Travel with Osher!

Fall/Winter 2024

Volume 34, No. 2

Contents

The Veteran

By Jeanne Marie Randall Wills

The World War II foxhole held pieces of three dead men. The lone survivor was stunned, blood-spattered, and crumpled on the ground; he had collapsed mid-sentence in conversation with his classmates, his friends. He went to them, checked for any sign of life, then laid the pieces of his friends together inside the foxhole. Through the unending night as the incoming mortars fell, my father sat on the front line and watched over his friends hoping a torso would stir even as he knew they would not.

Twenty-eight newly arrived combat engineers died that night in the autumn of 1944 when they were ordered to the frontline while the Division waited in France to join forces with General Patton’s Third Army. My father was under the command of General Twaddle, in the 95th Infantry Division, but General Patton dove in, angrily demanded changes in command in Twaddle’s Division and swore blisteringly to the troops and their leadership that if they lost their engineers, they were dead in the water and could not move forward. Combat engineers moved ahead of the troops, ahead of the front line to prepare the terrain, build bridges, mine strategic sites, navigate rivers, and support mechanized troop movement. Engineers were to be in the rear of the Army until they were needed for operations ahead of the troops. Soon thereafter, the order came for the battalion with my father, Robert Randall, to join the Third Army’s mad dash slashing through France “covering distances unthinkable in previous major conflicts.”

Casualties mounted under fire during the assault’s river crossing near Mainz. The boats were so heavily laden that the tops of the shallow boats were only inches above the surface of the water. Engineers steered and paddled the boats they had loaded with troops. At the front of each boat a soldier swung a smoking pot to cloud the air and hide the men from enemy snipers. The pot smelter in a neighboring boat was hit in the chest and fell into the river. With focused clarity of thought, Robert brought his boatload of soldiers to the bank. The men ran forward, and Robert saw one take a bullet and fall to the ground. He asked another engineer to leave the boat and together under fire they ran to the wounded man and carried him back into the boat. Robert laid out plans to also bring back the fallen man in the river, but before they pushed away from the shore, a new sergeant came running away from the battle and jumped into my father’s boat, which was returning to pick up more troops. He refused Robert’s course to pick up the fallen man in the river. He refused Robert’s course along the river where the medics waited. The wounded soldier was later transported ruggedly over land; he did not survive. The morale among the men left on the other side of the river listening to the engineers recount the conditions their friends had encountered, and the wish for wounded soldiers to be rescued, led to a request to give my father an award because of his efforts to bring back wounded soldiers under fire. The retreating new sergeant demanded an award for himself because he had been in the boat, too. The request was extinguished, which disappointed the men who did not want wounded soldiers to be abandoned.

A small unit of engineers on a mission ahead of the army encountered a stream of foreign soldiers coming straight toward them from enemy territory. There were no US troops accompanying the engineers; they were alone and undefended. “Hot Shot Sutton” had picked up a Gatling gun earlier from the battlefield, had repaired it, and carried the gun in the jeep with ammunition. Hot Shot ran and jumped onto the back of the jeep; he quickly set up the cranked machine gun and aimed it at the foreign soldiers who continued to come straight toward the undefended engineers. A second engineer jumped on the radio reporting the oncoming foreign troops, calling for backup from the US Army. My father aimed his rifle and some of the foreign soldiers stopped. They raised their hands and began to collect into a large, loose group maintaining a distance from the engineers who moments earlier had been busily working with nothing on the horizon. The paltry handful of combat engineers held their cool waiting for the US Army to arrive. The foreign soldiers were interrogated, and most were reported to be Russian troops who had been prisoners of war at a camp nearby. When the German soldiers fled, the prison guards abandoned the camp to avoid the advancing American Army. The starving Russian prisoners of war had freed themselves and had begun walking away from their fleeing German captors and toward the US Army.

When their officer training program was discontinued six weeks before the fledgling engineers completed their first year of college, my father and his classmates entered the army as Private First Class (PFC) enlisted men, urgently needed to replace the rapid attrition of combat engineers lost in battle. The prejudice and resentment that one category of soldier may hold against another, the practice of segregating officers to socialize separately from lower ranks, and attitudes against college men brought frustration and increased danger to this group of PFC combat engineers, who sometimes functioned independently and sometimes found themselves under the command of questionable leadership. The horrific casualties among my father’s classmates on that night, when orders issued by an incompetent man sent them to stand watch in front of the troops, left indelible trauma memory of sitting alone through the night with his lifeless, dismembered friends.

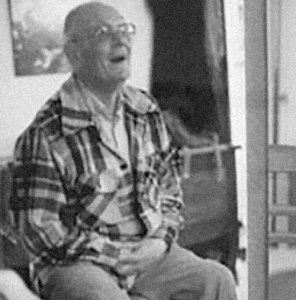

It was only near the end of his life that my father was able to tell us of his traumatic battle experiences in the World War II European Theater of Operations (ETO). Without interrupting, I listened to his halting narratives and allowed a free flow of trauma memory to surface with the accompanying emotions. Piece by piece his narrations came with minimal questions. I knew his ghosts came out at night and that he needed benzodiazepine to calm his thoughts and to be able to sleep. I knew from his sleep doctor that his brain was dependent on this medication and without it he would suffer seizures. In his eighth decade of life, my father’s medication was repeatedly and cruelly stolen; Robert suffered multiple grand mal seizures and was gravely injured. We struggled together as all families of combat veterans will do throughout their lifetime to pick up and heal the shattered pieces of their loved ones.

Honorable Discharge record:

Robert Edward Randall arrived ETO on 17 Aug 44 returned USA on 5 Jul 45. Honorable Discharge 30 November 1945. Battles and Campaigns: Northern France, Rhineland, Central Europe. Decorations and Citations: Overseas Service Bar, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 3 Bronze Service Stars, American Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Good Conduct Medal. Lapel button ASR Score 2 Sharpshooter-Rifle. Total Length of Service 1 year 7 months 29 days, Foreign Service 10 months 26 days.

