Travel with Osher!

Fall/Winter 2022

Volume 32, Edition 2

Contents

The Man in Bazarov’s Hat

By Saul Lilienstein

Sometimes when I am standing on the platform of a New York subway station and the people are casually lined up at the platform edge waiting for the next train, I imagine seeing there a tall young man of 21 or 22, slim and silent, with sloping features on his dark, poetic face. An old French hat, soft blue-grey wool and shapeless, lies easily on his head. The man’s name is Larry G. and I know that he would be over 60 by now, but in that momentary flash he is still a young man. This was the way he looked when I met him 40 summers ago, and I have never laid eyes on him since.

Sometimes when I am standing on the platform of a New York subway station and the people are casually lined up at the platform edge waiting for the next train, I imagine seeing there a tall young man of 21 or 22, slim and silent, with sloping features on his dark, poetic face. An old French hat, soft blue-grey wool and shapeless, lies easily on his head. The man’s name is Larry G. and I know that he would be over 60 by now, but in that momentary flash he is still a young man. This was the way he looked when I met him 40 summers ago, and I have never laid eyes on him since.

It was my first real job and the first time away from home. A kitchen boy in summer camp. Though only a few months past the age of the older campers, by the beginning of the second week I was promoted to the job of waiter and moved into the waiters’ bunk. It was an army-style Quonset hut with six cots lined up on each side and a toilet at the back. I knew only Eugene, a face remembered from the neighborhood. We exchanged words of recognition. I walked by him with my trombone case and duffel bag, and arranged my things on the vacant bed, four down on the left. The first bed on the right was where the head of our group slept. Larry G.

He was the oldest waiter and the smartest. His corner of the bunk had been turned into a personal library of Dostoyevsky, Dickens, Marx, Engels and a variety of books on social philosophy and contemporary history. Most nights he read, supplementing those books with Jack London novels from the camp library and accounts of New England life found in the library of a nearby town. He gave the other waiters borrowing privileges, but we hardly ever took him up on it. One or two evenings a week Larry would put down the book in his hands and begin speaking of what was on his mind, and the bunk would turn silent and listen to him. That was how I heard the story of his hat.

He called it Bazarov’s hat and he never took it off except to go to sleep. During the war of armies, White and Red, in northern Russia, a Trotskyite named Bazarov slit the throat of a Czarist sympathizer and took the dead man’s hat as a trophy. By 1938, Bazarov was starving to death in a Siberian prison. That hat was his only link to the glorious time. I no longer remember how it was that the hat came into the possession of Larry’s father, but now it was his son’s. He wore it every day and in every place. Late each night when Larry took off the hat, it was a tacit signal to the rest of us to turn out our lights and go to sleep.

On the fifth night, he put down the book and began speaking of the necessity of socialist revolution for western Europe. In a patient, step-by-step explanation, he quietly stated the case for a Soviet takeover. A sudden, countering thought came to me: “But you wouldn’t trust the Russians, would you?” I called out. “Look what happened to Bazarov.” Larry stood up and walked over to the bed I was sitting on.

“I hear you are studying to be a musician. Can you sing a major scale?” “Yes, of course.”

“Stand up then. Sing.” I never got past the fourth note. “That was out of tune,” he said. Then, he struck. I didn’t know that a fist made such a sound when it ripped into a face, or that the taste of blood was pungent in the throat. I had never been hit before.

“Start once more. Slowly this time—and be more careful with your intonation.”

I was stunned by my acquiescence, but his words sounded as if they came from another and totally reasonable person. I began to sing the scale. The third note was flat, but it was too late to make a correction. His swift moving knee caught me in the stomach. I lay there, nauseated and isolated, unable to speak or cry, going over and over again in my mind the notes of a major scale.

Every third or fourth night, the book would close and another political lesson began. If I kept to myself, pretending to sleep, it did no good: “You’re so quiet tonight,” he would say. “What do you think about that?”

There was no escape. And so, I took to finding fault with his reasoning, challenging him cautiously, as one sucks cold air through a decaying tooth to test for pain. Each time, some humiliation to myself or desecration of personal belongings would follow. Only the trombone and my study scores were left undisturbed. Larry G. had a respect for music that bordered on the mystical. If I could have wrapped myself in a scroll of Beethoven symphonies I would have been safe from him.

Eugene from the neighborhood gave advice. His face was pained when he spoke and the voice filled with apology: “Just nod in agreement. Don’t bug him, don’t cross him, don’t argue. Please.”

That was the extent of his help. As for the others, a blindness took over. The day was for work and playing ball. The problem never came up. I was glad to be one of them on afternoon swims, to curse out the kitchen boys or boast about girls.

In this way the summer continued. There was a field of tall grass to walk through and when the top blades slapped at my face I took the sting as a deserved response for my weakness, calling out curses of impossible revenge as I moved along. And there was a girl; a senior camper who knew of secret places. I don’t remember her name, but I can still sense her trembling breath against me and I see her eyes watching me, moving closer to mine. I told her nothing.

