Travel with Osher!

Spring/Summer 2022

Volume 32, Edition 1

Contents

Funnel Vision

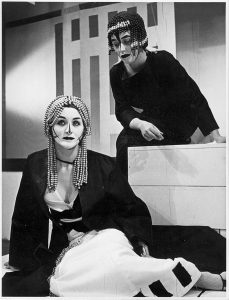

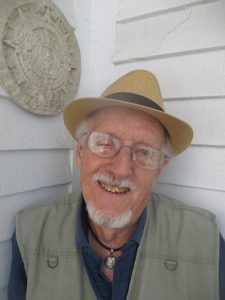

By Roger Brunyate

Looking back, I see my professional life as a main course framed by appetizer and dessert. The main course has been my 45-year career of putting operas on the stage. The appetizer was the exciting period of imaginative expansion in my college years and just after, when it seemed I could try my hand at anything. The dessert has been teaching at Osher, where I can also tackle just about anything. I see it as a funnel into which I can pour ideas from everywhere and have them emerge —on good days—as a single coherent stream.

The funnel analogy works particularly well for opera. Germans call opera a Gesamtkunstwerk, or combination of all the arts: music, poetry, drama, and design. And the person most responsible for throwing everything into the funnel is the stage director—my former job. It called upon the smorgasbord of skills and knowledge I had picked up in my appetizer years; it let me combine all my hobbies and make them into a profession. Yet it had a downside.

This intense focus could result in a narrowing of perspective, rather than the expanded horizons that had got me there in the first place; that funnel could too easily become a tunnel. But my Osher teaching has released me from that; I no longer miss the spotlight, because now I am in the light of day.

Although a generalist at heart, I am the product of the curious private educational system in Britain of the time that imposed specialties almost from the start. At the age of 10, I was sent to a boarding school that taught almost nothing but Latin and Greek. Reacting against that, I became a science major in school. Reacting again, I switched to English at Cambridge. Meanwhile, I had taken up painting, which in turn led me to choose Art History for my Master’s. And when I was offered a job as a research assistant cataloging the important collection of Whistler papers at the University of Glasgow, it seemed the perfect combination of my two degrees: words and art. So at 22, I set off for Scotland.

I loved Glasgow but hated the job. However, I did not have to keep it; just before the fall term began, a junior lecturer in the department resigned, and I was hastily promoted. This involved teaching chunks of the Art History survey course, most of which were entirely new to me. I worked frantically, studying artists such as Giotto, Masaccio, and Donatello, whom I would have to teach the next week or sometimes even the next day. It was a period of intense learning. Those five years in Glasgow were a period of expansion in other ways too. I made extra money by teaching extramural courses in communities very much like those in Osher. I spent it on my first real piano teacher, who encouraged me to learn some serious repertoire. I was also making music with other people: several singers, a violinist, piano-duet partners. I got occasional work with both The Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman, writing reviews of theater, musicals, and ballet. And most significantly of all, I was invited to design a production of Love’s Labour’s Lost which the English Department put on for the Shakespeare quatercentenary in 1964.

It was not a very good design, but the theater bug had a bit. The next year, I mounted a production of my own, then two more after that. I designed for other directors. I learned stage lighting. I stage-managed and even acted. And all the time, I was making music, which was always my first love. I had often thought about going into music in the past but knew I was never good enough as a pianist. Now it struck me that my new theatrical skills, combined with my academic studies, might together comprise the “instrument” with which I might enter music professionally as an opera director. I went to see the manager of Scottish Opera, who offered me a summer internship at the Edinburgh Festival. With no other security but that, I resigned from my lectureship and moved to London. It was hard at first to get work, but that wild leap into the dark has always felt right.

Quite early on, I saw the need to combine my professional work with teaching, which would provide some kind of intellectual continuity, so I came over to this country. I suspect that my work as a teacher will turn out to have been a greater contribution than the sum of my productions. And it seems that the same skills required to bring in production on time and on budget apply equally well to running a Conservatory department.

Each production, though, remains a matter of throwing stuff into that funnel and distilling the result. But if so much goes in, you need some way to sort and filter it; you need a focus: fidelity to the text. I don’t mean literal fidelity; I am quite prepared to update the period or modify stage directions if I feel it brings a modern audience into closer touch with the composer’s central point. And that central point emerges only from study of the music. You have to blind yourself to influences that are not tied in some way to the score. I have seen a lot of opera, but I learned early on never to see a production of something that I knew I was going to do myself. I watched no DVDs. I seldom even listened to recordings, preferring to study the music solely at the piano, to work out my own ideas without intermediaries.

