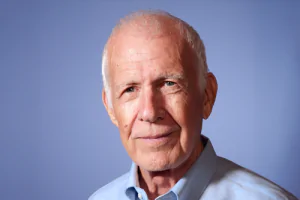

Robert Clark: Celebrating the Mind of a Master Intelligence Analyst

Published July 25, 2025

Like all the deep thinkers and Renaissance men who proceeded him, recently retired Johns Hopkins lecturer Robert Clark credits his interests across various disciplines with expanding his mind and keeping his synapses firing. At age 87, Clark has just now stepped away from a decade of impact as a lecturer in the MS in Intelligence Analysis program through his popular course “The Technical Collection of Intelligence,” that he literally wrote the book on. It is one of six books that he has authored or co-authored.

Like all the deep thinkers and Renaissance men who proceeded him, recently retired Johns Hopkins lecturer Robert Clark credits his interests across various disciplines with expanding his mind and keeping his synapses firing. At age 87, Clark has just now stepped away from a decade of impact as a lecturer in the MS in Intelligence Analysis program through his popular course “The Technical Collection of Intelligence,” that he literally wrote the book on. It is one of six books that he has authored or co-authored.

“Bob’s class was one of our most demanding courses, and for this reason, probably one of the most popular,” said Program Director Michael Ard. “It was a great privilege to have him teaching in our program. For many years, Bob has been one of the most important contributors to intelligence studies. Few people can boast of his intelligence credentials, having been a United States Air Force intelligence officer and a senior CIA analyst specializing in methodology, or his education, having earned a bachelor’s degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a PhD in electrical engineering from the University of Illinois, and a JD from George Washington University. His numerous high-quality books such as – Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach and Deception: Counterdeception and Counterintelligence – are widely used in intelligence studies programs. We will miss him.”

Clark, who capped off his academic career with recognition from the International Association for Intelligence Analysis as the 2025 Instructor of the Year, credits his personal curiosity for broadening his mind, sharpening his critical thinking skills, and catapulting his career and far-reaching influence. He also puts a finger to his temple and singles out his grey matter as the source of attraction for his wife of 22 years, Abby, who famously declared, after being asked what she sees in Clark, “It’s his brain. He thinks more than any man I know.” The father of four, grandfather of seven, and great-grandfather of two, has had two of his children follow him into service with the CIA.

“I am and have always been curious, and I read a wide range of material from a variety of disciplines – economics, history, fantasy, science fiction and even newspapers – to stretch my imagination,” said Clark, who calls Wilmington, NC, home. “I can tell that I am slowing down a bit, but I am still continually curious.”

Encouraged by a high school science teacher to take his curious mind to MIT, Lieutenant Colonel Clark flew B-52 bombers as part of the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command where he served for seven years of active duty and 13 years as a reservist while at the CIA.

“I have seen the North Pole and Greenland and the edge of the Soviet Union while flying airborne alert missions,” he said. “As a reservist, I was flying cargo planes to Europe and the Far East. And I once encountered rocket fire on takeoff from DaNang airfield just before the end of the Vietnam war.”

The legendary Dr. Julian Nall, himself an MIT graduate, a “soft-spoken Tennessean who guided me through all of my mistakes,” mentored Clark at the Agency and helped hone his technical analysis of radar, electronic warfare, and communications.

At the CIA, Clark was the first person to figure out that some powerful Soviet radars weren’t going to work, and their rusted remnants, he shares, remain scattered around Russia to this day. He also headed a project for the National Intelligence Council, the premiere Intelligence Community organization, to assess how much the Soviets knew about U.S. space systems.

After leaving the CIA, Clark continued to consult with the government as the cofounder and CEO of the Scientific and Technical Analysis Corporation. He brought five decades of work into the Hopkins classroom to develop the next generation of intelligence analysts, folks like him who rely on their personal curiosities, their abilities to apply logic and reasoning skills, and their work ethics to analyze, interpret, and problem solve.

“Critical thinking is the single most important quality that distinguishes success in the intelligence community,” Clark said. “Realizing that the world is beguiled with misinformation, distorted and misleading information, and propaganda, I have told my students you have to be able to look at what is happening, what you are reading, and the situations that are developing. Then you need to step back and think critically and analytically about what is going on and determine what is likely to happen next. Intelligence is a complex and technical field. I wanted my students to understand that there is more than just open source and human source that we can use to collect intelligence, and that it is worth knowing what the limitations of these sources are – how they can help you do your job, and how to be careful in using them. I always wanted to teach my students to take steps beyond what they knew into what they didn’t know and to leave saying they learned a lot about stuff that they never knew they needed to learn about.”

Clark also wanted his students to succeed.

“To succeed in intelligence, you must have a lot of technical expertise to get you in, a specialty, whether it is political science or economics,” he said. “This community is a very large, imperfectly functioning network of people and organizations. Your strength and your ability to get things done is only as good as the strength of your network. You can’t be a recluse in the intelligence business and succeed. It doesn’t work. People have tried, but they didn’t get very far. Building a network gets you into places and gets you the information that you couldn’t get otherwise. Intelligence is really about acquiring and sharing knowledge and information – with an emphasis on sharing.”

Though he is stepping away from teaching, Clark continues to find ways to stretch his imagination and engage his brain. Three years ago, he took up the study of classical piano. “Though I’m not yet quite accomplished enough to perform one of Beethoven’s concertos, I can offer Debussy’s Clair de Lune and Wagner’s The Bridal March of Lohengrin.”

After adding an important chapter on Artificial Intelligence and its impact in the intelligence community to the eighth edition of his book this year, Clark also hopes to continue work on a humorous book on engineering feats through history.

“I subscribe to the adage, Don’t sweat the small stuff, and it’s all small stuff,” Clark said. “Just keep going. Keep doing what you do well. I would like to be thought of as someone who took advantage of all the things this country offered, who served my country well, and helped it along in some way. I am just happy, at this point, to say I did a lot of stuff, made a lot of mistakes, and helped to make a difference.”