), the Republican nominee. At one point in the campaign, Stevenson came to Providence on a whistle-stop tour. George and I got excused from school to see him just as we had done for Truman.

I do not recall if Stevenson gave a speech in town, but he did make an appearance on the rear platform of the train he was on. George and I were standing very close to where he came out, when I heard some man in the crowd say: “Let this little boy shake your hand”. As I was wondering who the lucky boy was, the man boosted me up onto the train where Stevenson was standing. After we shook hands, I asked him for his autograph, but he refused; however, after the crowd booed, he relented and asked if I had a piece of paper. The only thing I had was a matchbook with his picture on it that I had gotten at Democratic headquarters before going to the train station. He signed the matchbook, but only his initials, AES, not his full name! This experience is an example of why he was not considered a good campaigner, not “a man of the people,” and too much of an aloof intellectual “egghead,” as he was called.

The next day, my parents got several phone calls from relatives in Boston to tell them that there was a picture of me with Stevenson on the front page of The Boston Record with a heading that said “An Obliging Candidate.” If only the newspaper had known the back story, the heading might have been “A Barely Obliging Candidate!” After that, I renewed my efforts to get my father not to vote for Eisenhower. I told him repeatably that if Adlai (we need him “badly”) got elected, he could brag that I had had my photo in the newspaper with the President of the United States. But to no avail! Despite my recent claim to “fame,” he voted for Ike anyway. I still have the photo, but I do not know where that matchbook is!

Back to the Table of Contents

K-K-K-K-K-K-Kathmandu

By Jim Herrell

For reasons never explained but never questioned, I’d been bumped to first class on the flight from Bangkok, so when our plane landed in Kathmandu I was more than a little buzzed from free champagne and the women attendants who served it. I was in Nepal because, although a confirmed couch potato for whom fetching the Post each morning from the end of my driveway was a hike, I’d nevertheless accepted an invitation from my high school buddy Skip and his wife Julie to accompany them and two others on a month-long trek in the Himalayas. Before arriving on November 7, 1999, all I knew about Kathmandu was the Bob Seger song, so I had much to learn.

As our plane landed, I saw cows running in the grass alongside the runway. In the terminal, pre-9/11 immigration/customs procedures were as pregnable as the “please wait for hostess to seat you” signs at Denny’s. The city itself initially seemed to be a place of blooming, buzzing, confusion – crowded, noisy, and predominantly poor. Streets were packed with cars, buses, trucks, pedicabs, motorbikes, bicycles, cows, donkeys, pigs, chickens, dogs, monkeys, water buffalo, trash, and people. In some parts of the city, adult men and children of both genders urinated in the streets, and small children defecated. In Thamel, the tourist area, hashish was sold, and often smoked, openly. Incense burned everywhere to mix thickly with the odors of animal dung, hash, car exhausts, and trash heaps. Traffic seemed chaotic, perhaps exaggeratedly so to Americans because driving is on the left. Many streets were narrow by US standards, and sidewalks were rare, so that buildings often fronted right on the edge of the road. When two cars passed going in opposite directions, there’d be a distance of only an inch or two between the cars on one side, and people, buildings, animals, and parked vehicles on the other. Pedestrian right-of-way was, apparently, an unfamiliar concept to Nepali drivers, and the horn seemed to be more important to a car than, say, the brakes.

Our hotel, the Potala Guest House, was surprisingly upscale, especially considering the rate was about $7 per night. Beds were comfortable, there was plenty of toilet paper (made in China, orange, and more like crepe paper than tissue, but functional), and shower water was abundant and hot.

It was holiday time; a festive atmosphere filled the city. Different Nepalis gave different versions of which holiday, but consensus favored “Diwali” (variously spelled), or “Festival of Lights.” Whatever the occasion, all night long people sang, played wooden flutes, and set off firecrackers.

Nepalis often greeted us and one another by saying “namaste,” with both hands together in front of the face and a slight bow. “Namaste” seemed to mean much more than “wassup?” We heard various translations, but Julie provided my favorite, from a book by Peter Matthiessen: “I honor the place in you that is light-filled and universal, where if you are in that place in you and I am in that place in me, there is only one of us.”

The first evening, the owner of the trek company we’d hired took us and our guides to dinner at his favorite restaurant. We had excellent dahl baht – rice with a curried lentil sauce, with which we’d become very familiar, and some savory barbequed chicken. There was also a plate of cooked spinach-like veggies – saag – a dish that only one of our trekking party enjoyed. For dessert, we were served a yogurt something, which I didn’t like, and a glass of warm saké, which none of us liked.