Midway through the summer the campers were presenting H.M.S. Pinafore. There was no one to play the villainous Dick Deadeye and I was enlisted. Every evening’s rehearsal meant two hours away from the Quonset hut. Then the camp turned quiet and the final scene of the day would play itself out again. On opening night, Dick Deadeye roamed the stage with more stealth and anger than W.S. Gilbert had written into the lines. The little children of my waiters’ station stood in front of me during the last ensemble, singing “his sisters and his cousins and his aunts,” turning and tugging at my sailor’s outfit.

“We know who you are!” they laughed.

Dick Deadeye was all they got in return. I was proud of my performance. At the final curtain, scanning the audience, I quickly located the one person wearing a hat and savored a victory over him. Backstage, Larry spoke to me about the performance.

“I noticed how you held character to the very end. That was a fine piece of acting,” he said.

At that moment, I loved Larry G.

The camp had an old Italian chef, Mr. Sidoli, who sang excerpts from Donizetti and Verdi as he worked. I realize now that his sense of the style was perfect and his small voice remarkably pure, but then it was just an old-fashioned sound to my ears. Larry knew better.

“What did you think of Sidoli’s Una furtiva lagrima?” he asked.

I told him that the old man sang through his nose. That night a punishment was conceived to fit the crime: two of his lieutenants held me down while Larry stuffed my nostrils with soap powder. He cupped his hands over my mouth until I was forced to breathe in the soap.

One week before the end of the season a waiter took ill and had to be replaced. The new boy moved slowly and had a bovine softness to his body compared to the bunch of us who had lifted heavy trays for six weeks, who had run and cursed at top speed through July and August. The evening’s discussion was on the plight of the Eskimo. Larry spoke persuasively about the ruination of their culture at the hands of our government. The new boy mumbled something about the Eskimos not being civilized. Larry’s calm voice paused for a moment and then continued, calmer still:

“And why do you think that?”

The boy was taking clothing out of a duffel bag, folding things carefully on his bed as Larry walked over to him.

“Well, for one thing, they can’t even speak English.”

Larry’s fist caught him in the neck as he was turning. The new boy gasped for breath and then threw up over his folded underwear. I moved away from the scene and for the first time in weeks felt safe in my bed. It was two years before I would discover Orwell’s 1984 and read the page where Winston Smith stares at the rats in the cage at his head, calling out, “Do it to her.” In all the years gone by, no passage in modern fiction has ever affected me more.

There in the New York subway, a young man in a soft woolen hat … We catch each other’s eye and break into smiles of recognition, I in my 50s, he still 21 or 22. We talk about that summer and of our lives since then, of good and evil unresolved, and of the potential for violence in all of us, even in all the good men. And then the train rushes into the tunnel, and I push the bastard onto the tracks.

Back to the Table of Contents

An Historic Figure

By Bill Lewis

On August 6, 2022 the National Football League (NFL) held its initial preseason game of what will be its 103rd season. The “Hall of Fame” game, as it is called, is less known for football and more for the Induction Ceremony for the newest elected members into the NFL Hall of Fame. This year, eight individuals were bestowed the honor to enter the Hall, which now has 362 members, and includes the giants of the game, Super Bowl players, All-Pro players, owners, and people who were instrumental in making pro football the world’s most watched sport. This year history was made when the Hall welcomed its first on-field official, Art McNally.

Art McNally, now 97, was an NFL Referee from 1959 to 1968, when he became the full-time NFL Supervisor of Officials, a post he held until 1991. During that dynamic growth period in the league, Art was credited with developing the first formal training and evaluation program for NFL officials, and in 1986 he implemented the first use of “instant replay” into the game, which is indispensable today. Art believed that the NFL should employ every tool available to help officials make the correct call. As was noted in his induction tribute, Art always said that “if no one notices the officials, then they are doing a good job, and that’s best.” Indeed, the NFL Command Center in New York City, where all replay reviews are conducted, is named after him.

Art McNally’s professional accomplishments aside, he was a fine person, who set high standards for everyone around him. I would know because Art was my offensive and defensive position coach during my junior and senior years playing high school football at Central High School in Philadelphia in 1962–63. Art could not accept the Head Coaching position for our football team because he was normally selected to referee the nationally televised Thanksgiving Day game between the Detroit Lions and the Green Bay Packers, as well as other potential scheduling conflicts. For example, all NFL officials assigned to a game must be in the host city at least 24 hours before kickoff, which made Art unavailable for the traditional Central-Northeast High School Thanksgiving Day game, which has been played since 1892.

I was almost moved to tears by the tributes given to Art McNally at the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. I am so proud of his accomplishments, and the fact that such a fine person was being cited for his significant accomplishments over his nearly 60-year career with the NFL. I will always remember how calm he was under pressure, how well he taught us the game of football, and his recollections about games he had refereed involving football legends like Jim Brown, Paul Hornung, and Lenny Moore. In writing this tribute to him, I wanted to honor him for all of his fine qualities but more importantly for the positive impact he had on the young men he coached, and the positive impact he made in their lives. I am sure I am not alone in saying, for all of those men, “You made us proud, Coach Mac!”