Back to the Table of Contents

Lost But Found

By Margaret Dowding

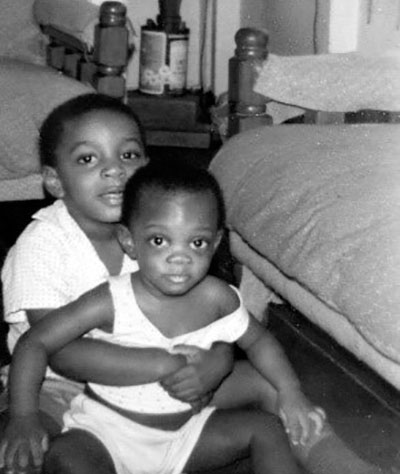

“Margaret, you do not have the boys! You are leaving them. Here they are.” Words spoken by my mother as I was going through Guyana Immigration in August 1985.

Summer 1985, and our entire family was about to migrate to Belize. For the previous four years Sam had been working at USAID/Guyana, and the office was closing after more than 30 years of US government assistance to our country.

Sam was offered a job in Belize and without hesitation we decided to pack up, inclusive of our two toddlers, and move. This would be our first time away from family and friends, after living in Guyana for all our lives till then. Would this be a wonderful experience for us, or one of regret? Will our boys aged four and one adapt? What about a job for me? I was an auditor in the Government of Guyana (GOG) Audit Department, what would I do? Become a stay-at-home mother? So many questions, emotions to work through, but first I must pack and travel to Belize via Miami.

Sam had left for Belize a month earlier on July sixth via Barbados, and I was left to pack our belongings with the assistance of skilled movers. The packing started, and they were in every room. Items that were not to be packed were being packed (little did I know this experience would be the first of many—nine times total). Thankfully, the boys were with their maternal grandparents and could not add to the panic and confusion.

The time was fast approaching for me to leave; however, I was not sure that this could be accomplished, as I was “supposedly” a contractual employee of the GOG. During my five years at the University of Guyana, inclusive of a mandatory year in the Guyana National Service, I was paid my monthly salary. The Government was allowing government employees to attend University on a full-time basis, but we had to sign a contract to serve at least five years after graduation. Further, to leave the country, travelers had to obtain clearances from the Public Service Ministry, as well as the local Internal Revenue Service. I knew that I had not signed a contract; however, I was still very apprehensive about what would happen when I got to the airport, as the names of government employees under contract were kept in a log at the airport.

The day arrived for me to leave the country, and I could not foresee that it would begin so disastrously. My brother had arranged for his driver to take me, the two boys, my mother, my in-laws, and all our luggage to the airport. The flight was leaving Timehri Airport at 7 a.m. and check-in was three hours before. Because it took one hour to get to the airport, the driver was to pick me up at my parents’ home at three, then pick up my in-laws by the floating bridge by 3:30, and then proceed to the airport.

The three o’clock hour arrived for me to be picked up, and there was no car or driver. My dad, who was a very punctual man, said, “Where is this guy? He is late.” We did not have a phone number for him, so we waited. At four, with still no car coming, and numerous attempts to reach my sister-in-law (SIL) on the phone, my dad decided that he would ride over to my SIL’s home and ask her to drive us to the airport. My father was not to be deterred. My dad placed me on the bar of the bike (that same bike on which my brothers failed to teach me to ride), and we went over to my brother’s home. Thankfully, it was not too far away. We got there and rang the bell many times and there was no answer. She was a sound sleeper. My dad then began to pelt small pebbles on her bedroom window while calling her by name. This eventually worked. We got her up and she agreed to drive. By this time, it was now close to 5 a.m., and her car only accommodated five people. Would I be able to pick up my in-laws who were waiting at the Harbour Bridge, and who had no way of knowing what was happening? There was no time to think about the end result, as we had to return to my parents’ home to get the boys, my mother, and the numerous bags that made up my luggage—four suitcases, baby bag, pocketbook, children’s play desk with many small numbers and letters, and one hand piece. At 5:30, we were on our way.

The drive to the bridge was okay, as there were some road lights, but I panicked as I kept looking at the time. We were extremely late, and I was not sure that we would be able to get on the plane. We got to the bridge and picked up my in-laws. We are now packed very tightly in the car with a driving speed of 30 mph, peering into the dark as there are no streetlights on this section of the road. My SIL is incredibly nervous, as there are huge trucks trying to overtake, while another truck of the same size is coming at her from the opposite end with their high beams on, and horns blaring. What drama!

We arrived at the airport with little time to spare at 6:30 a.m. The boys and I are the last passengers to board as the flight is leaving on time. I handed in my bags at the ticket counter, and then proceeded to Immigration. My heart is beating very rapidly. “Ma’am, passport please. We must check to see if your name is on the do-not-fly list.” I wait, barely breathing, for 10 minutes, and the officer returns. “You are okay to travel.” I am relieved. I still must go through customs. I turn to wave goodbye to my mother, in-laws, and SIL, when my mum says, “Margaret, you do not have the boys! You are leaving them. Here they are.” It was at that moment that I realized that with all the various bags that I had in my hands, and on my shoulders, I had forgotten the boys. The two most important pieces that should have been in my arms were Vidal and Gareth, as they were our world and the entire reason for our move to Belize.

Back to the Table of Contents

Life Lesson #11

By Jim Herrell

In the spring of 1961, I bought my first car—a ‘54 Ford convertible, black ragtop, body the color of French Vanilla ice cream, red upholstery, one of the most beautiful cars ever. With money earned from a part-time warehouse job, I paid cash, and believed the car would justify every minute I’d spent working.

A college freshman then, I was considered something of a dweeb by most girls, so in addition to anticipating the simple joys of driving a convertible, I expected my new car to enhance my image. But when I arrived—top down, sunglasses on—to pick up the first girl to ride in it, she said, “For God’s sake, Jimmy! Put the top up! Can’t you see I just had my hair done?”

A dweeb in a hot car, I learned soon enough, is, nevertheless, a dweeb.

Back to the Table of Contents

Chains of Irony

By Suresh Arora

My body convulsed uncontrollably. Hands struggled to restrain me. “More hot blankets!” echoed in the chaos, followed by a rush of warmth. Days later, mild burns marked my skin.

Memories of that day are fragmented, left unparsed…

“Lost him,” or maybe, “We’re losing him,” echoed. Yet, within, I whispered, “I’m still here, I can hear you.” “Bleeder found!” A command, “Apply pressure.”

Moments later, a flashlight pierced my left eye, questioning, “Can you see?” I nodded. A sense lingered—I might have lost my eye—yet relief swept over.

Afternoon of January 19, 1984, Trauma Center, Georgetown University Hospital. Lunch and dropping my daughter at the bus stop, a routine disrupted by a snow-dusted day.