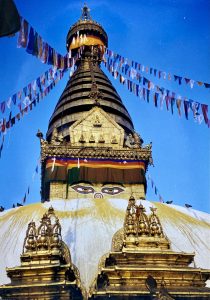

The next day in Kathmandu, we visited the “Monkey Temple” (Swoyambhunath Stupa), a beautiful Buddhist shrine also used by Hindus, situated on a hill with wonderful views. There’s much ecumenism in Nepal; many shrines are multipurpose, and many Nepalis to whom we spoke said they are both Hindu and Buddhist. There were more tourists than worshipers at the stupa, and more monkeys than tourists. We noted similarities to large Western churches and religious rituals – gargoyles on the rain spouts, people lighting candles for the dead, prayer accompanied by touching of head and heart. On the side of the temple with the best view, several men engaged in vigorous martial arts routines, and musicians played.

After the Monkey Temple, we had breakfast at the Northfield Café, featuring the Jesse James bar, owned by a Peace Corps veteran from Northfield, MN, site of a notorious James Gang raid. The café specialized in Southwestern cuisine, so in Kathmandu I had an omelet stuffed with pico de gallo, heavy on the jalapeños. After lunch, we visited the Tibetan Refugee Center, where some of our group spent lots of money buying rugs. I bought only a wooden Nepali flute, which I couldn’t make toot.

For dinner, we went to a restaurant in a building that once was a home for Buddhist priests. Inside were several large rooms with long banquet tables at which diners removed shoes and sat on legless cushioned chairs. A prix fixe multi-course meal, sequentially served, included a nut mixture, delicious garlic-tinged potatoes, steamed meat dumplings, dahl baht, saag, and several items to eat with rice – a black bean sauce, various fried veggies, mutton, tasty fried chicken. For dessert there was another yogurt thing. As on the previous evening, we all received warm saké, ceremonially poured from three feet above the table into a small cup. Tonight’s waiter spilled a lot of it; the waiter last night had splashed not a drop.

A couple shared our table, he an American, she a Brit. When the woman told us she was from Yorkshire, “a large county, the Texas of England,” Texas expats Skip and I noted that the lakes around Austin could swallow the whole of England – O.K., maybe not literally true, but hey, don’t mess with Texas. The couple were “on holiday,” although from what was never clear—perhaps from their Maine-to-Georgia hike of the Appalachian Trail. As were we, they were in Nepal to hike the 150-mile Annapurna Circuit. They arrived in Kathmandu half-way through a 12-month, round-the-world trip – their third such. They had trod on seven continents, ridden both the Orient Express and the Trans-Siberian Express, hiked, swum, skied, sailed, ridden dog sleds, scuba-dived, windsurfed, snowshoed, been to every there, done every that. They spoke of their recent crossing of the Gobi Desert as casually as I might speak of going to Safeway to pick up some bread. They were intelligent, witty, charming, life-loving people who led exciting lives. “What do you do for fun when you’re not hiking the Himalayas?” the man asked me. “Crossword puzzles,” I mumbled into my dahl baht.

Dancers, singers, and musicians performed while we ate. Instruments included several drums and cymbals, a wooden flute, and some variant of an accordion. A musical troupe at the Monkey Temple had played the same type of instrument, operated with the keyboard on the floor rather than held. Dances featured stylized pantomime, hand gestures, and facial expression, with little contact between the sexes. Each of the two women dancers had a silver pin in her left nostril, and a loop in the fleshy fold between her eyebrows. The two men were more fluid in their movements than the women, and their expressions more animated. After their performance, the dancers and musicians donned jeans and T-shirts, piled into an old van like college kids, which perhaps they were, and sputtered and backfired into the Kathmandu night.

The next morning, we left Kathmandu to begin our trek. Once my culture shock had abated, I had come to appreciate the city as a vibrant, multicultural, international place, rich in its textures, warm, welcoming. Nepalis were friendly, tourists received Hawaiian-style leis at the airport, prices were low, we loved Nepali food (not counting saag), amity within the traveling party was high, we had time to depressurize from real life and the long trip across the Pacific, and we were eager to begin our adventure.

Epilogue. As we neared the metaphorical and literal high point of our trek, Thorung La pass, altitude about 3.3 miles, we passed the restaurant couple going the other way. The man had developed early signs of altitude sickness and had to turn back. Although I wished him well, I confess that I may also have experienced just a teeny bit of schadenfreude.

(My thanks to Doris Forster, whose article, “Namaste,” in the Spring/Summer 2020 Osher at JHU Journal issue, stimulated me to write this narrative.)

Back to the Table of Contents

My Left Hand

By Neil F. Gordon

The year 1956 was considered a good time to be a 15-year-old teenager in Baltimore, Maryland. Rock and Roll was dominating the music scene, we were three years past the Korean War, President Eisenhower’s interstate highway plan was already paying dividends in reducing travel times by car, and I was just getting my learner’s permit to start testing my skills behind the wheel of Dad’s Buick Roadmaster.