I have to say, though, that such fundamentalism could make me arrogant and intolerant. While I have been generous with younger directors whom I mentored, and have recognized a few masters so far above me that I could learn from them without problem, I have always been critical of other directors at my own level. Outwardly, I would try to be supportive with colleagues or directors that I hired, but inwardly I could be consumed by corrosive jealousy. I have never liked this about myself. No matter how much I attribute my criticism to loftier principles, in truth it is a character flaw, exasperated by my particular choice of profession. Funnel vision had become tunnel vision, and the tunnel was a trap.

Retirement 10 years ago removed the problem, and teaching at Osher has returned me to some of the exhilaration of my Glasgow days, when anything seemed possible. In teaching about opera, for example, I have had to buy DVDs; I now have 400 separate productions on video, almost all new to me. Some are wonderful, some are off-the-wall, a few are just plain bad, but what excites me is the range out there; I no longer have to feel threatened by any of them.

The tunnel has once more become a funnel. I no longer need to be a specialist. Half my courses now seek ways to combine all my old interests and new discoveries, whether in the visual arts, music, poetry, or dance. The task of bringing these things together into a series of entertaining classes has become an act of creation in itself, involving my technical interests quite as much as my artistic ones. And sharing this material with people who regard it as a gift has been a gift to me as well.

Back to the Table of Contents

A Three Watery Crisis Triptych

By Randy Barker

1963

“God…this may be it…can’t get out of this current…” “Me too…oh no…”

Our Lambrettas were parked on the gravel bank, clothes tossed over them. It was summer 1963. After a grueling first year, I and my brother chose to get as far as possible from med school. That meant buying Lambrettas (Italian motor scooters like Vespas) in Paris, taking a train to Irun de la Frontera, traversing Spain on unpaved dusty roads, getting to Andalucía, getting to Cordoba. We had swum from the bank of el Rio Guadalquivir to the ruin on an island in the river. We had jumped back into the Guadalquivir to swim to the other side. We had chosen the side where the current was strong and fast and capable of carrying us along like two bits of driftwood. We realized this too late when there was no way to swim out of this nightmare. We said goodbyes. “Remember lifesaving at camp…?” “…that film of a guy being dragged by a river current…” “…just let the current take you…eventually it will drop you…safely…” We grabbed onto that life-saving lesson…and we found ourselves ashore far down-river. We lay there. We got up. We made it to the bridge, then to our scooters. We would return to med school after all.

1981

“She passed the swimming test at the pool last month…I think she can…” Yes, look how well she is swimming…” We watched from the bank of the Lot, about 75 to 100 feet across. Our 12-year-old daughter was swimming across to the other side. This is the kind of adventure we enjoyed around this river we knew well, in southwest France. None of us had swum across it before. But it is a lazy river. Looked like an easy swim. “She’s not getting to the other bank…she just seems to be heading down the side of it…can’t get to it even though she’s swimming pretty hard…” “She’s in trouble!” As best as I recall I swam across. Found that the sluggish Lot has fast current by that bank, so fast you can’t swim across to the bank. We both turned round and slowly swam back to the place we started from. Turns out every river has fast current running next to one bank. It can be hard to see it. Never again.

2012

“I bumped into something huge…” (she coughed and could say no more)… “You OK?” “Oh no…here I am. Let me pull you…” I got her on my hip side and slowly fin-swam us back 50 feet to shore…touching bottom about 20 feet out.

“We’ll take snorkels, goggles, fins…don’t need the vests…” was how I voiced misplaced bravado at the rental booth. We had made several snorkeling trips to Akumal on the Yucatan. Save a buck by skipping the life vests was typical of me. New this year were restored huge sea turtles. They said we might see one. Marie Claire collided with one. That gave her a scare. Sucking water in, not blowing it out the snorkel tube came next. Then panic. More sucking in. I had the stamina to swim us both back to safety, from what would be our last snorkeling swim. I said to myself, “Never forego life vest rental.”

My three watery crises spanned 50 years. I can revisit them in an instant. Each brought closeness to a bad ending. Each a denouement that let me continue life’s adventure.