Back to the Table of Contents

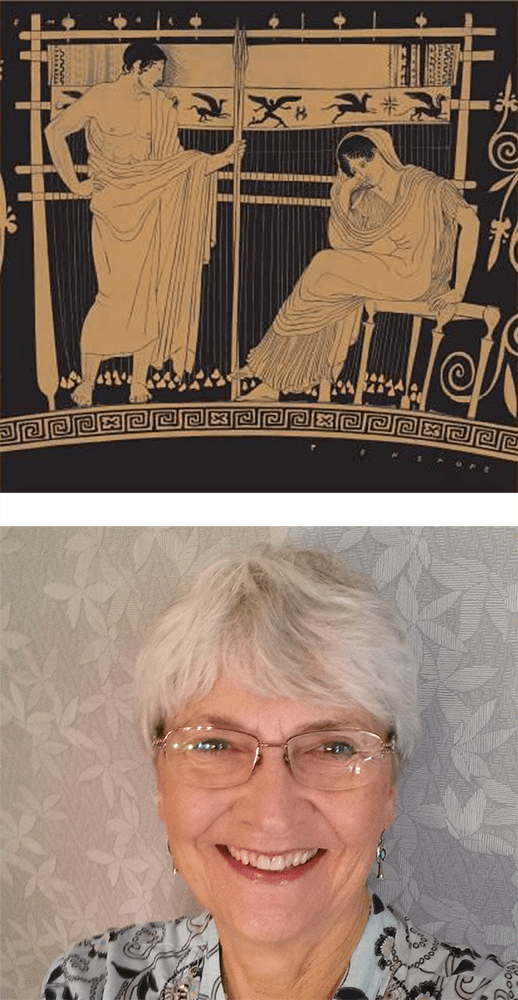

Penelope

By Linda Middlestadt

I will become a name for faithful,

Though here I sit on a rock above the sea,

wine-dark as the poet will say,

old and lonely.

He has gone again,

like that first time,

with good purpose, high-minded,

how he pretended to sow a field with salt

but gave in so readily

to the warrior’s call.

Off they went for ten years

of sterile battle,

and ten years of straining for home, or so he said.

And me alone, raising our son,

minding our servants, our fields,

with only old men

and women around me.

Then came the suitors, haughty,

pretending desire in their greed,

and why should I choose less than I had,

who was king of my land

and my son and my bed?

So every day weaving calmly, placidly,

and every night unweaving

with unseeing eyes,

almost wishing some

besotted male

could see through my ruse.

Him I might marry!

After some faithless maid

undid me,

I chose such a test of strength

and skill,

sure to outwit them again,

when in burst some creature,

wild and unclean,

violent and vengeful, bringing

their drunken feasting to a swift

and bloody end.

Did he expect me, forced to be so patient for some twenty years,

circumspect, so the poet will say,

to clasp his clawlike hand

and rejoice?

Later in the night, only then could

I accept him

in the way we are all bound

to forgive our men.

Now he and my son

wander together

And I have traded (wasted) my life

for a few nights of passion

and one fatherlike son,

I could (should) have been

a poet.

Back to the Table of Contents

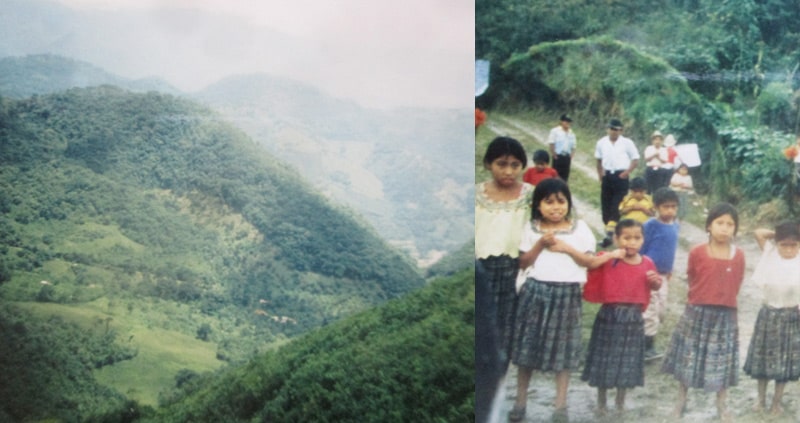

High True Peace Under Five Roofs

By Randy Barker

While rain fell outside much of the time, five roofs kept us dry and strengthened the high true peace that embraced us inside. We were two men, four women, and three teenage girls visiting Sepalau for several days in the summer of 1993. Sepalau was a community of about 30 Mayan families situated in the mountainous north of Guatemala, a region known as Alta Verapaz or “high true peace.” Ours was a “sister parish” visit from Corpus Christi parish in Baltimore. When our pickup truck reached the village, Patricia, a pastor of Payne Memorial AME church, said memorably, “I have looked to the hills from whence cometh my help.”