It was a typical fall day in November. As a sophomore at the Castle on the Hill, better known as Baltimore City College High, I got off the bus after a 45-minute commute from 33rd Street and the Alameda to my stop at Clarks Lane at Park Heights Avenue. Sore and tired from a JV football practice, I hurried down the two-block walk to our apartment house unit. Just months before, glass storm doors were installed on the front doors of the complex. As I ran up the stairs, I stumbled and began to fall forward. My reflex reaction was to reach out to break the fall. Instead of breaking my fall, my open left hand broke the glass of the front door and I then fell to the ground.

I remember a scrape on my left knee but was not aware of any pain to my hand. As I began to get up, I saw a pool of blood where my hand had been, which was coming from an open wound that ran from my middle finger to the pinky. At that point, I ran to my door and yelled for my mother to open it. Fortunately, she was home and opened the door. I ran past her to the kitchen sink and ran cold water over the wound. I grabbed a linen towel and pressed it against the wound. My Mother’s initial reaction was to call her sister-in-law who was a pharmacist and served as her medical expert.

My aunt had me get an ice pack on the wound ASAP, and have my Mother drive me to Sinai Hospital, which was about two miles away. She would call a doctor to meet us at the ER. About an hour later, after the wound had been cleaned and the bleeding controlled, Dr. Mark Gann introduced himself. He was the head of surgery at the hospital, which meant my aunt did have some influence. He sat us down and was straightforward with us. He said that all he could do for this was either sew the wound up or amputate the three fingers. Every nerve and tendon had been completely severed. But, he said, there is one local surgeon who is a pioneer in saving and rehabilitating these types of wounds. If he was available, he could possibly give me a better prognosis. Dr. Gann called his office and he was in at the time.

Two hours later, we were at Union Memorial Hospital talking with Dr. Raymond Curtis. He was small in stature, spoke softly, and had a very commanding presence. He said because the wound was clean and precise for easier access, he felt good about the chances of saving my fingers. At around 11:00 p.m., I was wheeled into the OR and a six-hour surgery commenced. When I woke up, Dr. Curtis was talking with several other MDs describing what he had done, and to me it could have been a foreign language, since I was not familiar with any of the names of the nerves and instruments he was referring to. I had a cast on my left lower arm and the three fingers were attached to heavy rubber bands that were anchored to what appeared to be a hanger-type attachment. The swelling was very noticeable, and for the next few days I was moved around the hospital in a wheelchair and examined by many doctors. I felt like a celebrity.

What I never realized at the time was just how new and revolutionary this type of orthopedic surgery was. I left for home after three days and went back to school the next week. In another few weeks, I had the stitches removed. I had pain sensations in my fingers which was a good sign. Next on my list of things to do involved a regimen I remember as close to torture. I was assigned a physical therapist at Union Memorial three days a week for the next six months. The good thing is it was only a 10-minute walk from my school and on the same bus route. The therapist was Stan, a burly 200-pound man of about 35. I would come into his room and dip my hand in hot paraffin wax which formed a glove around the hand and made the manipulation more effective. He used cocoa butter and would rub it into the fingers. Then the fun started as he would pull my fingers back to break the scar tissue. It would be a game of how long I could hold out before crying uncle. Without this pain, Dr. Curtis told me, his work on the hand would be noticeable, and I would not benefit with maximum results that he claimed could be 90% return to normal use and feeling. Over the next two years, I would see him at his office every three months.

There were a few seminars he asked me to attend at auditoriums for presentations of his work, and when he called me up to the dais, I saw multiple color shots of the pre-surgery wound, the surgery itself, and the post-surgery. He’d then have me demonstrate the dexterity and strength of the fingers. Afterwards, a procession of hand surgeons would talk to me about things I could do and not do. The only limitation was the ring finger had a slight bend at the joint of the fingertip and about 80% of the feeling.

The next year of high school, I was held out of contact sports, but resumed sports activities in college. Let’s move the clock up 60 years and speak of the cathartic experience which led to this story. A very close friend of ours died unexpectedly two years ago and her daughter happens to be a doctor on the staff of Union Memorial Hospital. For some reason, I googled Union Memorial and saw the Curtis National Hand Center prominently featured. It opened a stream of memories of my past that I hadn’t thought about in years. Dr. Raymond Curtis, by the grace of God, happened to be in the right place at the right time and saved my left hand. I began to think of how fortunate I was. I’ve always tried to be generous in my charitable giving and volunteer work with non-profits, but I asked myself “have I really repaid the debt of my good fortune in terms of personal growth?” My answer is that I can do much better in the remaining time that I have on this earth.

The past few years, I’ve seen the country I love being torn apart by political and racial division. Social media has replaced human personal contact, and COVID-19 has only exacerbated the situation. This is a time when those that have been fortunate to prosper need to do their part in helping to bring those in need the opportunity to take the right path to personal achievement. I would like to honor the memory and work of Dr. Raymond Curtis who gave me that opportunity.

I have been in touch with the philanthropy department for MedStar Health, which is the parent company of Union Memorial Hospital, and have made a gift to the Curtis National Hand Center. A donation can never repay what was given to me all those years ago, but it is a start.

Back to the Table of Contents