Back to the Table of Contents

Holding Hands

By Judy Ashley

Before dark, in the last 20 minutes of light, my parents often went for a walk. Our neighborhood included many old homes, huge maple trees, and a whir of car engines a block away on the main highway cruising through oldest section of the business district. If you walked north, a large three-storied building around the corner housed a ballet school, and we called it the “conservatory” and envisioned professional students there. In a very few minutes, a walk around the block conjured many tales of exotic experiences, if one made the effort to imagine.

No memory of ever walking with them, I recall watching from our front porch swing, enjoying the complete sense of love. They always held hands. My father politely walked nearer the curb, and my mother in her fashionable high heels walked on the inside of the sidewalk. They always talked, I noticed, but my curiosity seldom seemed concerned about the topic.

Within a short while, enough time to walk around the block, they returned and I packaged the sight of their clasped hands as my goal someday. Unexpectedly, not long before my first serious boyfriend, while visiting my mother’s parents, I learned about another type of love. My grandfather, the carpenter, the builder, the doer, took me with him to many shops with tools, paint, old furniture. He allowed me to collect nails, screws, pieces of wire; he read westerns about cowboys, gulped orange soda often, and devoured entire bags of orange marshmallow peanut-shaped candy; he never whispered, hugged me, or seemed tender.

My grandmother, a petite woman, soft-spoken with cute puffy cheeks, played cards with me using a whispering voice, taught me to sew, and helped me paint colorful ceramic statues. She suffered a stroke, but survived and required a lot of physical therapy. Grandpa immediately rigged a contraption in the doorway to the parlor with pulleys. He collected bottles of oils, creams, and round objects to squeeze with your hands. Twice a day he placed Grandma in a chair with a pillow, and he sat across from her at the table. She stretched her arms on the pulley, he supervised her moving round objects to improve her grip, and he removed warmed oils from a pan with hot water to massage her fingers. Faithfully twice each day he sat with her as the physical therapist. He clasped her hands with gentleness and slowly moved his thick fingers back and forth, back and forth. The sight of his hands covering her fingers remains my perfect sense of love.

Back to the Table of Contents

A Capitol Playground

By Betty Spear

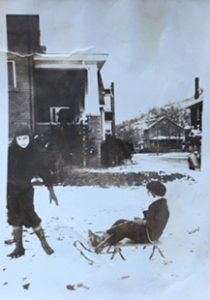

Looking back, I realize my brother Lee and our friends were privileged to have a playhouse with marble walls, a real golden roof, and a labyrinthian skating area, a virtual fairy tale castle. This is how we regarded the West Virginia state capitol. We lived in the capitol’s shadow, about a block away and near the scenic Kanawha River in Charleston.

Begun in 1921 and completed in 1932, it is a handsome building with a gold-plated dome. This massive elegant building resembles our national capitol and belies the common thought of West Virginia as a rural state populated by hillbillies and miners. Note to its completion date, 1932, was in the midst of the Great Depression.

We lived near the South entrance to the building and our Grandparents lived at the North end. You could walk through one wing, across the rotunda, through the West Wing, and out the other end to their house. Our house one block away made it easily accessible for us and the neighborhood kids to go there. It provided a variety of activities on a rainy or snowy day when we couldn’t play outside.

The capitol basement had a maze of hallways paved with very smooth concrete which made it perfect for roller skating. A long driveway leading to the basement entrance and loading dock provided us with a speedy if a bit scary, place for bicycling or sledding; you had to watch for cars and trucks as the momentum you gained on the slope made it difficult to decelerate at the bottom.

The Post Office branch was convenient for mailing letters and packages. As budding philatelists, my brother and I bugged the postal clerks, to their chagrin, about new stamps. We found a rich source of used stamps in the large wooden trash bins located throughout the basement. Being more venturesome and the smallest, I was the one boosted over the top into the bins to look for discarded envelopes. This became a rich source of stamps from around the world and my young innocence kept me from being bothered by the stale sandwiches or cigar stumps in the bins. Duplicates of stamps we already owned came in handy for trading with other collectors.

Sometimes just for the heck of it, we visited the museum located in a corner of the basement. We didn’t stay long, since the curator objected to our signing the guest book as Mickey Mouse and Shirley Temple, and told us not to come again, but we did anyway. It displayed Indian relics, costumes, and artifacts concerning West Virginia and its history. I especially liked the flea circus featuring costumed fleas that you viewed through a microscope.