Best of all, I recall the welcome we felt under the roofs of five village huts and community buildings.

First roof, over the school. The school was a cinder-block building with a corrugated metal roof, a roof that amplified the sound of the rain. There the entire village crowded in to meet us, to the beat of a huge marimba that several men were striking. Almost immediately, children took our hands and we entered the first of three nights of “getting to know you” through dance. At one point, I danced holding a small cassette recorder. To this day, I return to the lovable magic of that dancing any time I play my tape. By night, we danced in the school, and by day we learned about the community…from wall posters on which the kids had drawn quetzals and ceiba trees and from presentations such as skits about a dead person being carried on a plank or a man selling his horse. Reciprocating, we sang from the American song book such standard fare as “Amazing Grace,” “The Hoky-Poky,” and “Tis A Gift to Be Simple.”

Second roof, over the one-room hut of Pedro Rax. Here all nine of us slept each night, warm and dry under a thatched roof that repelled rain well. A drawing in my journal shows each cot and who slept on it. I describe two surprises in the morning: chickens who had roosted under our cots during the night, coming out to wander around; and the arrival of Luisa with a piece of burning firewood that was placed on the dirt floor to light up some dry wood. The smoke of this cozy fire curled up to and through an opening in the center of the roof.

Third roof, over the hut that had been fixed up as a place for meals. The hut had a wall separating a table and benches from a kitchen space. The typical meal consisted of a chicken broth with corn in it and warm sweet beverages with coffee or herb flavors. While we nine sat on the benches to eat, servers and curious villagers stood beside us. I recall well, hanging on the wall behind me, a roundish sling, which I realized contained a sleeping baby.

Fourth roof, over the “ermita” or chapel, another cinder-block building. Here each day we celebrated “el servicio de la palabra” (the service of the word) for one or two hours. Most of the service was conducted by lay ministers, in the Mayan tongue Quekchi. Only a few people in Sepalau knew some Spanish, meaning that we did our best to pick up useful words in Quekchi. During services, we learned to say often, with everyone, “benti-osh a Dios” (Thanks be to God). Memorable are the out-crying of prayers, at first mainly from men, then from women…in a space fragrant with incense. At the first service, we played recorded singing from Corpus Christi, and in Spanish translated to Quekchi, I voiced greetings from our parish to theirs.

Fifth roof, over the house of Mariano, a leader in the village. Mariano invited us to make tortillas the way each family does over the fire in their hut. On a large flat stone, we each rolled our palm over a handful of fresh corn kernels to make a mash, then shape it into a round flat tortilla and put it into an iron pan to cook. The corn is dark purple, a strong-tasting and high-nutrient variety that is the mainstay of the Mayan diet. On a cot in his house, Mariano, knowing I was a doctor, asked me to examine his daughter Luz. She held on her lap a baby less than a year old. From our translator Raoul, I learned that since the baby’s birth Luz had been bed-bound and very swollen, something I could easily see. She felt feverish to me and had abdominal tenderness. I decided she had a mix of either post-partum kidney or heart failure and an intra-abdominal infection. Helpless to do much, I gave to her our group’s entire supply of Cipro and instructions. At my suggestion, the villagers said they would try to get her to a doctor in the valley as soon as possible.

Therein my story of appreciating much about Sepalau, under five roofs. Rain fell part of every day and night during our visit, and those roofs over our heads brought comfort and closeness.

In addition to rainfall, the village was often over-covered by clouds, so that we could just make out the hut or building we were looking for. After hearing the Gospel reading at Mass today, March 13, 2022, which described the transfiguration of Jesus in the clouds, I found myself, 30 years later, imagining those clouds over Sepalau as messengers of a transformative gift we were receiving from the people of Sepalau, a gift that is still present.

Back to the Table of Contents

Los Bandidos

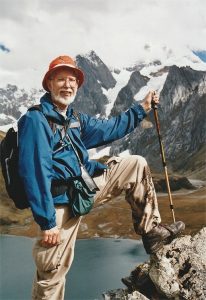

By Jim Herrell

On July 3, 2004, darkness, snow, and a pack of bandidos descended upon our campsite in the Huayhuash Valley, 14,600 feet high in the Peruvian Andes.

My companions on a planned three-week hike were five Americans, including Skip, Julie, and Louie with whom I’d hiked in the Himalayas five years earlier, plus another man and woman; Yvette, a Peruvian woman Louie knew from previous hikes; and a Peruvian crew who served as guides, cooks, and donkey wranglers. We had just finished the hardest day of the trek, a day on which we’d walked farther and reached a higher altitude (over 16,000 feet) than on any previous day. Worse, it had been cold, with rain in late afternoon and snow beginning around sunset. Eager to reach camp before dark, our crew had urged the slower hikers to put our backpacks on the donkeys so we could walk faster. We did, but our rain gear was in our packs, and the donkeys were far ahead when the rain hit, so we stragglers stumbled into camp late, cold, soaked, and miserable.