I recall Middlebrook Road, heading north. Memories blur after. An ambulance ride, debate on routes to the Trauma Center—ambulance over helicopter.

Piecing together with colleagues from the office who rushed to the scene—an inexperienced driver, fresh license in hand, crossed the median. Head-on collision, shattered glass, and a collapsed car.

My daughter waited at the bus stop. The bus didn’t come; the road was closed for hours.

Back at the Trauma Center, stability declared. Tests planned. The stretcher moved; my wife’s tears and grip. Reassurance passed through faint words. “Chain around his neck, need to cut it,” spoken. A golden gift from my mother, pleaded, “It is gold! There’s a clasp—don’t cut it,” met with soft laughter…

Irony lingered within—I worried for a chain while gifted another chance at life. Gratitude surged, and darkness enveloped.

Back to the Table of Contents

Becoming “Mon Fils”

By Randy Barker

My future wife did my proposing to her parents because I did not speak French. Immediately, they said, “Nous etions deja au courant” (we already knew). I felt warmly embraced. That day and ever after, I never sensed that Marie Claire’s parents regretted that, because of me, their oldest daughter would spend her life far away in the United States.

We announced our engagement in February 1967. By December 1993, when my father-in-law…my “beau-pere” (beautiful father)…died, I had been “mon fils” (my son) for 10-plus years. In February 2000, when my mother-in-law…my “belle-mere” (beautiful mother)…died, “mon fils” even longer. (Note: “fils” is pronounced “feese,” rhymes with geese.)

I believe that the notion of making me their third son (fils) came to mind when I became an orphan. My widowed mother, whom they had gotten to know, died in 1984. Since 1968, we and our three daughters had spent several weeks in France each summer, mostly with Grand-Pere and Grand-Mere. I think that the summer after I had lost my mother was when Pierre Palisse first called me “mon fils.” I recall feeling surprised and touched. I missed having a parent to listen as I told of my doings and thoughts, what I have always regarded as the most important role a parent plays, and now my beau-pere had called me “my son.” Soon, Denise Palisse, my belle-mere, joined him to call me “mon fils.”

To prepare a remembrance of becoming “mon fils,” I scribbled down a long list of vividly recalled moments, a list that brought Pierre and Denise Palisse alive. Two examples would be the following:

Pierre: His extrovert-par-excellence miming of a man at the movies whose facial expressions covered the whole gamut of emotional responses to what he was watching…and her total loss of composure as she burst forth with unbridled laughter, uncommon for her. She showed emotions sparingly.

Denise: Her gift of knitted woolen sweaters to one and all in the family. Many summers she had us pick wool colors from a catalogue, and during the winter she knitted our new sweaters. How I remember the beautiful burgundy sweater she knitted for me one year.

Pondering my list of memories, such as that one, I felt ready to explore how they and I entered into a parent-son relationship. Much of that process, I think, had to do with their special relationship to each other. Their world was, above all, about the family lives of each of their four offspring. They had no close friends, and they loved taking walks, working in their garden, reading books, and staying in touch with four young families. Their day-to-day was very different from the socializing life styles I knew in my world of family and friends in the US. As I think about it, their almost exclusive life spent with each other meant that they had the time and the readiness to welcome another son. I can easily call up exchanges such as Pierre saying, “Mon fils, tu serais gentile de m’aider avec…” (my son, would you be good enough to help me with…) or Denise, “Merci mon fils…j’avais besoin de l’ail pour mon gigot…et tu m’a chercher ce bout d’ail a Houlbec” (thank you thank you my son… I needed garlic for my leg of lamb, and you have gone to get garlic for me at Houlbec).

Because we were across the ocean, the way they and we kept up was through weekly letters, Pierre and Denise alternating weeks. In their long letters they recounted details from the families of each of their offspring. I like to imagine that, after writing the weekly letter, the author read it to the other. The letter was, after all, meant to be their shared voice. Here was the conjugal relationship I had come to appreciate, and they were co-writing those letters to both Marie Claire, a daughter, and to me, a son.

My son-hood brought me to places that a loving son goes, places where he lends his love when times are difficult for his parents. The locus for this son-hood was Pierre’s devastating recurring depression. In the late 1980s, this man, who lit up every day for those around him, lost all appetite for life, becoming inanimate, unreachable, irritable. During our visits while Pierre was depressed, we and our daughters tried everything we could to awaken Grand-Pere’s old self. One day, I knelt by him, his head drooping down, held his hand, and proposed that he and I take a walk around his garden. He agreed. After agreeing to walk with me each subsequent day, he began to acknowledge Grande-Mere’s delicious meals, and in the weeks ahead (what we learned after returning to the US), he emerged from that episode of depression. Perhaps I had been what my “father” needed at that moment. What affected my son-hood as powerfully as Pierre’s depression, was Grande-Mere’s unfailing love for him at that time, love I saw every day when we were there, and love that I thought about after we had returned to the states. I cannot say what, if anything, I did for Denise besides quietly loving her for how she was. I often told others about her, calling her “my hero,” as I described her way with Pierre. Her love for me as her third son was very present when I thought about her as my hero.

Becoming “mon fils” in the Palisse family felt like a natural process when it occurred. My reflecting on it 50 years later tells me that Pierre and Denise were uniquely ready, through their loving relationship and their life-style, to offer this precious gift to me. And I was ready to live that gift.

Back to the Table of Contents

A Few Good Years

By Barbara Pallas

She thought about how the years had been extremely good to her. She was only 15 at the time, and he was 21. It was July, 1965, and she vividly recalled her mother’s reaction as a tall, dark-haired, well-groomed male stepped out of the “looked like new” Chevy Malibu and crossed the street to the house for their first date. “That is not a boy, that is a man!” said the mother. “Oh, mom—he’s really nice!” the daughter replied. Over the years all three shared many laughs about that first meeting.

She thought about how the years had been extremely good to her. She was only 15 at the time, and he was 21. It was July, 1965, and she vividly recalled her mother’s reaction as a tall, dark-haired, well-groomed male stepped out of the “looked like new” Chevy Malibu and crossed the street to the house for their first date. “That is not a boy, that is a man!” said the mother. “Oh, mom—he’s really nice!” the daughter replied. Over the years all three shared many laughs about that first meeting.