We sometimes parked our bikes to board the elevator, ignoring the sign clearly stating For Legislators Only. The more daring boys stopped the elevator between floors to aggravate the lawmakers. When the delegates’ and senators’ patience nearly reached the limit, we descended to the basement, skipped off the elevator, and scurried up the ramp, the picture of innocence on our young faces.

Great excitement accompanied the lowering of the giant chandelier that hung under the dome at the top of the rotunda. It needed cleaning. What looked like a sparkling basketball from far below became a massive sphere covered with prisms reflecting and refracting light in all directions. I felt like a dwarf standing next to it because it seemed to fill the whole rotunda.

This big event drew many visitors. Stairs led to the top of the rotunda, but I don’t remember ever going there. We wandered the elegant marble hallways and occasionally visited the legislative chambers, the Supreme Court, and the Governor’s Office. We played with the governor’s children at the governor’s mansion.

Every Easter a sunrise service took place on the capital grounds overlooking the river. Worshippers awakened us as they passed our house before dawn to celebrate the holiday. The crowd numbered in the thousands.

Senators, delegates, and other workers patronized the drug store across the street from the state house. If you collected one dollar’s worth of receipts from the store’s sales, you could get a credit for five cents which amounted to the cost of an ice cream cone. Especially on hot days, we hung out near the door watching for customers discarding their receipts as they exited the store. We collected the castoffs until we had enough for a cool treat.

I feel quite certain that kids today do not enjoy the capitol as we did. In fact, I can imagine guards are stationed at every entrance and the doors to the basement are kept locked. Life and society have changed tremendously from the world we knew in the mid-1930s.

Back to the Table of Contents

Touché

By Les Weinstein

I do not like poetry; never have and never will! I find most of it inaccessible, too esoteric, and difficult to interpret.

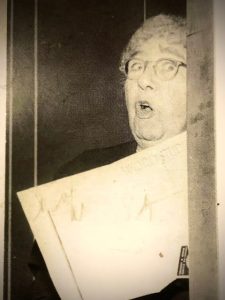

In 1956, as a senior at Hope High School in Providence, Rhode Island, the English course I was required to take that year was Poetry. I dreaded taking this course, even though Miss Isabelle Hall, who taught it, was known to be a really smart, fair, and outstanding teacher with a great sense of humor. She was also the head of the English Department and was admired by students and faculty alike.

At the beginning of the semester, Miss Hall told us our first assignment would be to select a poet to write a research paper on, including detailed information on, and analyses of, that poet’s poems. I panicked! How would I ever find a poet whose work I could delve into and figure out what was being said, why it was being said, and what it all meant?

I did a lot of research on various poets and finally found one I could use for my paper: the American poet Ogden Nash. He was very well known for his humorous and whimsical light verse, as well as for unusual and clever rhyming schemes. Some of his poems even made me laugh out loud!

I still remember one that did: Reflections on Icebreaking, which goes like this: “Candy is dandy, but liquor is quicker.” That’s it! That’s the whole poem! Writing the paper turned out to be a breeze. It was all so easy to do the research, understand the poems, and write about them, that I still feel guilty about choosing such an unchallenging poet as Nash and his work. Well, just a little bit!

During a class later in the semester, Miss Hall asked us to come up with a current popular song, so she could show us why its lyrics were probably not very good poetry. I suggested “Unchained Melody,” which I thought had great lyrics. Written and sung by Al Hibbler, it was a big hit that had reached #3 on the pop charts, sold over a million records, and won a Gold Record Award. It was also great for slow dancing! Miss Hall asked me to say the lyrics out loud, because she had never heard of this record or Al Hibbler! The following are the lyrics:

“Oh, my love, my darling

I’ve hungered for your touch

A long, lonely time.

Time goes by so slowly

And time can do so much.

Are you still mine?

I need your love,

I need your love.

Please speed your love to me.”

“Lonely rivers flow

To the sea, to the sea

To the open arms of the sea.

Lonely rivers sigh

Wait for me, wait for me.

I’ll be coming home, wait for me.”