After changing into dry clothes, I was headed for the dining tent, where our crew was cooking dinner, when I thought I heard firecrackers. Suddenly, six or so bandidos emerged from the darkness and snow, shooting rifles into the air, herding in front of them two groups who’d been camping farther down the valley – four Israelis, three Aussies, and their crews. Pointing their rifles at us, the bandidos ordered us all to lie face down on the ground, hands on our heads, and threatened to shoot anyone who looked at them. We never knew their exact number, or what they looked like—I could see the man in front of me only from the waist down. Speaking harshly in Spanish, with Louie translating, the bandido chief told us they were not bandits, but revolutionaries opposed to the current Peruvian government, multinational corporations, and the American president (Dubya at the time, so we gringos signaled our agreement). They were robbing us only to support their cause, he said, not to enrich themselves. Revolutionaries, bandidos, we didn’t care—they had guns, which, in a blatant and spectacularly successful attempt to terrorize us, they occasionally fired in our general direction, sometimes close enough that we could feel dirt and snow kicking onto our faces from where the bullets hit.

After the opening oratory, a couple of bandidos monitored the crews and others escorted the Aussies and Israelis back to their camps, taking Yvette with them as an interpreter, a single tear rolling down her cheek as she left. With Louie again our intermediary, two bandidos interrogated us in the dining tent, demanding to know our professions, and what work our parents and children did. We knew we had to be truthful, at least insofar as truth was verifiable. If we lied about what we had in our tents, our lies could be discovered, undoubtedly to our disadvantage, but lies about our jobs and families couldn’t be immediately checked. Fearing they might want to hold us for ransom, we minimized our occupations and those of our parents, living or dead, and pretended our children were penniless college students. I admitted to being a psychologist but not to being a government employee—I didn’t believe they were revolutionaries, but who knew for sure, and I didn’t want to be associated with “government,” mine or theirs. After hearing all this, the bandidos told us we could go free if we gave them $8,000. Louie explained that, except for Yvette, who had no money, we each had brought with us exactly $200, including tip money for our crew, totaling $1,200, which they agreed to accept.

Our money in hand, the bandidos ransacked our tents. They took all of our cameras. I had Cipro in case of Atahualpa’s revenge and Diamox for altitude sickness, which they took. They took my flashlight and headlamp but not the 15-pack of AA batteries, my toothbrush but not my toothpaste, and my trail mix. They took clothing from all of us—my heavy-weather gear, Louie’s boots, every pair of Jerry’s pants except what he had on, and in addition to other items from Julie, who’d stepped in a mud puddle earlier, they took the clean sock she’d removed but not the muddy one.

During the interrogation and ransacking, everyone had been compliant and uncomplaining, everyone but me, anyway. During the winter, I’d tried downhill skiing for the first time, and, hoping to create the illusion of being an actual skier, I’d left the lift tickets on my windbreaker. When the bandidos took the jacket from me in the dining tent, I told Louie to ask them for the lift tickets, a feeble attempt at humor eliciting a sharp chastisement. Later, I said, “Tell them I want a receipt,” not entirely a joke, because on our Himalayan trek we’d heard that bandits gave their prey receipts to show if later set upon by other bandits. “Shut the bleep up, Jimmy,” Louie hissed.

My class-clown behavior was not the only bit of noncompliance. During the interrogation, Skip and Julie did not tell the bandidos about their “greenwipes,” $300 hidden among toilet paper and packages of hand wipes. Their deception was not discovered, and the money came in handy later.

After about an hour, the bandidos returned with the unharmed Yvette, freed our crews, ate our dinner, told us to continue our trek, warned they’d be watching us, and disappeared into the darkness. They’d hurt no one.

We quickly agreed our trek was over, so we’d get the hell out of the Andes, get back to Lima, and go home. Two tough hiking days later, we reached a village with electricity and a telephone. There, we learned from other trekking parties who’d also been robbed that the bandidos had been looking specifically for us, asking every group if they’d seen the Americanos, presumably figuring we’d have the most money.

With the Israelis who were robbed with us and some Brits who’d been robbed earlier, we hired a bus to take us out of the mountains, paying for it with the secret stash of greenwipes. Our ride proved unexpectedly harrowing. We started over two miles high and descended to nearly sea level. The winding, unpaved, boulder-pocked road, recently blasted from the side of a mountain, was scarcely wider than our bus, with infrequent wider spots to allow passing, and basically straight down on the passenger side—if the bus drifted a couple feet too far right it’d be all over. We rode in the dark, which on the one hand was scarier because we (but more importantly, the driver) couldn’t clearly see what we were dealing with, and on the other hand less frightening because, well, we couldn’t clearly see what we were dealing with. In a meaningful way, we were in as much danger on the bus as at the hands of the bandidos. Our driver, who before departure had crossed himself several times at a village church, got us down safely, but in Lima, we’d learn the horrific fate of a less fortunate recent busload.