He was a junior in college, and she was a sophomore in high school. He had a job and a car, which distinguished him from her usual dates and his idea of a night out was not a movie and a milkshake. He took her to her first professional football game, her first live theater performance, and her first “you need to get dressed up” date at a restaurant requiring reservations. He was the older, more mature man, the college student with aspirations to be an English teacher. She was a starry-eyed high-school sophomore just beginning to have thoughts about what she might want to do when she graduated from high school.

Their initial relationship lasted only a few months and although they both enjoyed their time together, as summer ended, his schooling and his decision to reunite with a former girlfriend caused them to separate. She reasoned that he probably never really cared for her anyway. If he didn’t want her, she certainly did not want him! “Too many fish in the sea!”—the mother’s words again.

Weeks turned into months and years, and she occasionally saw his friends who mentioned that he was graduating from college and was engaged. “I don’t care!” she said. “I wish it were me!” she thought. Most of her time was spent preparing for her high school graduation. She was dating someone who wasn’t special, but weekends could be lonely without someone to share them.

She was at her best friend’s house, planning a bridal shower for a fellow classmate when her mother called to tell her that “he” had called. In that single moment, when her stomach felt like a thousand butterflies had taken up residence, she said out loud what she had unconsciously always known—“I love him and I’m going to marry him.”

“You are crazy!” her friend said.

“Maybe!” she replied.

The next years were the happiest in her life. They dated again, became engaged, and married within 18 months. He was a high-school English teacher, she worked at an insurance company, they bought a small house and marriage was everything she dreamed it would be. She settled into the role of the wife who idolized her husband. He was a caring husband, a good provider, and the best friend that she had ever had.

She became pregnant after their first anniversary, and they were ecstatic with the arrival of their firstborn, a daughter. She was the apple of Daddy’s eye and for Mom, the fulfillment of some inner yearning. Together they marveled at this product of themselves. A few years later another daughter was born, and their family was complete.

They had a beautiful home, an easy and carefree lifestyle, and as they watched their children grow, their marriage thrived. She often thought that they were “used to each other,” as only two people who have loved and lived together for several years can understand. It was comforting to know that he was always there for her. When she needed a friend, he listened to her. When he wanted advice, he asked her. She thought that she was the luckiest woman on the earth. He was an excellent father and despite his workload as an English teacher, he always had time for his little girls, who learned their vowels before they could say their ABCs. She could hear him saying “A, E, I, O, U—and sometimes Y” and his daughters would repeat them and perform what they had learned in front of their grandparents to much laughter and hand clapping. She was the wife, mother, and homemaker who stayed at home with the children, managed the money and anxiously waited for him to arrive home each evening. When their children started school, she wanted to find a part-time job. It was difficult to work and keep house, but he encouraged her and shared the household duties with her. She felt fortunate to have him as her partner.

At a time when most of her friends were either separated or divorced, she was content in knowing that they shared none of the marital problems experienced by them. Her life was centered around him and their family. She spoiled him, she knew, but she loved him. “Why do you do so much for him?” her friends would ask. “He does as much for me,” she replied.

As she stood by the road on that clear, end-of-summer day when trees provided a preview of the season to follow, she thought about these things and smiled. As she gazed down at the marker that bore his name, she thought how the years had indeed been good to her.

* This was written by me in 1982, my first assignment in my first college-level Composition class. I am a member of Diane Scharper’s Memoir Writing group.

Back to the Table of Contents

Khrushchev, July 4th, Basketball, and Me

By Marvin Kalb

The word spread quickly through Harvard’s Russian Research Center in the fall of 1955. The American Embassy in Moscow was in urgent need of a Russian-speaking press attaché, someone who was unmarried, had “top secret” clearance, and could be there in two weeks. At the time, I met those needs. I was unmarried, spoke Russian, had the necessary clearance from previous work with Army intelligence, and the thought of a Moscow assignment felt more compelling than continuing my PhD program at Harvard.

The word spread quickly through Harvard’s Russian Research Center in the fall of 1955. The American Embassy in Moscow was in urgent need of a Russian-speaking press attaché, someone who was unmarried, had “top secret” clearance, and could be there in two weeks. At the time, I met those needs. I was unmarried, spoke Russian, had the necessary clearance from previous work with Army intelligence, and the thought of a Moscow assignment felt more compelling than continuing my PhD program at Harvard.

I applied, and a week later, a State Department official interviewed me and concluded, “This is a marriage made in heaven.” It was not heaven by my definition, but I did spend 13 fascinating months in the Soviet Union. I met many Russian officials, diplomats and journalists, traveled from one end of that vast country to another, and improved my command of the Russian language from good to very good. I had dozens of exciting encounters, but none more memorable than my first meeting with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. There would be many others over the years, but this one was special.

It took place at the July 4th party at Spasso House, the ambassador’s residence in Moscow. The night before, ambassador Charles Bohlen learned that Khrushchev had accepted his invitation to join him in celebration of the July 4th holiday, the first time a Soviet leader had ever agreed to participate in an American national holiday. It was Khrushchev’s way of turning a positive page in US-Soviet relations. Though Bohlen was delighted by the news, it left him with a problem. He spoke Russian fluently, but few others at the embassy did in those days. Suppose Khrushchev were to be accompanied by other senior officials, which was likely, who, Bohlen wondered, would talk to them in Russian?

Having few other options, the ambassador turned to me, his most junior attaché. If the minister of defense, the legendary Georgy Zhukov, were to join Khrushchev, Bohlen decided, he would be my responsibility. On reflection, that struck me as absurdly asymmetrical but challenging. Zhukov was a renowned 60-year-old World War II hero, who’d led troops in the bloody battle at Stalingrad. I was a 26-year-old attaché, a former PFC (private first class) in the US Army, whose military experience was limited to doing academic research in Washington.

Still, operating on the assumption Zhukov would accompany Khrushchev, I studied up on him and found, among other things, that Zhukov had a healthy appetite and enjoyed his vodka. Problem: at the time, I did not drink vodka or anything else. When it was time for a drink, how would I manage? How would I keep up with this Russian hero?

I checked with Tang, the ambassador’s resourceful butler, who knew everything about everybody and was probably in the employ of a half-dozen secret services. Any ideas? I asked. Tang considered my problem for a moment and then raced into the kitchen, where he found an oblong-shaped tray. When he returned, he proudly announced he’d come up with a solution to my problem. He would place vodka in shot glasses on one side of the tray, and water in similar glasses on the other. When serving Zhukov, Tang would make sure the vodka would always be on his side of the tray. Tang’s improvisation worked brilliantly.