As I was saying these lyrics, Miss Hall kept interrupting me, criticizing practically every word of the song, its sentiment, meter, rhyming scheme or lack thereof, and generally making fun of it. I found this so annoying, as she seemed to know so very little about my generation’s music and showed no appreciation for it at all. I began to think how I could rebut her effectively. I remembered a poem by Robert Burns we had read several weeks before, and I quickly found it in my textbook. It is called To a Louse: On Seeing One On a Lady’s Bonnet, in Church.

Burns wrote poems full of antiquated Scot’s language, as well as nonsense words, phrases and syllables he made up, which one critic called “smirk-inducing.”

I raised my hand and said to Miss Hall something like: If she did not like the beautiful Unchained Melody, I wonder what she thought of the very different lyricism of Scotland’s greatest poet! I also asked her to explain why the lyricism in To a Louse… was better than that in “Unchained Melody”. Then I started to read the Burns poem aloud as follows:

“Ha! Whaur ye gaun, ye

crowlan ferlie?

Your impudence protects

you sairly:

I canna say but ye strunt rarely,

Owre gauze and lace;

Tho’ faith, I fear ye dine

but sparely

On sic a place.”

There are several more verses to the poem, but this was as far as I got because the class was laughing and applauding so much! Miss Hall, laughing also, graciously said “Touché!” Her use of this fencing term indicated that she knew I had one-upped her in our verbal parrying.

The summer after graduating from high school, my friends and I would go to a dance at a community center every Wednesday evening. One time, the Everly Brothers, who were to sing at a show in Providence that weekend, made a surprise visit to the dance to sing a few of their songs. At that time, they were one of the most successful acts in popular music. I was in the lobby when they walked in. They asked a woman, who had volunteered to help that evening, in what room the dance was being held. She told them the room number, and then said: “That will be 75 cents for each of you.” One of them replied: “But we’re the Everly Brothers!” She said: “I don’t care who you are; everyone has to pay 75 cents!”

I remember thinking that here was another adult, who like Miss Hall, was clueless about the popular songs, and the people who sang them, that we teenagers loved! If Miss Hall had been there that evening, I could only imagine what she would have said about the lyrics of the Everly Brothers’ songs, especially “Wake Up, Little Susie”!

Two years later, Brown University, also in Providence, awarded Miss Hall an Honorary Doctor of Letters (LittD) degree. I was then an undergraduate at Brown and attended the award ceremony. She had graduated from Brown in 1908 (from Pembroke College, which at that time was the university’s women’s college). Of the 15 people on the Honorary Degree list, only two were women, Miss Hall, and the actress Helen Hayes.

The citation supporting Miss Hall’s honorary doctorate, read aloud in English (“I grant to you …”) and Latin (“Tibi concedo …”) by Brown President Barnaby Keeney, stated: “We honor you as a teacher who has brought to her classroom both scholarship and perception. While educators argued whether students of different ability should be taught differently, you quietly did it, thereby restoring true democracy of opportunity to one school. While others who taught the child forgot the subject, you proved once again that affection and understanding are a basis of, not an impediment to, exacting standards.”

I felt so proud of her, and so very lucky to have had such a wonderful and distinguished English teacher in high school, that I said to myself in a whisper, “Touché, Miss Hall, touché!”

Back to the Table of Contents

Turning Back the Grandfather’s Clock—A Diptych Uncle Sam—“De Old Boy”

By Sam Dowding

Even as I smirked sanctimoniously at his “green” verbs, I secretly admired his courage and competence in delivering Good Friday “last words of Christ” sermons. My father had only six years of primary education, but was for many years a church warden and local government councilor, in addition to his job as an assistant engineer in the sugar factory.

He was 45 when I was born, and I do not recall him ever playing with me, teaching me to ride a bike, or play cricket. But as a descendant of slaves in this yet colonial society, he stressed the importance of education as the means to rise above our societal station. My dad would never sit idly by should any of his children, but particularly his only son, fail to grasp and climb the rungs of the education ladder. As he encouraged us, he was equally unabashed to threaten or apply physical punishments whenever our efforts seemed to flag. Honoring the sacrifices of our ancestors was imperative.

Until I was 17, our relationship reflected a strained wariness. With youthful lack of enthusiasm, I chafed as he demonstrated the value of service. He took me along to his local government conferences and to his lay ministry visits to the shut-in. I saw, and often resented, his active roles in church management, serving in positions that belied his limited education.