During the head bandido’s peroration about their revolutionary aims, I realized this would be a great story to tell if I lived through it. I’ve told it often, and I’m usually asked if I had been afraid. Yup, but I didn’t feel the fear, I just knew it was there, visualizing it as safely encased in a plastic sphere about half the size of a ping pong ball embedded in the back of my brain. While lying in the snow dressed for the warm dining tent and not for the weather, I was far more aware of being wretchedly cold than of danger or fear. I never seriously thought I’d die, mainly because I’m really good at denial, but partly because we’d been warned about bandits before the trip, so I assumed their intention was robbery, not murder.

While listening to the bandido chief’s harangue, we each developed our own Plan B. We’d cooperate up to a point, but if the bandidos got too rough or molested the women or started shooting us, we’d fight back. They never crossed those thresholds. We’d later learn how lucky we’d been, and how much we owed to Yvette and Louie for their grace under pressure while managing our interactions with our uninvited dinner guests. In September, Yvette notified us from Peru that bandidos had recently killed one trekker and wounded three others when they resisted.

Back to the Table of Contents

My Favored Library

By Judy Ashley

Only one building in my life symbolizes “comfort” and “home”—the old Lansing, Michigan Public Library. Located six blocks from our house, it was the first library I visited. On Friday nights, my parents, sister, and I walked together to the library to spend some quiet time.

The first section visited inside included children’s books, and I felt so sophisticated and smart in my small chair in the adult library. When I finished looking at the selections there, I tiptoed behind the gigantic oak checkout desk to a special room. The flooring in that room included clouded white glass panels including steps up to a mini-mezzanine. That extraordinary décor felt so slick and my soles clicked with a fantastic sound on the glass.

The very first two books in my life checked out of the adult library were shelved in the glass floor section. One was a book for parents to give to children to help them understand the complexities of childhood. I do not recall my parents scrutinizing my choice of books. It was in that book where I first learned about sodomy.

The second book was a novel by Australian writer, Nevil Shute, The Legacy. I devoured the story about a group of women in Malaysia during WWII who were marched for dozens of miles without food, water, or rest. Regardless of whether I understood all of the story, it was my #1 favorite book for years. It was made into a movie, A Town Like Alice. When my daughter became a college student, one summer we read the book aloud. She enjoyed the story very much too. I even joined the Nevil Shute Fan Club. I treasured the discovery of the author as one of my first adult books checked from the library.

Another highlight of Friday night visits included a game, “the card catalog game.” I opened a random drawer, selected a card with words I could read, such as churn or giraffe. Copying the numbers from the card, I then hunted for the book. Soon I knew many tricks about book hunting.

Another activity included sitting at the tables in the newspaper section. The newspapers were stored in special wood rods, split in the middle where an opened newspaper would be placed, and clamped shut. I sat and turned the pages, so mature.

When we left the library to walk home, we climbed around the huge columns outside the front. We ran up and down, jumping, and counting the many steps.

The Public Library in my childhood meant comfort and excitement. Fortunately, during a city renewal project, someone realized the value of the building and it was repurposed. When visiting the city occasionally over the years, I stopped and paid respects to the old place. The columns required too much balance, but I walked up and down the steps counting. A single building—the old library—holds incredible secrets of many, many hours spent there.

Back to the Table of Contents

My “Math-Squitos” Lesson

By Sam Dowding

It was the first year of my Economics and Business Administration degree at the University of Guyana, and I was taking a required advanced mathematics class. The course was similar to one that I had taken, and failed, at the GCE Ordinary level just a year before. I was apprehensive.

Throughout my first year, classes were all held in the evenings to accommodate participation by working students, who at that time comprised most of the student body. This was only the second year that students had gathered on the new but modest campus, which sat on land that was previously a sugar plantation. In 1970, the campus was still surrounded on three sides by thriving sugar cane fields and indeed the requisite (and traditional for Guyana) canals that irrigated the crop. No surprise therefore that the mosquitos, so ubiquitous across the Atlantic coastland of Guyana, were ever present at night on our campus located in the middle of a cane field.

One night in my math class, they were particularly vicious. Some students tried smoking cigarettes in vain hopes of the smoke distracting the menace. Alas! We resorted to smacking those that buzzed around our ears, or worse those that landed, of which we only became aware when they had already sunk their proboscises into our flesh and had drawn blood. Successfully smacking those left blood splat stains on our hands and clothes. It was no surprise that we were accordingly paying scant attention to our class.

Observing the general distraction from his class, Professor Chunilall taught us a valuable math lesson that night. “How many mosquitos have each of you killed so far?” None of our answers exceeded 10. Among the 15 or so of us in the class, we had not even eliminated 150 mosquitos.

His next question was “How many mosquitos do you think are on this campus tonight?”

“Hmm. Maybe a million or more.”

“Do you think that the total which you’ve killed matters in a total population of more than a million mosquitos? Pay attention to my lesson and try to ignore the mosquitos.”