When Khrushchev, Zhukov, and a few others arrived at Spasso House on July 4, 1956, promptly at 3 p.m., Bohlen greeted Khrushchev and, after a brief time, I approached Zhukov, introduced myself, showered him with compliments about his wartime adventures, and gently steered him towards a beautifully decorated backyard crowded with tables covered with hot dogs, mustard, ketchup, and beer. Acting like someone who’d missed lunch, Zhukov quickly devoured two hot dogs, seemingly in one bite, and looked around for a drink.

Tang made a timely appearance, bowed ever so slightly and cautiously extended his tray loaded with vodka…and water. Zhukov took one vodka and belted it back do dna (to the very bottom). Then he helped himself to another. I matched him drink for drink, vodka for water. All the while, we discussed his wartime exploits, which he was happy to do. Before long he consumed another hot dog, washing it down with a third and then a fourth vodka. I counted. After a while, Zhukov appeared to be getting a bit tipsy, but I, happy to report, remained a model of well-watered puritanical rectitude.

Not too far away, Bohlen and Khrushchev were deep in conversation and seemed to be enjoying their exchange. Zhukov suggested we join them, first gulping down another vodka. Holding me by the arm, walking slowly, perhaps because of the vodka, he made his way towards Khrushchev. When we got close enough, he stopped, pointed at me and shouted, “Nikita Sergeyevich, I have finally found a young American who can drink like a Russian.” Khrushchev, surprised but apparently pleased, shook my hand in a most friendly manner.

“How tall are you?” the Soviet leader asked.

I was thrown by the question but, after an anxious moment, answered, “Very tall, Sir, but still three centimeters shorter than Peter the Great.”

I smiled, not knowing what else to say or do. I remembered from my Russian history course that the Russian tsar stood six-foot seven-inches tall. (I was six-three; Khrushchev about five-six.) Khrushchev, hearing me compare myself to Peter the Great, burst into uncontrollable laughter. So did his colleagues. “Peter the Great!” he exclaimed. “That’s wonderful, simply wonderful.”

Another thought must at that moment flickered through his brain. “You play basketball, yes?” I was again thrown by his question.

“Yes, I love basketball.”

“Then you must know,” Khrushchev put a finger to my chest, “you must know that last night our best team, from Lithuania, won the national championship.” He glowed with pride. “The Lithuanian team is the best basketball team in the whole world.” He paused, playfully looking into my eyes for signs of approval. “You know, it could probably beat any basketball team in America.”

I’d followed Soviet basketball. It was good, and getting better, but it was not in America’s league.

“Well,” I replied, choosing my words with exquisite care, “maybe on a good night one or two of your teams might be able to beat an American team.” I hoped I had not offended him.

“No,” Khrushchev snapped, shaking his head, “no team can beat our Lithuanian team. It’s the best team in the world.”

Zhukov and other members of the Politburo, listening to our back and forth on basketball, nodded in puzzled agreement, but still looked uneasy about the flow of the conversation. Bohlen looked even more uneasy. I had just foolishly contested Khrushchev’s judgment. Worse, I didn’t stop. “With all due respect, sir, I truly believe that any really good college team, like Kentucky or Bradley, could beat your Lithuanian team.”

For an instant, I thought Khrushchev’s eyes flashed with anger—I cringed, expecting a storm. I had been told he had a fierce temper. On reflection, what in God’s name had possessed me? Who was I to engage in an argument with the leader of the Soviet Union—about basketball, no less? But, as suddenly as the storm clouds had gathered, they dispersed, and Khrushchev’s face broke into a warm smile.

“OK, then let’s compete,” he grinned, slapping me on the back while at the same time glancing at Bohlen. The ambassador, alert to any diplomatic signal, picked up the cue immediately. “What a superb idea, Mr. Chairman,” the ambassador announced. “I’ll discuss it later today with the president. Superb idea, a basketball competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, an international basketball competition. An excellent idea!” Bohlen smiled at Khrushchev, while tossing a quizzical look in my direction, as if to ask, what in the world are you doing?

In this way, Bohlen and Khrushchev brought a budding East-West squabble about basketball to a safe landing. In time, athletic competition between the two super powers did begin and flourish.

Shortly thereafter, preparing to leave, a relaxed Khrushchev again congratulated ambassador Bohlen on America’s July 4th holiday, and on his way out of Spasso House, he spotted me and said, “Peter the Great. That is great, simply wonderful.” We shook hands. He then got into his long black limousine and drove back to the Kremlin.

When I returned to Moscow a few years later as CBS’s bureau chief, I covered Khrushchev, and whenever he’d see me, he’d remember one of his favorite tsars and joke. “Ah, here’s Peter the Great.”

Marvin Kalb, former network correspondent and Murrow professor emeritus at Harvard, has just completed his third memoir on covering Russia during the Cold War. It’s called A Different Russia: Khrushchev and Kennedy on a Collision Course.

Back to the Table of Contents

Boot Time

By Jim Herrell

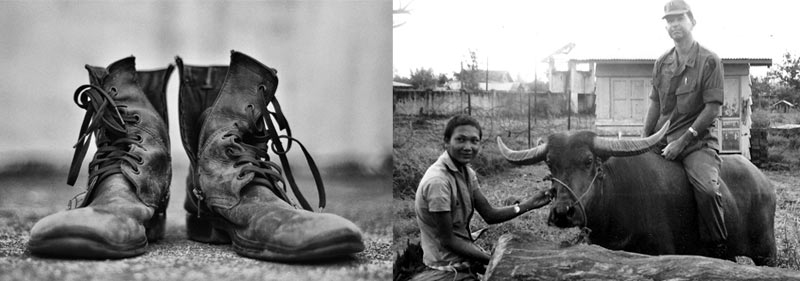

We loved going to the 2nd Field Force officers club, which was far larger than our hospital’s club on Long Binh Post, and served real food and drinks prepared by real cooks and bartenders, all of it served by beautiful waitresses from nearby villages. Plus, there was live music. Our club’s only amenities were booze, bar snacks, a 45-rpm turntable, and a small TV. We went to the 2nd FF club whenever we were allowed a few hours leave and access to a jeep.