My less-than-stellar high school career was disappointing to us both. His threat that I must return to high school for another year incentivized me to promptly pursue a university education. I surprised myself, and pleased him immensely, by doing better there than I had in high school. He was so proud, he positively beamed! Although I was not a top student, it was the leap from primary education to a university graduate in one generation that made his heart swell.

Four years prior, I had landed my first real job as a trainee auditor in the Guyana Civil Service. That evening, upon reporting my success, he sat me down on the veranda of our home. He did all the talking, the gist of which was “Son, be diligent, listen to those above you. With dedication and belief in yourself, you could go quite far!” I listened impatiently, but what struck me and still impresses me was the qualitative change in our relationship that slowly unfolded. You see, my dad had retired earlier that year after about 50 very hard-working years. With me now being the employed male in our home, it felt like he was passing the baton. Years later I came to recognize that thereafter we had become friends.

Friends…but not peers. Among other lessons, he had taught me to mix and lay concrete, to paint our home, to drive, to care for the welfare of others, and to serve the church. His singular failing is that I still do not have a green thumb! Thirty years since his transition to the afterlife, I dream of him beaming at those successes which I owe to his stern upbringing, though then resented.

CB

Although he had never left Guyana, the land of his birth, my wife’s dad, CB, was a “dyed in the wool” Barbadian. He was a character, infuriating, loyal, and traditional. He supported Guyana at cricket except when we played Barbados. His parents were born in Barbados but had met and married in British Guiana in the early 1900s, probably seeking a better life in the much larger fellow British colony where land and natural resources were more plentiful than in tiny Barbados.

CB forbade his daughter from dating me, demanding that I should come to ask him personally, which I never did, thereby prompting an eight-month hiatus in our early relationship. He was so traditional that he required his sons-in-law to “write home” to seek his approval to propose. The two before me, that is—I rebelled.

CB so loved the board game “draughts” (“checkers” in the USA) that he and one particular buddy would play continuously from Saturday noon till midnight every weekend. Only the looming early church service on Sunday would force them reluctantly to halt the scratchy sounds of the red and black plastic checkers as they were nudged across the board. These gentlemen played studiously, nodding knowingly at each other when either had set a trap, interrupted occasionally with quiet commands to “Huff me” or “King me!”

He ardently loved his weekly coo-coo (a Barbadian dish of cornmeal and okra) such that his native Guyanese wife and four daughters all had to become expert at its preparation. CB’s propensity to argue for the sake of the argument was renowned: the point was not the point. I recall with wry amusement the time that he and I had argued for 10 minutes about “maintenance” versus “maintainance,” when he switched sides so deftly that I was slow to realize that he was now accusing me of advocating the incorrect spelling.

He ended arguments, whether won or lost, with the interjection “Done wid you!” But my fondest memory of him was of the day that I returned to Guyana from my first two years living in Belize. CB and I started arguing “ding-dong” within minutes, about something truly inconsequential. In frustration, I exclaimed, “CB, ah just come back and we already arguing—leh we done dis, man!” His face erupted in a big smile, followed by “Ow, boy—ah miss you!”

Back to the Table of Contents

Jon Minton

By Phyllis Geiger

We all have favorite memories of our children when they were young. This is one of mine when my son was about four.

They passed by each other on the stairs. “Who are you talking to?” Allison questioned her brother. He was talking with someone, but she couldn’t see anybody else on the stairs.

“Jon Minton,” Craig answered with a matter-of-fact tone in his voice.

Allison looked at him quizzically. At six, she had a very concrete and literal view of her world. She gave him another glance as she continued down the stairs shrugging her shoulders and muttering, “Weird brother.”

Craig had his imaginary friend for the better part of his fourth year. When I asked him who Jon Minton was, he replied, “Oh, he’s the bad guy.” I finally understood. Craig always wanted to be seen as the good kid and tried to please those around him, especially adults.

As he grew older, I teased him a bit about Jon Minton. He took it all with good grace and humor. In high school he used to give me two cards since my birthday fell very close to Mother’s Day. One he would give rather reluctantly because he knew I wanted a serious, sentimental card, but he didn’t think it was really “cool” for a high schooler to give his mom a card like that. So, he solved his dilemma by getting a sentimental card for Mother’s Day and a comical one for my birthday, addressing a timely topic, which he gave with enthusiasm. The most memorable was a picture of footprints tracking in mud onto a cleanly mopped floor. Signed, Jon Minton. To this day, Allison doesn’t understand the humor in all of this. She still thinks of Jon Minton with some bewilderment.