None of us could rebut that mathematical argument, although it did nothing to relieve our discomfort at the pesky brutes. For me, those that I had killed did make a difference to my ability to attend to the lesson. Enough of a difference that I managed to pass this time around.

Dr. Chunilall’s coincidental “math-squitos” challenge—a valuable life lesson.

Back to the Table of Contents

NURSIE

1936 Birmingham Alabama

By Alice Giles

Soon after I was born my father decided that Mother should have help with the household tasks and the new baby. Because of his work, my father was very familiar with the colored town and knew many of the families. (I am using the word, colored, to refer to black people or those of African American descent. “Colored” was decent, polite usage at that time.) While driving through the colored community Daddy saw a woman who looked healthy and strong and asked her if she would be interested in working for him and my mother. There was one problem; her name was Alice as was mine. Daddy said she would have to use another name, and she suggested Nursie. Nursie did not live with us nor did she do any cooking. She helped with the house cleaning, washing, which was done in tubs with a hand ringer, ironing, and watching me.

For some reason I didn’t misbehave with Nursie. An early memory is of a hole on the back screened porch through which I enjoyed making small objects disappear. This was not a problem until I discovered that toothbrushes not only fit the hole but their disappearance caused consternation on the part of my parents. When Nursie was around, I didn’t bother with the toothbrushes.

One Easter, probably at age three, I received a fuzzy baby duck which had been dyed green. Duckie followed me everywhere, leaving his calling cards behind. When Duckie got too large to be a house pet, Daddy took him to Nursie’s house to live in the yard pen with other ducks and chickens. Much later, when Duckie was full grown and totally white, I went with Daddy to take Nursie home. I can remember looking through the wire fence and seeing a particular duck among several and insisting it was Duckie. Sure enough, Nursie later told my parents, I had pointed out Duckie, and Duckie would never be killed for dinner. No one ever confirmed that the large, white duck was Duckie, nor do I recall inquiring further.

One of my favorite story books was Little Black Sambo. Black Sambo chased the tigers around a tree so fast that they turned into butter. When Nursie read to me she would never say the word, black. I would say, “His name is Black Sambo.” Mother told me that Nursie did not say Black Sambo and not to ask her to say it. I obeyed, but no explanation was given. This may have been the first time that I had any awareness of Nursie’s black skin or that she was somehow different from other adults in the family who read to me.

By the time I began first grade, we had moved from the city to the county, in an area named Mountain Brook. The new house had a large drive-in basement where Daddy enclosed a room and adjacent bath with beaver board, and Mother put up pretty chintz curtains and added an old dresser, wicker rocker, and rug. The coal burning furnace kept the basement warm in winter, and it was always cooler there in summer. This area was called Nursie’s room. As I became older, I realized that Nursie changed her clothes after she arrived. I had no idea of the long bus ride with transfers she made across the city and over Red Mountain to the new house. Upon arrival Nursie would put on a freshly washed and starched colored dress with large pearl buttons down the front, a white collar, short sleeves, with a white bib apron on top. She would change back into her street clothes for the ride home. By this age, I was well aware that Nursie was not “one of us.” Other neighborhood families had black maids who cleaned, cooked, looked after the children and perhaps even lived with the family in a similar basement room. All my playmates knew, as I did, that we were not to interfere with any of the maids when they were doing their work.

It never occurred to me to wonder if Nursie had a family, and if so, who looked after them, who did her housework and cooking? Such matters were never discussed in my home. Why? To this day I can only guess or wonder why. Even though my parents were products of their times and culture, I believe if Nursie or any of her family were in trouble, my parents would have assisted her.

My weekly job was to polish silver. Mother, having taught me how to polish, put the silver to be polished on the breakfast room table for me to start on when I got home from school. I enjoyed the polishing and got satisfaction from the satiny gleam as the tarnish was removed. Because Birmingham was a major steel-producing city, the air, even over the mountain and in the county, contained a high percentage of sulfur. It was these sulfur gases that caused silver to tarnish easily. If Mother were not home, and Nursie had finished her work for the day, she would help me polish. If Mother was preparing to entertain, she might have Nursie polish during her workday. Nursie told me to never, never let Mrs. Cowles know that she had helped me polish. I never did. I wouldn’t dare. Mother died never knowing that Nursie helped me. How did Nursie know that she could trust me not to tell? This will always amaze and puzzle me. Since I was paid 25 cents a week for the polishing job, perhaps Nursie felt she was interfering with my mother’s raising of me.

Nursie would never eat with me. She always waited until all the family had eaten lunch and then eat alone in the breakfast room. I remember well how this bothered me. I wanted to eat with Nursie, and it was disturbing to see her eat alone for no reason that I could ascertain. When I asked my parents for an explanation, I was told that was the way Nursie wanted to eat, and she was more comfortable eating alone. This is just one of the many myths that have been told to justify our racist attitudes and relationships with the “colored” people. I think I was in my early 20s before I came to realize the irony of such a myth.