The club’s members were real soldiers, not desk jockey officers like us. They wore combat fatigues; we wore comfortable olive drab uniforms. Its members—mostly Americans but some from other countries—actually fought the war, engaging the enemy, facing gunfire, mines, punji pits, grenades, mortars, and sweltering heat. We—two psychiatrists, a social worker, and a psychologist—did the best we could in the comfort of our fan-cooled offices to ameliorate the psychic wounds those soldiers endured.

We also loved the Aussies who one evening invited us to join them at their table. They—a captain and three lieutenants—were raucously funny, poetically profane, any one of them could outdrink the four of us, and they had cool accents. We spent the early part of the evening drinking, telling obscene jokes, and sharing fantasies about the waitresses. After our dinners and another round of drinks arrived, our hosts began telling us tales of their combat experiences, telling them with a self-effacing humor that minimized the dangers they had faced and the courage required to face them. With more time and drinks, their stories increasingly emphasized the horrors they’d witnessed, the horrors inflicted upon their comrades, the horrors they’d perpetrated, the horrors that continued to cause them nightmares. Nothing the Aussies told us was more shocking than stories from American soldiers we’d seen in our offices, but hearing it from a bunch of fun-loving guys with whom we were drinking, laughing, and checking out women was uniquely unsettling. Still, the Aussies clearly needed to share these stories, to admit to their fear and shame and self-doubt, and we were, after all, shrinks.

While describing a particularly horrendous experience, one of the young lieutenants began crying, soon joined by the other two, and perhaps by one or more of us. Seeing this, their dry-eyed captain, who hadn’t shaved in several days and had the look of an aged, grizzled veteran, although he couldn’t have yet reached his 30th birthday, said genially to his lieutenants, “It’s boot time, mates.” He removed one of his combat boots, saying to us, “It’s our tradition to drink from a boot at the end of the evening.”

After pouring the remains of his drink into his boot, he passed it around for the rest of us to add our remnants—a mixture, finally, of beer, whiskey sours, scotch-on-the-rocks, margaritas, and daiquiris. The captain took the first swig, then handed the boot to the lieutenant next to him. Not wanting to look like total wusses, we also partook. For the next few days, I monitored myself for signs of athlete’s tongue or some such thing, but I suffered nothing more serious than a hangover.

Arrival in Vietnam created an immediate sense of unreality. There was so little continuity to “The World,” as our troops referred to the US, that reality’s boundaries were shredded. Flying in, you saw a defoliated landscape pock-marked with bomb craters, looking like the lunar surface, and 24 hours daily there were sounds of gunfire, cannons, helicopters, rockets, bombs. Vietnam quickly became a separate reality, not the same reality in a separate place. This is, I suppose, true in most war zones. Under such circumstances, the emergence of new rules and new moral codes is inevitable, maybe even essential to survival.

I was 25 when I arrived in Vietnam. My experience as a psychologist had been limited to college students and military dependents. One of my first therapy clients in Vietnam was a kid, 18 or 19, a private E-1, the lowest military rank, yet already a combat veteran. Around his neck was a chain from which dangled three or four plastic vials containing objects I didn’t immediately recognize.

“What’s in those tubes?” I asked him.

“Fingers.”

“Fingers?”

“Fingers. I cut ‘em off Cong soldiers I killed.”

At the end of our session, he removed a vial from the chain. “This is for you,” he said, placing it on my desk.

He was, I understood, letting me know that I knew nothing of the reality in which he lived, and how little I’d ever know.

Back to the Table of Contents

My Wedding Trip

By Julie Oktay

Prologue

Prologue

In one of my Osher classes, we read and discussed short stories by various 20th century authors. For some reason, I was bothered by a story by Dorothy Parker called “Here We Are.” The story portrayed a young couple traveling by train to their honeymoon at a New York hotel. The story focused on the anxiety of both bride and groom anticipating their first sexual experience, the whole way avoiding the topic and instead talking about silly things: her hat, his attraction to one of the bridesmaids, etc. While I enjoyed the humor of the story, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Something critical was missing. As often happens in Osher, at the same time I was taking a memoir-writing class. The Parker story got me reminiscing in my memoir-writing class about my own wedding trip. This led to my writing about my own wedding, covering the same period as the “Here We Are” story: the wedding to the honeymoon, and trying to convey what was missing from the Parker story.

My Wedding Trip

We left my parents’ house in a suburb just north of Detroit, climbed into my bright red Sprite, and headed to our honeymoon in Northern Michigan. It was a warm evening in August and we drove with the top down. My new husband was driving as I navigated us through the suburb where I had been raised.

We began the trip talking excitedly about the wedding itself. It was, after all, the first thing we planned together, and we were quite pleased with the choices we had made. Greig’s Morning Song played as we walked from the house to the spot where the rabbi waited with my sister and my husband’s brother as bridesmaid and best man. After reliving the parts that had gone smoothly, our conversation turned to the glitches. My husband’s older brother’s two-year-old son had been parked next door to avoid any disruption during the short ceremony. Just as the ceremony was getting underway, we heard a child’s desperate voice screaming, “Mommy! Mommy!” behind us, followed by running steps, then shrubbery crashing, and then soft crying as our nephew settled into his mother’s lap. We sensed the attention of our guests moving toward the family drama, not returning to the ceremony until it was almost over. We laughed at the irony that we had spent so much time selecting the words that no one heard—except us! Then I shared how surprised I was when we cut the cake and discovered that it was white, instead of the chocolate I had insisted on. We speculated that my mother had actually ordered the traditional white and then assured me that the chocolate must have been the bakery’s mistake. We then explored some things that were puzzling to one of us. Why was he so late? It was the first time he drove to my parents’ house when I wasn’t with him, and he and his brothers got lost.) Why did I suddenly disappear right after the ceremony? (My aunt charged up to me the minute the ceremony ended, horrified that I had a run in my stocking. She pulled me to a private space nearby, insisting that I change them immediately!) Why did some of my relatives hug him warmly, calling him Steve? (He actually resembled my cousin Steve, who was not at the wedding.)

After this, we began to shift our attention to our honeymoon trip. My husband’s tone quieted, and I immediately sensed some anxiety. He explained that at the wedding itself, his older brother (who also had an American wife) told him that, in the US, the bride’s family traditionally pays for the wedding, but the groom is expected to pay for the honeymoon. His brother was able to offer only $50 to help with the honeymoon expenses. He explained to me that we would have to make that $50 cover the entire trip. I could see that he was quite worried that I would be disappointed, but I quickly reassured him that I didn’t care about having a fancy honeymoon as long as we would be together. He immediately relaxed, and we both settled into the drive.