Back to the Table of Contents

The People You Meet On Zoom

By Elizabeth Levy Malis

“Randy Barker”, the name peeped out of the Zoom screen. It rang a bell.

I racked the far reaches of my brain to realize that I heard the name Randy Barker from my father, Dr. Robert I. Levy, a nonagenarian retired physician, who lives at Roland Park Place Retirement Community. He never referred to this Randy Barker, his friend and fellow member of Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at Johns Hopkins University, as “Randy” or “Dr. Barker”— it was always Randy Barker—two words, together, first and last name pinned at the hip. This name came up in the context of transportation.

First, a little background: my father has attended classes through Osher for eons. Originally, he went with my mother when she was alive. They attended the Institute as a couple. They smiled about the classes—Shakespeare, classical music, opera, and politics were among their favorites. When she passed away after 50 years of marriage, he diligently continued to go alone. I believe it helped him mourn and adjust after her death. Proudly, he always drove himself to class, even as he reached his 90th birthday.

However, as he turned 91, I took his car away from him. I don’t think anyone should be driving in their 90s, although he kept telling me “There’s no law that says you have to give up your car at a certain age.” Once his car was gone, he got entrepreneurial about getting to Osher. He asked me if I could help drive him, which I did when possible. But with a job and two special needs children adopted from Eastern Europe, I wasn’t always available.

Enter: Randy Barker. He kindly offered to include my father in a small carpool down Roland Avenue, over to Charles Street, and to Grace United Methodist Church, the site of the Baltimore classes. My father delighted in this regular opportunity to get driven to Osher as well as—it seemed to me—in how he orchestrated this arrangement all on his own with no help from me. Or before me, it would have been my mother, who managed all logistics of their life together, leaving him free for intellectual and medical foci. So, that’s how I associated Randy Barker in the matter of transportation.

Fast forward a few years to the next time I heard—or, more accurately, saw—the name Randy Barker. When visiting my father’s apartment, I looked at his wall next to the front door. He was now about 93 years old. He had something new there.

Prominently placed and nicely framed, a photograph hung atop a typed poem with a signature scrolled on a slight diagonal across the bottom right. The photo documented my father playing his grand piano in his apartment beside familiar walls bejeweled with his mother’s oil paintings. It’s the same piano he has played since he was a child, although it has been rehabbed a couple of times. In the foreground of the photo, some visitors as audience sit in the turn of the 20th century, yellow-striped chairs that belonged to my grandmother—they had been rehabbed a few times as well. This poem spoke about music. It captured a bit of my father’s life story, and it praised my grandmother’s artwork, too. Plus, it seemed to be a creative thank-you written and signed by none other than Randy Barker.

Mind you, I never met Randy Barker until Fall 2021 when I took an Osher class taught by Diane Scharper. She is someone who had always been on my radar—ever since I read an article about her in The Baltimore Sun about the popular classes she taught on writing memoirs. I have always wanted to take her class but, alas, was always so busy in the middle of the day that I never had the chance until the Covid-19 pandemic slowed all life down.

That’s when that familiar name popped out at me from the Zoom screen with a face attached. Now, I learn that Randy Barker was not only a fellow member of my class, but he is a doctor—like my dad. I had no idea. No matter what my father likes to call him, he’s Dr. Barker to me. Also, I discover that he’s the teaching assistant for the class as well as an insightful and prolific writer who has been writing for years. Finally, I meet him “in person” through Zoom thanks to Osher.

On Zoom, I introduce myself to him. In front of the class, we exchange a few stories about my father who is now close to 95 years old. The friendship and kind words Dr. Barker shares about my father touches me deeply—for, in fact, in his retirement my father strived to remain fiercely independent to the point I didn’t know much about his daily world. Although Osher remains always at the ready for people to expand their minds and knowledge base, it’s also a great way to make connections. Even across generations.

Back to the Table of Contents

The Donut

By Jim Herrell

It’s embarrassing to admit now, but until I was in my 30s, I was a Yankees fan, which happened by chance. My hometown, Austin, Texas, was over 700 miles from the nearest major league team (Saint Louis Cardinals), so there was no local team to follow. When I was seven or eight, I came home from a friend’s house one summer afternoon to find my father working on his car and listening to a baseball game on the radio. “Who’s playing?” I asked, and my father said the Yankees and somebody. “Who’s winning?” I asked, and he said the somebodies.