Back to the Table of Contents

The Richard M. Nixon Quick Weight Loss Diet

By Jim Herrell

[Written in recognition, but not commemoration, of the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, June 17, 1972.]

From my earliest days, I was a finicky eater. “Boy,” my exasperated father often warned me, “someday when you’re in the military, they’ll put food in front of you and make you eat it.” In November 1968, when I was an army psychologist preparing to enter my first military mess hall on my first day in Vietnam, his words were prominently on my mind. Surrounded by higher-ranking officers, I was more afraid of being ordered to eat asparagus by some power-crazed lieutenant colonel than I was of being killed by a Cong rocket.

I needn’t have worried.

Inside I found a hundred linear feet of my kind of food: Steaks, hamburger patties, fried chicken, pork chops, mashed potatoes and gravy, fried potatoes and ketchup, rolls, pies, cakes, ice cream, puddings. And that evening, I was introduced to our officers’ club where I could get bottomless whiskey sours. Until that day, I’d always been skinny, like Barney Fife in The Andy Griffith Show. A year later, I looked more like Ralph Kramden in The Honeymooners, and returned home 30 pounds heavier than when I arrived.

Back in the states, I continued gaining. I ate whatever and whenever I wanted, my exercise was limited to a weekly tennis match, and I avoided scales. I “dieted” occasionally, passing up chocolate syrup on my nightly dish of ice cream, for instance. At times, when my resolve to lose weight became intense, I’d buy the latest fad diet and exercise books, plunging into their prescriptions with vigor and commitment, once staying on a weight loss regimen three whole days. By the spring of 1974, I had blimped up to … well, never mind. Whatever I weighed, it was much too much. I had to find a weight-loss regimen and stick to it.

Thanks to the 37th president of the United States, I did.

For Nixon haters, a group of which I was a proud and unrepentant member, 1974 was a very good year, particularly when one could arise daily to find The Washington Post on the doorstep. Following the 1972 Watergate break-in, I got up each morning with a sense of excitement. What new revelation, what new misdeed, what newly uncovered, quintessentially Nixonian villainy would be reported above the fold? Surely his resignation or impeachment was imminent. Ah, and there was one particularly delicious night in June of that magical year when the 11:00 news showed footage of Nixon arriving in Cairo, his first stop on a tour of the Middle East. Three-fourths asleep, I faintly heard the announcer describing Nixon’s descent down the stairway from Air Force One, the cheering crowd, music from the Egyptian army band in the background. Wait! What? I sat up in bed, fully awake, laughing. The band was playing “The Washington Post March.” There he was, halfway around the world, hoping to divert attention from what Americans were reading about every day in that newspaper, and there was the band, welcoming him with that march. It was as if some cosmic comic had set the whole of time in motion just for that moment.

Yup, it was a great year for Nixon haters.

But not everyone hated Nixon, so that one spring morning the Post contained an ad from the “Committee to Support the President,” proclaiming “We love you, Mr. President,” entreating supporters to send contributions to continue the battle against Nixon’s enemies. The ad included a picture of RMN, a picture looking more like a Herblock cartoon than a photo, a picture emphasizing the famous close-set eyes, the infamous five o’clock shadow.

That morning, I began the Richard M. Nixon Quick Weight Loss Diet. I resolved to lose 30 pounds at the rate of two pounds a week, and to send a check to the Committee every week I didn’t meet my goal. I made copies of the ad and its photo, posting them in my office, bedroom, bathroom, and on the refrigerator door, and I carried the original in my wallet.

I followed no system other than “eat less, exercise more.” Sometimes at night, doing the Post crossword while watching the 11:00 news, I’d want a bowl of ice cream, but when I found affixed to the refrigerator door the testimonial to RMN, the urge would evaporate. When coworkers invited me to go to lunch at a favorite pig-out place, I’d decline, or I’d go but eat a salad while my colleagues ate triple-decker hamburgers and garlic bread and hot fudge sundaes. If I felt myself weakening, I had only to look at the ad in my wallet. Some evenings when I just didn’t feel like doing those pushups, I’d say to myself, “I am not a crook,” and exercise would become effortless.

Then one week not even Nixon could save me. I failed my Monday weigh-in. Hands trembling, near hyperventilation, I wrote a check to the Committee, photocopied it, mailed it, and posted copies everywhere I had posted the ad.

There was no further slippage. By mid-summer, I’d lost the targeted weight, but with that man still in the White House, I couldn’t abandon my vigil. I continued my program until August 8–9, when Nixon resigned the presidency, canonized his mother, and caught the last plane to the coast—but not before I’d lost an additional 10 pounds.

After meeting my original weight goal, I wrote an article about my regimen, which Harper’s tentatively accepted for publication. Alas, my visions of a Pulitzer were shattered when, after the resignation, Harper’s notified me that with Nixon gone and our long national nightmare over, my article was no longer of interest. I had to cede that point to Nixon, but still, 48 years later I have (mostly) kept the weight off.

Back to the Table of Contents