By this time, we had left the city behind. First farmland and then tall trees lined the route. I found that I kept glancing over at him as he drove, noticing how smoothly he shifted through the gears, the car almost purred. He drove with confidence, but not at all recklessly. I could hardly believe this was happening to me! How was it that I got to be the girl in the red convertible next to this young man who looked like a movie star (Jean Paul Belmondo? Louis Jordan?). I felt like pinching myself. Was this really happening? He sensed that I was looking at him, and, without taking his eyes off the road, quickly glanced at me, a question in his eye. I smiled and then he smiled. We didn’t speak for some time. Later, when the traffic allowed, he took my hand. With his touch, I felt a rush of warmth running through me, exciting but also relaxing. I shivered with delight.

Something magical happened on that trip. As we drove through the warm, pine-scented Michigan night, it was as if I was emerging out of a chrysalis. Gone was the girl who had struggled to be herself in a family, a religion, and a community who wanted her to be something different. Now I was part of a new entity—a married couple. Suddenly I felt completely comfortable with myself, loved for who I really was. We were not just taking a honeymoon trip; we were starting a new life, starting to make choices that would define who we would be and how we would live as a couple.

Epilogue

After writing this memoir, I knew what was missing in Dorothy Parker’s story and why it had bothered me so much. She left out the current of communication, chemistry, and love growing in the new couple. And she left out the transformation from two individuals to an emerging couple now free to define their new life together.

Back to the Table of Contents

Mother Wanted To Make Her Mark

By Sean McCarthy

My mother grew up the youngest of the three children of a math professor at Ohio State. Her family wasn’t wealthy. However, I think she must have always had dreams to make her mark on the world beyond Columbus, Ohio. At age 16 she won a scholarship to attend Wellesley College back east in Massachusetts to study music and play piano and organ. At college she was exposed to the Boston Symphony and the intellectual and social atmosphere of Boston, including Harvard University, where she played piano as a guest with the student orchestra and eventually enjoyed an active social life. She was also exposed to the expensive accoutrements many fellow students and friends enjoyed, such as vacations on the Cote d’Azur in France, summer houses on Cape Cod and Nantucket Island, and luxury automobiles. I think she decided that she wanted to participate in this life style and wasn’t going to die poor, if she could help it.

After graduating college in 1937 my mother taught math at private girls’ schools in Denver and New York City. She then studied more piano and organ in New York, hoping to become a concert musician. However, in the early 1940s in the United States women were not welcomed into concert careers. In 1944 my mother married an impecunious divinity student who had a Harvard AB in music. After the war ended he decided to pursue a PhD in philosophy. However, a college professor in those days could not afford the expensive tastes my mother secretly coveted.

In 1959 with two children, ages 6 and 12, my mother was suddenly widowed. For 10 years she supported our family by teaching college math, first at the University of Pittsburgh and later Duquesne University. At age 53 she stopped teaching and plunged head first into buying, selling, and managing a few small apartment buildings in Pittsburgh. It was hard work and occasionally financially perilous. But she loved it and gradually built up capital.

In 1959 with two children, ages 6 and 12, my mother was suddenly widowed. For 10 years she supported our family by teaching college math, first at the University of Pittsburgh and later Duquesne University. At age 53 she stopped teaching and plunged head first into buying, selling, and managing a few small apartment buildings in Pittsburgh. It was hard work and occasionally financially perilous. But she loved it and gradually built up capital.

One of my mother’s business associates was Mrs. Leah Ross who owned Ross Real Estate brokerage in Squirrel Hill, the heavily Jewish neighborhood where we lived. Mrs. Ross’s real name was Rossi, not Ross. She was Italian, not Jewish, but I don’t think any fuss was ever made about her misleading name one way or the other. With Mrs. Ross’s occasional help my mother progressed in her real-estate investing. During her career my mother bought vacation houses in Nantucket and later Naples, Florida, bought a Mercedes station wagon she could use for hauling furniture, and took a few vacations in Europe, including one to Antibes on the French Cote d’Azur. She also played bridge from time to time, and for a number of years played piano regularly with other amateur musicians in chamber music sessions at our house in Pittsburgh.

One Christmas holiday morning I was home for a visit, enjoying some breakfast cereal and tea, and reading the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. My mother interrupted my pleasant reverie: “Mrs. Ross is going to Florida for the holidays.” By then Mrs. Ross was in her 80s and retired. She had sold Ross Real Estate to her children, who had made her promise to stop buying more real estate.

“Uh huh,” I replied.

A few minutes later, “Mrs. Ross is going to Florida.”

“So? What about that?” I replied.

“Mrs. Ross is worried that something might happen to her in Florida.”

“So?”

“Remember that property I told you I wanted to buy with Mrs. Ross? The one where she would own one-third and I would own the rest?”

I put my newspaper down. I did remember hearing about this, but I foolishly thought the idea had died. Mrs. Ross was not supposed to be buying more real estate.

“What happened? Did you buy that property with Mrs. Ross?” I asked.

“Yes, but only my name is on the deed, and Mrs. Ross wants something in writing showing her ownership in case something happens to her in Florida,” my mother responded.

My eyes rolled. “I can draft something, but it won’t be legally valid, unless you file it with the Recorder of Deeds.”

“Oh no, we can’t do that. We would have to pay a tax to record it. Just write something so Mrs. Ross can sleep better,” my mother pleaded.

I told my mother that I would write something describing her percentage ownership with Mrs. Ross and their relative responsibilities for expenses, but she wasn’t to tell anyone who wrote it. I was afraid the Bar Association might find me guilty of malpractice.

“Good. Here. Write on this. Keep it short.” She handed me a three by five-inch notecard. I grimaced, but wrote about four sentences that seemed to sum up their deal. I left space for signatures. I didn’t add language about warranties, indemnities, and other stuff that fills out most legal agreements. I handed back the card.

“This is good. Can you make it shorter?” my mother asked.

“Are you kidding? It’s less than a hundred words.” I emphatically demurred.

Mrs. Ross had an uneventful trip to Florida, and a few years later these two conspirators sold that building for a profit. I don’t think Mrs. Ross’s children ever found out.