My family always rooted for the underdog, so I decided I’d always root for the Yankees. Little did I know. From 1951, the year (plus or minus one) I became a fan, until 1963, when I first saw them in person, the Yankees won 10 American League championships and seven World Series. But I’m an Orioles fan now, condemned to rooting for the underdog in perpetuity, and the Yankees are hated rivals.

The 1951 Yankees roster included Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Phil Rizzuto, and Whitey Ford. Anytime preteen boys got together for a pickup baseball game, each of us wanted to take the name of his favorite player, and most of our favorite players were Yankees. In my neighborhood of origin, disputes were usually settled by physical altercations, so if more than one boy wanted to be, say, Yogi, there’d be a fight. No taking turns, no flipping coins, no drawing straws, no rock-paper-scissors, just a few busted lips, bloody noses, black eyes, or once, a broken arm, someone would get to be Yogi, and we’d do it all over again the next day.

In late August 1963, I was 20 years old, had just graduated from the University of Texas, and was a few days away from entering graduate school at the University of Maryland. Until leaving Austin for Maryland, I had been outside Texas only three times: To Colorado when I was four, a trip I remember only because I’ve been told about it; while in junior high to Las Cruces, NM, to visit an uncle who was stationed with the Army at White Sands; and with my parents to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, to buy handmade wooden furniture. “Worldly” is not an adjective anyone would have attached to me.

The weekend before classes started in College Park, I made my first trip to New York City, with five objectives: go to the top of the Empire State Building, ride the subway, see a Broadway show, walk in Central Park, and most importantly, attend a Yankees game, all of which I accomplished. I saw Beyond the Fringe, and I watched my (then) beloved Yankees play the Red Sox. Although the Yankees lost, and neither Mantle nor Maris played,

it was my first major league game, it was in Yankee Stadium, and

I WAS THERE.

I had one other first that weekend, although I didn’t realize it at the time. Not wanting to waste time sleeping, I set out early every day. Heading for the subway one morning, I saw through a shop window a tray of beautiful donuts.

I went inside.

“I’ll take one of those,” I said, pointing.

“You want cream cheese on it?” said the man behind the counter.

“No,” I said, uncertainly, not wanting to offend him. New Yorkers seemed to have strange eating habits, as I’d begun to suspect in a restaurant the night before when I’d asked for tea and had received a cup of hot water and a tea bag.

“Want it toasted?” said the man.

“No,” I said, more firmly.

“You want it sliced?” said the man.

“No,” I said, with perhaps a touch of irritation. “Just give me one.”

“You’re the customer,” said the man, or more phonetically, “Youse da custamuh.”

My purchase seemed as heavy as a dozen donuts; it was hard, chewy, and not at all sweet. “New Yorkers,” I snorted to myself, “don’t know squat about donuts.”

Back to the Table of Contents

What Should I Write?

By Ann Luard

My mom tells a story about me, and I half remember it. At least, I think I do. I was in elementary school, first or second grade, and our teacher took us outside for a walk around the school building. Perhaps it was a beautiful spring day, and maybe we were too antsy to focus, and she decided we could all use a dose of fresh air. Public School 203 occupies one whole block in the middle of residential Flatlands in Brooklyn, New York. Houses are side by side, punctuated by driveways. A significant number of broadleaf trees erupt at intervals from the cement sidewalks, sometimes lifting portions of sidewalk, exposing their thick old roots. Well, our homework that day was to write about our walk. According to my mom (and I can almost hear myself) I asked, “Mommy, what should I write?” She gently guided me asking, “What did you see? Did you see trees? What did you hear? Did you hear birds?” My mother’s story ends there, but I imagine that my reaction was in keeping with my practical and very literal nature. I probably wondered why anyone would be interested in that but dutifully wrote the prompts she gave me.

From all the stories in my little-girl world, why would this one loom so large? Probably for the same reason that, years ago, I was listening to an interview on NPR with an author (whose identity I will never remember) when the hair on my arms stood on end, a chill ran up my spine when he answered the interviewer’s question by saying, “You don’t choose writing. Writing chooses you.”

Back to the Table of Contents