In 1998 after years of searching for a vacation house to replace the one she had previously owned in Nantucket, but in a place she enjoyed and that would entice her children and grandchildren to visit her, my mother bought a condo in Naples, Florida. It was three blocks from a beautiful white sand beach on the quiet Gulf of Mexico, a few more blocks south to the Naples Fishing Pier, and near downtown restaurants and shopping. My wife and kids loved visiting her there. So did I.

By this time my mother had sold all her rental properties in Pittsburgh, but she was not ready to retire. In 2000 at age 84 my mother bought the “Tipsy Seagull,” a Tiki bar and grill with thatched roof, surrounded by palm trees, and located on a canal in the less-developed east side of Naples Bay. It sat on wooden piers four feet above hard packed sand with a deck facing the canal and wrapping around to the right to overlook the parking lot on the entrance side. Inside under the exposed wood beams and thatched roof a polished pine wood bar stretched across the center of the room and faced the canal. A few people could sit in front of the bar and at the narrow shelf on the three-foot-tall wooden wall looking out on the canal. Frame windows swung up and out from the wall and over a six-foot-wide deck where five small boats could dock.

The liquor license allowed for the full bar and for sales of beer to take out. Not long before the Tipsy Seagull had been a biker bar. Now it was a neighborhood bar not yet frequented by the tourists swarming the west side of Naples along the Gulf Coast.

My brother tried to dissuade my mother from buying the restaurant. He felt she was too old to run a bar and grill. She would also be violating the promise she made to herself in 1958, when she owned and operated her first business, a beauty parlor, for 11 months. That had not gone well, because my mother didn’t have a beautician’s license and had to rely on others who did. My mother had resolved: “Never buy a business you know nothing about.”

I thought the bar and grill had potential, and my mother was going to hire a younger man, in his 40s with restaurant and bar experience, to operate it. My mother wanted me to invest in this venture, something I had previously declined to do, not wanting to be financially as well as emotionally involved in her business ventures. However, she had always done well with her real-estate investments, and I decided I wanted to participate. My mother was short of cash at the closing, and I wound up exceeding the investment limit my wife had tried to impose.

Much of the value in the bar and grill came from having a liquor license. We paid the owner of the Tipsy Seagull to transfer the license to my mother, but the transfer had to be approved by the Florida State Liquor Control Board. My mother had to attend a hearing in Tallahassee. At the hearing one of the members of the liquor control board, probably noting that the applicant was an elderly white-haired lady, tried ineptly to ask the question that must also have been on others’ minds: “Mrs. McCarthy, can I ask why you want to buy this bar?” To which my mother shot back, “To make money, of course.”

She got the license. The investment did well for a few years, until the operator she hired decided “to pay himself first” and stopped making his operating lease payments. My mother wasn’t used to dealing with personnel problems, which essentially this was. After failing for a number of months to get any payments from the operator, she decided to let the operating lease expire. Regrettably she did not inform the operator that she would not be renewing his lease until only 10 days before it expired. The operator was surprised and wasn’t happy. On the last day of the lease he pulled out most of the kitchen equipment and, although we couldn’t prove it, poured gasoline around the pump that we had installed to serve boaters and called the Florida Environmental Protection Agency.

After that it took us seven years and some costly environmental consulting services to satisfy the Florida EPA the property was cleaned up and finally to get a buyer. Fortunately, my mother and I broke even on the capital investment we had made. We both learned a lot owning the Tipsy Seagull. Unfortunately, my mother died four years later.

I think real-estate investing kept my mother alive and allowed her to live a long life. She especially loved the buying and selling of properties. Her math ability let her quickly calculate what was a good deal and helped her make an even better one as she negotiated. The profits she made in real estate enabled her to achieve everything on her bucket list except impressing Harvard with her gift, but almost no one can do that.

I asked my mother where she wanted to be buried. There were a few options. Her answer: “I want to be buried where people will come to visit me.” So she is buried a mile from my brother in Cary, North Carolina. The bronze plaque on her grave reads: “Harriet Rasor McCarthy, 1916–2014, Mother, Musician, Teacher, and Real Estate Investor.”

My mother didn’t die poor and I think she did make her mark on the world, but I wish she had spent more of her last years enjoying the fruits of her labor and the society of others. When she learned at age 97 that she had terminal cancer, she was shocked and I think disappointed that she would not achieve one last thing on her bucket list: to live to be 100 years old. However, after a short time, she accepted, as we all must, that there is an end to life, a final sale whose benefits we will not enjoy.

Back to the Table of Contents

My Mother’s Hairbrush

By Sugie Weiss

Our mother, Mummy to the five of us, was not one to spend a great deal of time styling her hair. She did go to a local beauty shop every few weeks to have her hair set. She always took me with her as this was in the early 1950s and I was not even 10 years old. I can still recall the astringent odor of hair dyes and permanent wave lotion wafting through the small shop. There was only the owner and my mother when we went. I would sit on the floor using a magnet that the owner had given me. I diligently gathered up all the bobby pins, curlers, and hair clips that had fallen to the floor. There was a clicking sound as the magnet attracted and grabbed the metal items.

My mother enjoyed catching up on the hairdresser’s news and shared news of all of our lives as well. After her hair was styled and we were on our way out I was always given a lollipop and thanked for my “work.”

On one occasion I recall a conversation about the hairbrush that was moving gently through Mummy’s wispy hair. My mother inquired where the hairdresser had purchased it and was delighted to hear that it came from the Fuller Brush Company, a company established to offer household items, best known for its door-to-door sales by the Fuller Brush Man. My mother was a devotee of the products peddled by the Fuller Brush Man. She had always bought her cleaning brushes from him, but never a hairbrush.

The next time the Fuller Brush Man arrived with his suitcase of scouring brushes, kitchen utensils and hairbrushes, Mummy was delighted to see the clear-plastic-handled spiral hairbrush, identical to the one she had so enjoyed at the beauty shop. The Fuller Brush Man carefully filled out her order slip and promised to return within 10 days with her purchases.

Good to his word the Fuller Brush Man returned with each item wrapped in brown paper. Mummy took great pleasure in using that brush on her own hair and on mine after a hairwash. She used it for a number of years until one day, after I had done something egregious, she marched me into her bathroom and told me to sit down next to her on the edge of the tub. Mummy never got upset with us, so whatever I had done was serious. To make her point she picked up her beloved hairbrush and brought it down on the tub’s edge, hoping to make her point crystal clear to me. Suddenly her brush was in two pieces. With the breaking of the brush her anger quickly dissipated and we both burst out laughing.

Back to the Table of Contents